It's not often that the team at ScreenAnarchy feels a loss like we have with David Lynch. And we're not alone; since last Thursday, I've seen an outpouring of love, sadness, and remembering that I've not seen the like of since David Bowie died. At least a few times a day, something about Lynch is passing through my social media feed. Lynch's features and many, many shorts, spread out across nearly 60 years, showcase such a unique mind, that his name has become shorthand for a particular narrative and style of film and story. Perhaps since ScreenAnarchy's main focus is on genre film, that we feeling the passing of this singular artist most keenly. So much so, that we've put together a reflection on his work. Our writers share their memories of Lynch's work, the effect it had on us, the range of his influence, and how we will carry and share his work in the future.

Dustin Chang, Ronald Glasbergen, Ard Vijn, Andrew Mack, Kurt Halfyard, Michele "Izzy" Galgana, Dave Canfield, Kyle Logan, Barbara Goslawski and Olga Artemyeva

contributed to this story.

Shelagh Rowan-Legg

I sometimes get strange looks when I tell people that Inland Empire is my favourite David Lynch film. I'm not sure I could even tell you why the last of his narrative features is closest to my heart, but maybe Lynch would want it that way, reluctant as he was to explain his work. I've always though it was less coherent than Mulholland Drive, in the best way possible. More completely disturbing in its mystery, showing not the glamour of Hollywood, but the inescapable psychological dissonance that happens to actors when they cannot separate themselves from their story. I watched it at least twice in cinemas, included it in a film course paper, and bought the disc as soon as one was available. I learned how to make quinoa from a short film Lynch had included. Somehow, Inland Empire felt right to this moment in Lynch's life, when he was circling back to his (arguably) most successful work with Twin Peaks: The Return.

I was in high school when Twin Peaks first aired, and part of the 'Who Killed Laura Palmer' generation who found something fascinating about Lynch's particular way of combining the everyday with the weird. No one else could do it like he could; even when one uses the adjective 'Lynchian', anything like that is merely an imitation. As others have noted, Lynch had a deep empathy that shows in his characters, and even the darkest and weirdest among them shows their very real scars. His films were partially lucid dreams, often nightmares, and ones that can never be explained in full, as one can never explain a dream in full. His influence is less in imitation, then, than in serving the weirdo inside you, however it might manifest. He understood that to be weird was normal, and any denial would drive you crazy. We owe him such thanks for sharing with us, his art of weirdness and empathy.

Dustin Chang

What I admired most of about David Lynch the filmmaker, was his ability to see beauty in darkness, without cynicism, in this often contrasting, dual world: light and darkness, good and evil, dreams and reality. Lynch played with this duality over and over throughout his filmography. Lynch's approach to his fears and nightmares, whether it be homeless people or that drugged up naked brunette who walked down the white suburban lane or seemingly normal family with dark secrets or an atomic bomb blast (all the flip side of American Dream), is to face them head-on, exorcising these negative thoughts out of his system on to the screen. They were frightening and mysterious. And they were all terrifyingly beautiful.

"We live inside a dream," Special Agent Dale Cooper says in Twin Peaks Season 3. To Lynch, dreams were as real and important as real life. That our lives, flesh and blood with its meaning of it all, may indeed be someone else's dreams. It's a humbling, yet comforting thought.

Thank you David, for all the terrifying, magnificent beauty. Sweet dreams.

Ronald Glasbergen

David Lynch 1946 -2025: Brilliant surrealist master of Suspense

Mulholland Drive (2001) is one of the most suspenseful films there is. Both the characters, the brilliantly played Betty / Diane by Naomi Watts and the fantastically ambivalent script and ditto direction by Lynch make it a masterpiece. As a painter in a time of film and photography, Lynch knew very well that ambivalence, multivalence, is the power of the image and that stories that can be expressed in more ways - textbook examples are classics such as Edgar Allen Poe's 'a dream within a dream'. And perhaps precisely because Lynch was so well aware of the stuff dreams are made or of the surreal side of our existence, he also occupied himself with transcendental meditation. In an interview, Lynch once described how a painting of a garden painted at night began to move before his eyes. That moment was one of the triggers for him to start experimenting with film. In his first four-year experiment, a number of short ones resulted in the inimitably fantastic feature Eraserhead (1977), which, together with his subsequent encounters with Mel Brooks and Dino de Laurentius, broke open his career. Followed, sometimes with long intervals, by a series of masterful alchemy of surrealism, suspense and ambivalence. Blue Velvet (1986), Lost Highway (1997), the TV series Twin Peaks (1991), Wild at Heart (1990), films that transcend their time entirely in the spirit of Lynch. With suspense as a by-product, he was the brilliant and unique, surrealist master of ambivalence: filmmaker, artist David Lynch, who died January 15, 2025.

Ard Vijn

My first exposure to David Lynch's work was The Elephant Man. After that it was Dune, a film I thoroughly enjoyed as I had just read the book and loved the epic look, warts and all. And that was basically it for ten years or so. I liked both films but they didn't register in my mind as having the same author's signature. Friends told me Blue Velvet was cool but I didn't see it then. So without expecting much I walked into a cinema in early 1991 to see Wild at Heart... and got my mind blown basically. This was what colouring outside of the lines looked like, while still making the image pretty. This was mood, atmosphere, condensed and poured into your eyes. There was shock and bafflement. And nothing in it was by mistake, I had no doubt I was fully seeing a vision just as the director had pictured it in his mind. Few people have ever had that power, that command of the trade. My admiration for David Lynch only grew when he hit me with the same hammer on a weekly basis, at home, during the airing of the first season of Twin Peaks. All I can say is thanks. Thanks for all the visions, thanks for the dreams, and thanks for the nightmares. And thanks for knowing that the tonal dial can be turned from 0 to 10 and back again, and thanks for using that whole range with precision and care. Thanks!

Andrew Mack

Not everyone gets their own adjective.

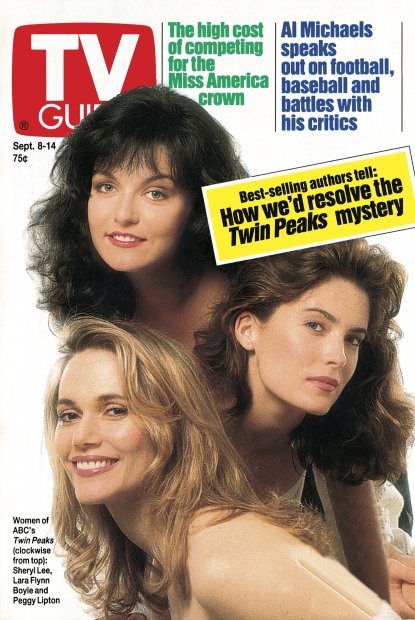

First, allow me to take on the role of historian or sociologist. You probably know this already because you read about it somewhere, but if you weren’t there you don’t truly understand: Twin Peaks was a touchstone moment in television. Its arrival created a seismic shift in network television in 1990. There was nothing like it on TV to that point. Everyone was watching it. Everyone! Even my rather conventional parents - known for engaging in anything fantastical only to entertain their son’s whimsy long enough to curtail his addiction - were hooked on it. Twin Peaks was everywhere. Everyone was talking about it, everyone wanted to know, “Who killed Laura Palmer?”. We hadn’t had a cultural movement like it since we asked, “Who shot J.R.?” ten years earlier.

Not everyone gets their own adjective.

Personally, for a filmmaker who became associated with all forms of artistic expression and creation, Lynch association with music is the other thing that sticks out for me as I sit here thinking about his body of work. To this day, I hear those first chords from Angelo Badalamenti's "Falling" and I am immediately transported to the town of Twin Peaks. Likewise, Chris Isaak’s song "Wicked Game", featured that same year in Lynch’s feature film, Wild at Heart, does the same thing to me. Lynch took songs and they transcended these fellow creators.

You say something is Lynchian and it immediately conjures up ideas, and expectations: surrealism, dreamscapes, menace and mystery. Though other directors may be known for their auteurism, few created art that deserved its own adjective.

David Lynch had his own adjective.

Kurt Halfyard

Bless the man who has the foresight to create his own eulogy 25 years before his passing.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, it seemed like a worthy project to walk my teenage girl through David Lynch’s entire filmography. She and her brother were deeply familiar with his 1984 take on Dune, the one project that the director disowned (in fact my preferred version of that film is the one directed by Alan Smithee, where Lynch had formally taken his name out of the credits due to animosity with the European television cut of the film, but also put him on track to demanding final cut for the rest of his career). Over the course of television, movies, short films, and even perfume adverts, it was interesting, like say The Beatles, or Roald Dahl, to see how easily an artist's work can cross two, or three, generations and connect, or more accurately resonate, immediately. Particularly his early 1990s cinema, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me and Wild at Heart.

Somehow, the one film we skipped was David Lynch’s 1999 The Straight Story, a funding collaboration between artsy Canal+ in France and Walt Disney, and a straightforward bit of kind Americana was sandwiched between the twin peaks of the director's grand puzzle-boxing nightmares, Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive. We took the opportunity to revisit it the other day, and boy howdy did it hit hard.

If you have not already rewatched The Straight Story after Lynch’s passing, you should do so. It is indeed a living self-Eulogy (along the lines of Robert Altman’s A Prairie Home Companion, or David Bowie’s "Lazarus" album). In a rated “G” package, the film carries a lot of Lynch’s humanistic themes around the intersection of dignity and anxiety, a welcome focus on the elderly (albeit, this threads across all of Lynch’s work in some fashion) and putting the simple aspects of life and living into a context that is well outside of the mundane. In Lynch’s words this is “the wonderful and the strange.” No matter how grim things get, an injection of a good, unselfconscious, dad joke (“What’s the number for 911?”) makes David Lynch, for all his eccentricities and esoteric meditations, and by all accounts (I never met him personally) a strange and wonderful human being with a gift of communicating this through his art. His loss is a major one to visual storytelling, but his legacy is mighty.

Michele "Izzy" Galgana

David Lynch wasn’t just an artist or a filmmaker. He was a shaman and an alchemist. Above all filmmakers, his work made me feel more deeply than anyone else’s and I am grateful to have been alive at the same time. His films are a lightning rod that zap and hiss and open into another, rarely seen plane of existence.

My entire feed on all social platforms was all about David Lynch the day after he died; this continued for days, interspersed with regular news, and it was incredibly beautiful to see how he and his work touched so many. I am thankful to have met him at a transcendental meditation event at Emerson College in Boston, about 20 years ago.

At the reception afterwards, I met him, we chatted briefly about acting, as I was still attempting to act then, before I became a full tilt filmmaker, and he kissed me on the cheek. Whatever he said about how he chose actors was obliterated by the presence of his lips on my skin. I’ll never forget that encounter or his playful, soothing presence. Good night to an absolute titan who shaped so many of us.

Dave Canfield

Postcard from The Black Lodge.

The impact David Lynch had on me took place over time. It started with a Siskel and Ebert review of Blue Velvet when I was 21. Though it planted a seed, it was planted deeply. It would be years until I saw the film. But even before that Lynch had gifted me with the knowledge that the world I saw around me wasn’t the whole story. There were dark things under the surface goodness so obvious it was easy to miss them. I have too many memories attached to his films to go through all of them here. But let me offer a few. My friend Kevin McCerney and I snowshoeing 1/4 of a mile through thigh-deep snow to a screening of Dune. We had called the theater on a lark to see if it was still open during the blizzard. They said they were contractually obligated to at least run it through the projector. We were the only ones in the entire theater. Im talking all the screens. I remember The Elephant Man finally leaping from the pages of my worn copy of Very Special People. He was even more alive in Lynch's camera. More beautiful. The part of me that felt I was so very different from others had discovered not so much a patron saint but a fellow traveller. Many years later, in Chicago, I and all the other local Chicago critics were seated in the Lake St. Screening Room to see The Straight Story. The screen lights up blue with the cheery white castle and star rainbow of the Disney logo only to go suddenly black as the phrase, “A Film by David Lynch” appears. Laughter all around at the irony. But of course this was the Lynch-iest of ironies. The pure innocence of an old man’s quirky attempt at reconciliation with his estranged brother conjured by the same heart that had created the warped Frank Booth of Blue Velvet. A character of criminal ravings and cravings for nitrous oxide and sexual violence. But in Lynch's capable hands even Booth took on a humanity that seemed utterly plausible.

I discovered Twin Peaks via a set of worn VHS tapes that had been endlessly passed around by friends. After that I was never the same. It was less a television series to me than a resonant portal where good and evil finally took on their true significance refusing to be mitigated by the mundane. If real life too often resembled a soap opera, then Twin Peaks was the reminder that however tawdry and cartoonish the situations became, life was still a dangerous and beautiful business populated by beings inherently transcendent. I remember weeping several times as the melodramatic waves washed over me carrying assurance, saying that it was possible to be washed clean even when lost in the deep darkness.

But much of Lynch’s work took place in that darkness. Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive both mocked the superficiality viewers often bring to cinema. Viewers often want to believe their lives can be like a movie. But the movie gods don’t care about your hopes or dreams and the main characters in those films learn a terrifying lesson. If you aren’t careful you get trapped within yourself wandering between illusions and all too real torment. Watching those movies was like holding a phantom hand determined to drag you through hell. Who knew that was the way to self-recognition.

And Lynch, most definitely recognized himself. I haven’t mentioned Eraserhead yet. Lynch reportedly made the film at least in part, as a response to his daughter Jennifer being born with severely clubbed feet. Eraserhead seems to take place in exactly the sort of universe where such random cruelties would be de rigueur. But it was never the case for Lynch that the darkness could exist without the light. People have argued about the ending of Eraserhead ever since Henry, a cinematic surrogate for Lynch himself found a warm embrace at the end of much suffering. Perhaps this accounted for the enigma of Lynch's true identity.

Kyle Logan

I saw my first David Lynch film when I was 14. It was Mulholland Drive and as a born and raised LA kid, I felt an immediate connection with it without really knowing what to make of it. I did know that I loved Linda Scott’s “Every Little Star” though, I played a youtube video of it on repeat for days if not weeks after first seeing the movie.

A few weeks later, I rented Blue Velvet and prepared myself for another strange and alluring film. I had to turn it off during what we’ll call “the ‘mommy’ scene.” I’d seen and loved Alien and 28 Days Later and thought I could handle anything. Lynch showed me I could not. Years later I saw Blue Velvet in full in a theater and it’s now one of my favorite films.

I wouldn’t call him my favorite filmmaker anymore (I certainly did at one point in my early 20s), but I will never forget how he invited me into his strange world(s) and reminded me that I was still a child within weeks of each other.

Thank you David, for all the magic and horror you brought into my life. I wouldn’t be who I am without you.

Barbara Goslawski

David Lynch turned me into an avowed voyeur. I was growing up in a cinematic universe where predictable storylines, and an inordinate focus on characters and performances dominated my cultural landscape. Let’s face it, besides the occasional block buster, I was watching filmed theatre (Woody Allen movies spring to mind). One night, my goofy friends and I drunkenly stumbled into a midnight screening of Eraserhead and that’s when everything changed. I didn’t know what to make of what I saw but I did know that David Lynch was transforming my very way of seeing.

Lynch’s brand of surrealism was captivating – it was strange but also so freakishly familiar. He imbued even the most ordinary situations with a dreamlike quality, often when you were least expecting it. He teetered so enticingly on the brink of nightmare. Despite thematic appearances, his vision was the stuff of everyday life: it just happened to contain realities that no one wanted to face. No matter the genre, this director’s goal was to show how innocence didn’t stand a chance in the world, whether it be in The Elephant Man or Twin Peaks. Blue Velvet stuck with people not only for its disturbing logic but also since Lynch went back into the noir genre to push themes, characters and even the most disturbing hidden outcomes into their ugliest most inevitable conclusions. All this to actually showcase a human frailty, a fallibility, that one could not ignore. David Lynch proved to me that there are more ways than one to be decidedly humanist.

Olga Artemyeva

I have only seen David Lynch once, but in a red room of all places. At the Rome Film Festival in 2017 he was being given a lifetime achievement award and was holding a masterclass which I went to. Lynch was sitting in the middle of all the red, on a red chair, in front of a red table, and was speaking in his trademark style. He told anecdotes about David Bowie and Harry Dean Stanton (he was apparently hilarious). On the topic of Stanton, someone asked if Lynch too would like to work in his nineties. Lynch said he'd like to work in his hundreds... The best question of the hour came when someone got up and asked: How do you pull yourself out of all this shit? Lynch obviously answered that he does that with the help of transcendental meditation, and spent another fifteen minutes talking about it. Well, as far as we're all concerted, we had Lynch for precisely that purpose. It's clear we all exist in his world, some variation of Twin Peaks where the border between the so-called reality and the Black Lodge has worn thin. Up until the last week, in this bizarre reality we still had David Lynch with us. Someone who created chaos while simultaneously being able to regulate it, who invented the language to try and explain the things that aren't meant to be explained. Most importantly, he was someone who had this unwavering belief that you can if not defeat the darkness, then at least leave it for something else. The loss of this strangely and also inexplicably optimistic worldview is honestly the scariest part. According to transcendental meditation practices and Lynch's own art, he simply changed his form for something else, but what remains unclear is what we are now supposed to do to pull ourselves out of all this shit.

More about Eraserhead

More about The Elephant Man

More about Dune (1984)

More about Blue Velvet

More about Fire Walk With Me

More about Wild At Heart

More about Mulholland Dr.

Around the Internet

Recent Posts

Leading Voices in Global Cinema

- Peter Martin, Dallas, Texas

- Managing Editor

- Andrew Mack, Toronto, Canada

- Editor, News

- Ard Vijn, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Editor, Europe

- Benjamin Umstead, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, U.S.

- J Hurtado, Dallas, Texas

- Editor, U.S.

- James Marsh, Hong Kong, China

- Editor, Asia

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana, New England

- Editor, U.S.

- Ryland Aldrich, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, Festivals

- Shelagh Rowan-Legg

- Editor, Canada