Another year of movie-watching is over. 2019 was pretty special for me for several reasons. First of all, I was selected to be part of Fantastic Fest 2019 Screening Team, so I had to review over 60 film submissions. That was a pretty cool experience and I look forward to be more involved in film programming in the near future.

Then, in May, I attended for the first time ever the Cannes Film Festival, where I was lucky enough to get a ticket for the world premiere of Bong Joon-ho's Parasite (the eventual Palme D’or winner) at the Palais. I didn’t carry a damn tuxedo to Cannes in vain because that screening was amazing: picture, for example, the entire Palais cheering when Song Kang-ho's character shows a tissue with blood (we know it’s actually ketchup) to finish his family’s master plan!

I will remember 2019 precisely as the year in which three of my all-time favorite filmmakers released true masterpieces. Aside of Parasite –now a total commercial success, even in Mexico as the film opened here on Christmas Day and I just witnessed last weekend a sold-out screening at a Cinépolis complex (the antithesis of an arthouse cinema)–, I loved The Irishman, master Martin Scorsese’s epic goodbye to the gangster movie. The legendary Robert De Niro himself visited Mexico, so that whole evening at the Los Cabos International Film Festival (which has become my favorite national festival) was very memorable.

Then, Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, my top film of the year. Like Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino is a hero of mine and I think he has never made a film that’s not great; however, Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is easily his best in 10 years, already up there with the likes of Pulp Fiction, Reservoir Dogs and Inglourious Basterds. The number of times I watched it on the big screen (including the stunning 35mm and 70mm versions) is embarrassing, but hey, like any Tarantino film, it just gets better and better with each viewing.

Ultimately, I was able to break my personal record and watch 172 new releases in 2019. As usual, my full list of favorites, which you can find in the below gallery, features some 2018 films that were released in Mexico until 2019, but also some titles from the festival circuit that will hit theaters and/or streaming platforms in 2020.

Eric Ortiz's favorite movies of 2019...

Special mention:

WRINKLES THE CLOWN by Michael Beach Nichols

As part of Fantastic Fest 2019 Screening Team, I supported a handful of titles, and in the end only Wrinkles the Clown made the cut (I was warned since the beginning, by esteemed FF programmer Logan Taylor, that the process was harsh). So yeah, can’t help to feel a special connection with this documentary; that said, it’s really fascinating. This is what I wrote back then:

I didn’t know anything about Wrinkles the Clown, so this documentary worked for me just as the filmmakers intended. That is because it has a huge plot twist near the ending that changes everything and turns a mildly interesting documentary about an old man who gets hired to dress as a clown and scare children, into a fascinating examination on Internet phenomena. The director fools you with the perfect structure for an exercise accordingly the Wrinkles the Clown phenomenon. Scary clowns, viral Internet videos and a dose of Banksy’s Exit Through the Gift Shop, this film is very surprising.

Honorable mentions:

25. JOHN WICK: CHAPTER 3 - PARABELLUM by Chad Stahelski

24. THE GASOLINE THIEVES by Edgar Nito (my full review here) / THE GUARDIAN OF MEMORY by Marcela Arteaga

23. HAIL SATAN? by Penny Lane

22. COLOR OUT OF SPACE by Richard Stanley (my Fantastic Fest review in Spanish here)

21. PETTA by Karthik Subbaraj

Honorable mentions:

20. THE GOLDEN GLOVE by Fatih Akin

19. JALLIKATTU by Lijo Jose Pellissery

18. JOJO RABBIT by Taika Waititi (my full review from Los Cabos here)

17. MARRIAGE STORY by Noah Baumbach (my Los Cabos review in Spanish here)

16. JOKER by Todd Phillips

15. PAIN AND GLORY by Pedro Almodóvar

It’s easy to deduce that Antonio Banderas’ character in Pain and Glory (Salvador, a film director who hasn’t been able to shoot a movie in quite some time due to his physical and mental pains) is a cinematic version of Pedro Almodóvar himself. The Spanish filmmaker evokes a series of memories from his own life (including his childhood, his first sexual desire, a truncated yet unforgettable love, and his relationship with his mother) in an exercise that also reveals his love for cinema and the artistic process. The fascinating “autofiction” Pain and Glory might be Almodóvar’s most personal film, with the director, in an emotive way, facing his mother’s death and his regrets as a son, and exposing how much it means for him to express himself and heal through cinema.

My Cannes review in Spanish here.

14. DOGS DON’T WEAR PANTS by J.-P. Valkeapää

I watched this Finnish film one morning at the Cannes Film Festival without knowing anything about it, so it was a genuine discovery. Dogs Don’t Wear Pants tackles the mourning of Juha (Pekka Strang), a surgeon who lost his wife. Many years after the tragedy that turn him into a single father –and now that his daughter (Ilona Huhta) has grown up– he can’t move on with his life. Later on, Juha meets by chance Mona (Krista Kosonen), the dominatrix at a sadomasochistic establishment. They begin a secret relationship, however we understand that Juha is not there to obtain sexual pleasure, moreover he’s trying to to get someone else to end with his own life. While all of this indicates Dogs Don’t Wear Pants is a depressing European drama, what follows is closer to Asian cinema. Not only because some scenes are quite explicit, but also because the director goes for dark humor and a true love story based on a couple of twisted souls and their sadomasochistic interests. Outside of what is considered normal, one can still find a real and even hopeful connection that can lead to healing.

My full Cannes piece in Spanish here.

13. MIDSOMMAR by Ari Aster

Midsommar is a continuation of the way in which Ari Aster has approached the horror genre. It takes even less time than in Hereditary to explore a clichéd scenario: the young American students who, guided by a European friend, travel to that continent (in this case to a Swedish commune). But this ain't Hostel, as Aster deals with a subgenre known as folk horror, of which one of its main exponents is the unforgettable British film The Wicker Man. Aster follows the path of The Wicker Man once the Americans enter a pagan commune that continues to practice their ancestral rituals, apart from modernity and what we consider normal. The valuable thing about Midsommar is that, equivalent to what he did in Hereditary, Aster manages to provide his own voice. It’s vital that the problems of the main couple, Dani (Florence Pugh) and her asshole boyfriend Christian (Jack Reynor), are at the core of the film. There are many other unique elements that separate it from The Wicker Man, be it the cinematography’s dazzling brightness (everything happens during the day), the wicked sense of humor or the immersive exercise with POV shots that emphasize the characters’ altered states. Midsommar is continuously disconcerting, a bad trip that always leads us towards a ritual that may be part of the beliefs of a commune, but that’s still terrifying and twisted.

12. DEERSKIN by Quentin Dupieux

Georges (played brilliantly by Jean Dujardin), a man recently separated from his wife, pays a good amount of money for a deerskin jacket and immediately becomes obsessed with the garment. Since the old man who sold him the jacket decided to give him a video camera (in one of those random actions so characteristic in Quentin Dupieux’s cinema), Georges will invent that he works as a filmmaker when he begins to socialize with bartender Denise (Adèle Haenel). Naturally, in Dupieux's hands, both gags that involve the protagonist –the jacket and the lie that he's a film director– will reach the last consequences of the absurd, with Dupieux mocking low-budget filmmaking and, of course, his own figure. Deerskin evolves into something that could be considered part of the slasher subgenre but, unlike Rubber (Dupieux’s film about a killer tire), it also offers us the humorous version of the serial killer movies that are closer to psychological horror. Laughs never stop in this strange cocktail about a filmmaker and serial killer (really), motivated by an unattainable dream that he shares with his beautiful deerskin jacket (!) and financed by a young woman with the caliber of film producer. Undoubtedly, one of the best comedies of 2019.

You can read my Fantastic Fest review in Spanish here.

11. THE GUILTY by Gustav Möller

I missed Gustav Möller’s debut feature-length film, The Guilty, at Fantastic Fest 2018 but luckily, and surprisingly, it got a theatrical release in Mexico in early 2019. Much like Joel Schumacher’s Phone Booth (which was written by the late, great Larry Cohen) and Steven Knight’s Locke, The Guilty proves that a minimalist premise (a man talks on the phone) can lead to an intense thriller and a complex humane drama/character study that happens in “real time.” By observing the protagonist Asger (an incredible performance by Jakob Cedergren) while he does his job as an emergency number operator in Copenhagen, Denmark, and just with a couple of locations (both in the same building), The Guilty becomes a terrific police thriller and a character study with a potent plot twist that opens a reflection on the dangers of the (apparent) justice delivery and that forces the protagonist to face his own actions and assume the consequences.

10. HORROR NOIRE: A HISTORY OF BLACK HORROR by Xavier Burgin / SESIÓN SALVAJE by Paco Limón and Julio Cesar Sánchez

I just love documentaries about cinema that end up costing you money, meaning that when they're over you have discovered many new movies and you can’t wait to track them.

Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror is a poignant documentary that invites us to know the perspective of African-Americans towards horror films. Analyzing both the problems (from invisibility, problematic representation, to the countless tropes) and the moments that positively changed the course of history (from Night of the Living Dead, Blacula, Tales from the Hood to Get Out), in addition to highlighting lesser-known films (Ganja & Hess, Eve's Bayou or Bones); Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror basically makes us understand the importance of fair representation in a massive medium, undoubtedly powerful as cinema.

You can read my interview with co-writer and producer Ashlee Blackwell here.

On the other hand, Sesión salvaje, which was part of last year’s Mórbido Fest, is Spain’s answer to the work of Mark Hartley (Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation!, Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films), as it’s a highly entertaining celebration of the wildest Spanish cinema from a bygone era. Long before Álex de la Iglesia and subsequent genre directors like Jaume Balagueró, Paco Plaza, Nacho Vigalondo and J.A. Bayona, there were westerns, horror movies, cinematic violence, sex comedies, social thrillers, exploitation efforts, and in general Spanish cinema that just couldn’t be made today. A much-deserved homage that will make you dig into the work of such filmmakers as Narciso Ibáñez Serrador (Who Can Kill a Child?, The House That Screamed), Juan Piquer Simón (Pieces), Joaquín Romero Marchent (Cut-Throats Nine), Eloy de la Iglesia (Cannibal Man) and Iván Zulueta (Rapture).

9. FIRST LOVE by Miike Takashi

Few directors can turn explicit violence into something completely enjoyable and fun, but Miike Takashi is, of course, a master of this art. First Love, which marks his return to yakuza cinema, is a wild cocktail (with a young boxing promise circumstantially involved with the crime underworld) that proves Miike, at 59, is still surprising at his unpredictable way of innovating. It’s one of those films that constantly make you wonder: how in the hell did someone come up with that? A thought always related to the high level of violence but also to comicalness, exaggeration and the absurd. On top of that, and like its title indicates, First Love is another example of humanity as an essential part of Miike’s cinema: here, all that craziness already mentioned comes together with a love story and a couple of endearing protagonists (the boxer and a young girl trapped in the world of yakuzas and drugs), whom you want to see together at the end of the madness. A high point in Miike’s prolific filmography.

My Cannes review in Spanish here.

8. THE MULE by Clint Eastwood

The Mule, Clint Eastwood’s best film since Gran Torino, is based on a complete juxtaposition: a 90-year-old war veteran (Eastwood’s first acting role since 2012 –and perhaps last one ever– is unforgettable), who has dedicated his life to horticulture, gets unexpectedly involved with drug trafficking, working as a mule for a Mexican cartel. With echoes of Gran Torino, Breaking Bad and The Wire, The Mule works as a crime film, it’s funny (charismatic and old-fashioned Clint vs. millennials!) and also touches such important subjects as racism in the U.S. and the forgetfulness of seniors even if they are war veterans; but most importantly, it’s a very humane and emotive portrait of an old man seeking for redemption. A real shame Eastwood is now seen as a villain in the media because he concluded the decade with really strong work. Hell, I have seen already the first great 2020 release (Richard Jewell opened in Mexico on New Year’s Day) and it was directed by Eastwood as well!

My full review in Spanish here.

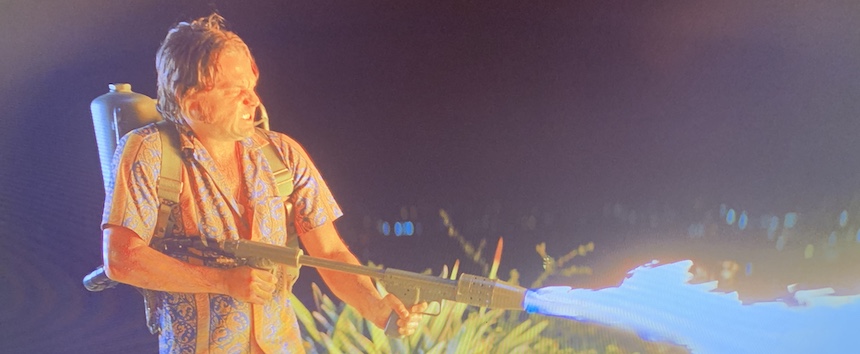

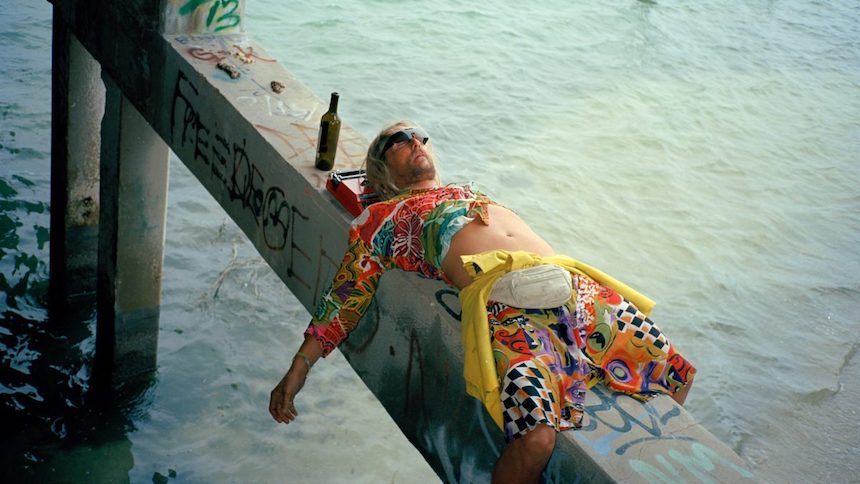

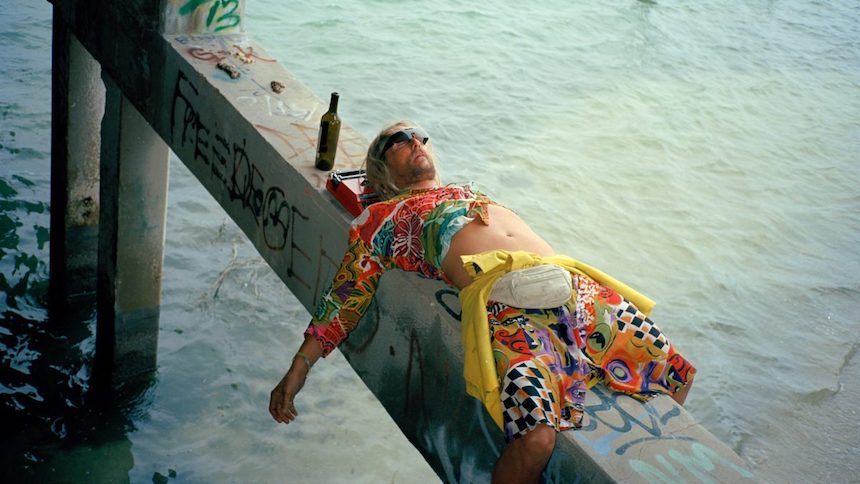

7. THE BEACH BUM by Harmony Korine

Some movies give you the sensation that everyone involved were just having an amazing, crazy time during the shooting. Harmony Korine’s The Beach Bum is one of those, with an inspired Matthew McConaughey as the free, childlike and irresponsible spirit that is the memorable poet and pothead Moondog. I get why The Beach Bum is not for everybody: it’s comedy at its most absurd, it features bigger joints than those from Cheech and Chong flicks, a marijuana tree courtesy of Mr. Snoop Dogg, the most brilliantly overacted facet of Jonah Hill, several sexual jokes, and so forth. Let me put it this way, when Mexican director and fellow cinephile Isaac Ezbán commented that he didn’t like it at all because he couldn’t believe anything of what happened, I just said to him: I can’t believe you haven’t been on a small plane with a pilot that’s blind and uses weed and cocaine to see! As you can tell, I laughed my ass off watching The Beach Bum, an absurdist masterpiece.

6. KNIFE + HEART by Yann Gonzalez

I love Knife + Heart because it does bring freshness and craziness to the giallo, right from its start when the masked killer uses a dildo knife to brutally murder a young gay man. I love it as a period piece, shoot on film, that takes us to the world of gay pornography in Paris during the late seventies; it’s one of the funniest movies about movies in recent memory, due to the fact that it shows the making of Homocidal, the parodic porno version of the giallo-like murder mystery (even with Mexico’s Noé Hernández just having a blast as one of the actors). And I also love that at its core there are two tragic love stories, one involving Vanessa Paradis’ character (the leader of the small and charismatic film crew that has become the killer's target) and the woman she longs for; and the other being part of the murderer's brutal background that deals with homophobia. In Yann Gonzalez’s unique second feature, it all comes together in a beautifully weird way.

5. DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE by S. Craig Zahler

What the hell is it with all the think pieces against writer/director S. Craig Zahler? Dragged Across Concrete was supposed to be, according to Twitter and the media, a racist film, a dream for the alt-right. It’s great that at the beginning Zahler kind of mocks all of this, as the film does seems to be taking that road, through Mel Gibson’s character Brett, no less: he gets suspended for police brutality and is tired of living in a not-so-pretty neighborhood where his daughter has been assaulted by some African-American youngsters. But this isn’t a vigilante film at all, it doesn't even follow a Death Wish-type scenario. It’s actually in part a hangout movie that follows Brett and his partner Anthony (Vince Vaughn) prior a heist. With credible character motivations, Zahler even takes time to build the background of the minor characters and the film also has a magnificent western vibe during its climax. The three main actors, Gibson, Vaughn (their interaction is quite memorable), and Tory Kittles, are all fantastic. Zahler has a small but perfect filmography and Dragged Across Concrete is, in my book, his finest film so far; and certainly that’s saying a lot considering that his previous efforts were Bone Tomahawk and Brawl in Cell Block 99.

4. DOLEMITE IS MY NAME by Craig Brewer

The biopic about Rudy Ray Moore (Eddie Murphy’s return to greatness) joins the tradition of movies about passionate film workers who, against all odds, made their dreams come true. Dolemite Is My Name is a colorful and hilarious look at the making of Dolemite, the blaxploitation classic about the titular charismatic pimp/raconteur/showman who goes out of prison and reencounters with his criminal rival. With a truly terrific cast (Da’Vine Joy Randolph, Keegan-Michael Key, Wesley Snipes, Craig Robinson and Tituss Burgess, among others), Dolemite Is My Name feels close to Ed Wood (it was also written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski) and The Disaster Artist, but it also reminded me of Baadasssss!, the biopic about another important blaxploitation figure (Melvin Van Peebles) and his key film: Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Both Melvin Van Peebles and Rudy Ray Moore defied the system, acting as true guerrilla filmmakers, and their movies were made successful by an audience that felt identified with them. Dolemite Is My Name is a satisfying and much-needed reminder that movies are only relevant if they connect with an audience. A great celebration of popular cinema that overcame bad reviews, and of an artist, Rudy Ray Moore, who wanted to give people nothing but a show that was worth the admission price.

My full piece in Spanish here.

3. PARASITE by Bong Joon-ho

After two international productions with A-list actors, Snowpiercer and Okja (both eloquent metaphors of the state of the world), master Bong Joon-ho returned to South Korea, and to his preferred actor Song Kang-ho, to explore once more social inequality. Parasite continues Bong’s trademark of perfectly mixing different tones and balancing drama, comedy and multidimensional characters. On one hand there’s the poor family, charismatic, for which we feel empathy, but their actions end up being morally (very) wrong. And on the other, the rich family (Lee Sun-kyun and Cho Yeo-jeong play the parents), naive and yet ready to look down on those who smell different (the poor family’s smell is distinctive and associated to their marginalized place where they live: a sub-basement). More than delivering a straightforward class war, Bong never stops surprising us with Parasite, arguably his best film since Mother; hilarious, brutal, bittersweet and always complex.

My review in Spanish here.

2. THE IRISHMAN by Martin Scorsese

Martin Scorsese's epic film of remembrance, with which he returns to the gangster cinema and to several of his favorite actors: Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Harvey Keitel in particular, not to mention that another icon of this type of cinema, Al Pacino, debuts in the filmography of the Italian-American director. Scorsese is a master who makes each sequence, each montage, in his three-and-a-half hour epic, memorable. There’s a monumental cinematic richness, rhythm changes, stylistic details, archival material to contextualize the actions and make references to historical moments, and even some winks at the gangster genre classics and at Scorsese's own work. But beyond everything, at the core of The Irishman lies a master class of acting, confirming what was said by a Scorsese disciple, Paul Thomas Anderson: “The best special effect you can have is a great actor. A great actor beats a fucking spaceship, any day." The Irishman is a film that reaches the last consequences of a criminal life. No matter if your name is Jimmy Hoffa (Pacino), Russell Bufalino (Pesci) or Frank Sheeran (De Niro), all wise guys end up dead or if they manage to grow old, the brutal passage of time may lead them to an even more painful destiny (either inside jail or being "free" again): remorse, attempted redemption, natural deterioration, loneliness and total oblivion. I hope that the great Scorsese continues to make films, but for the moment The Irishman feels like his powerful and brilliant farewell, definitive at least to the gangster cinema and the wonderful actors that accompanied him in this genre for several decades.

My full review from Los Cabos here and I also got to interview producer Gastón Pavlovich.

1. ONCE UPON A TIME… IN HOLLYWOOD by Quentin Tarantino

Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is Quentin Tarantino’s ultimate homage to cinema (and television) and all of its soldiers. It’s Tarantino giving free rein to his passion, recreating a western show from a bygone era, creating a whole mythology about his main character, actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio at his finest), referencing Sergio Corbucci and The Great Escape, and so forth. It’s a colorful and peculiar hangout movie, we get to spend time with Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie, subtle and emotive) at the movies enjoying her own performance in The Wrecking Crew, and with stuntman Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt’s most memorable performance since Inglourious Basterds) while he drives through Los Angeles or feeds his dog. It works as a buddy movie too: Rick and Cliff are a memorable and hilarious duo, with a good part of the emotional core of the film based on their friendship. And it’s also one of Tarantino’s most humane works (with Dalton dealing with the end of an era, for example), one that comes just after a complicated time for the filmmaker. Tarantino evokes the historical revisionism of Inglourious Basterds and, at the same time, deals with the controversy that has followed him since Reservoir Dogs, product of the most scandalous essence of his cinema: the kind of explicit violence that only provokes absolute joy and satisfaction (watching Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood at a packed theater was one of those experiences that revived the magic of the big screen). At a time when critics with supposed progressive thinking keep on questioning him, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the Manson family members in the film denigrate the work of actors, because –to paraphrase them– while they pretend to kill for entertainment, real people are dying in Vietnam, or because while they enjoy their money and live in Hollywood mansions, their negative and violent influence has imbued society. But in spite of this, Tarantino remains faithful to himself and to his cinema: for him, actors are nothing but heroes that can change everything, even a fateful story in Cielo Drive, at least while the theater remains dark and the fairy tales are projected.

My complete take in Spanish here.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights?

Click here to report it, or see our

DMCA policy.