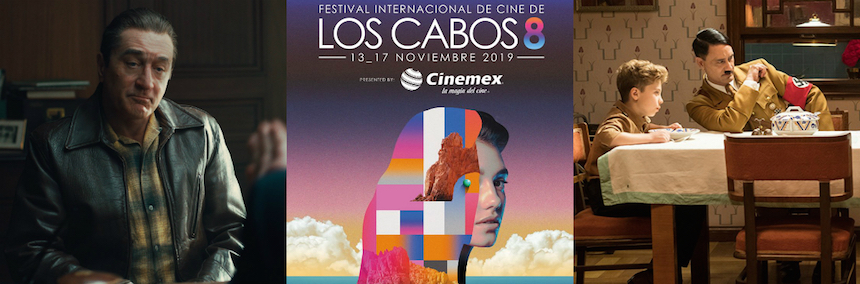

The Irishman by Martin Scorsese

In a nursing home, Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran (Robert De Niro in one of his greatest performances) becomes the classic Martin Scorsese-style narrator, protagonist of an epic film of remembrance, with which Scorsese returns to the gangster cinema and to several of his favorite actors. In addition to De Niro, we have Joe Pesci and Harvey Keitel, not to mention that another icon of this type of cinema, Al Pacino (Michael Corleone and Tony Montana himself), debuts in the filmography of the Italian-American director. The Irishman, faithful film adaptation of Charles Brandt’s book I Heard You Paint Houses, follows a tradition and has Scorsese’s signature, although it also explores other territories, contexts and a very particular life story.

Frank Sheeran wasn’t like Henry Hill (Ray Liotta’s character in Goodfellas) who always wanted to be a gangster. In fact, one of his first comments as part of the narration in The Irishman refers to his initial ignorance about the gangster world, in which the phrase "paint a house” actually means to shed blood mercilessly and strictly for business. While Sheeran knew about violence and brutality (he had fought hard in World War II), his rise in organized crime took place gradually, from his involvement with the Teamsters truckers union in Philadelphia and his eventual relationships with such characters as "Skinny Razor" (played by one of Scorsese's contemporary regulars: Bobby Cannavale) –to whom he sells the meat he stoled at his union work–, Bill Bufalino (Ray Romano as the Teamsters' lawyer, skillful to help thieves get away with it), Angelo Bruno (Keitel, of brief but notable participation as the leading mobster in that city) and Russell Bufalino (Pesci, in his superb return, gives life to this eminent criminal boss). Sheeran, a working-class family man, will enter that world where illegal activities are an everyday norm, soon finding himself at a point of no return.

Respecting the essence of I Heard You Paint Houses (interestingly, the title of the book is the one that appears on the screen at the beginning), The Irishman is told from the perspective of an old Sheeran, who remembers his life for the audience. While we see his development in the field of criminals of Italian origin, we constantly return to a summit chapter, chronologically subsequent, which mainly serves to delve into the bond between Frank and Russell. Part of the peculiarity of a protagonist like "The Irishman" is precisely that he never ceased to be an outsider, "adopted" by the powerful but subtle Russell, his first father figure with whom he didn't have a blood kinship. The reunion between De Niro and Pesci in a Scorsese film (something that hadn’t happened since Casino in 1995) takes place while the mature Sheeran and Bufalino, together with their respective wives, share a road trip in the seventies, towards a wedding in Detroit. Also this trip serves as a remembrance for the characters, who suddenly go through the place where they met and so the story of Sheeran's life really begins, many years before the trip to Detroit, thanks to the much publicized de-aging technology.

In terms of these special effects, which took a long time to rejuvenate the actors and which undoubtedly mean a risky decision, it must be said that they are slightly disconcerting at first instance. You can notice the digitalization, but it's only a matter of time so that, as spectators, we “get used to it” and appreciate the effects because they don't really distract us from storytelling and, on the contrary, enrich it. Thus, Scorsese manages to take us to Sheeran's life from the time he was a young man during World War II until his decline in the aforementioned nursing home.

Scorsese is a master who makes each sequence, each montage, in his three-and-a-half hour epic, memorable. There’s a monumental cinematic richness, rhythm changes (from agile montages to almost static long sequences where everything depends on the performances and dialogues), stylistic details (for example, those letters on the screen to let us know about the fatal destiny of practically all criminals in question, and certainly a great musical selection), archival material to contextualize the actions and make references to historical moments such as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the Cold War, the murder of John F. Kennedy (his brother Robert, by the way, was one of the great adversaries of the mafia, especially during JFK’s term) and the Watergate scandal, and even some winks at the gangster genre classics (certain planning of a murder in a restaurant recalls Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather) and at Scorsese's own work (it's inevitable not to think about Travis Bickle and Taxi Driver when watching Sheeran choosing guns for this murder).

But beyond everything, at the core of The Irishman lies a master class of acting, mainly thanks to De Niro, Pesci and Pacino, the latter as the explosive, egocentric and charismatic Jimmy Hoffa, president of the Teamsters union, ally (although an eventual threat) to the mafia's interests, and Sheeran's second father figure. Some secondary actors are not far behind, particularly Stephen Graham (Snatch, This Is England) with what is probably his best performance so far, as “Tony Pro”, another important gangster and unionist but, at the same time, disrespectful (he wears shorts for a meeting with Hoffa!), arrogant and uncontrollable. The type of character that once would have been perfect for Pesci, who for his part now gives us his most measured and –even being a mafia boss– humane interpretation.

It is each of the interactions between these brilliant actors what makes The Irishman one of Scorsese's great works, with all that characteristic color (a delight those culinary details, for example when the mobsters soak their bread in wine, hide their alcohol in watermelons, or the emphasis on Hoffa's taste for ice cream), humor and an apparent simplicity (as I mentioned, various sequences rely entirely on the actors) but confirming what was said by a Scorsese disciple, Paul Thomas Anderson: “The best special effect you can have is a great actor. A great actor beats a fucking spaceship, any day” (Anderson said this in a talk with Quentin Tarantino about The Hateful Eight). Although the Marvel generation may think otherwise, without a doubt Sheeran (De Niro) and Bufalino (Pesci) eating bread soaked in wine, Sheeran and Hoffa (Pacino) discussing business in pajamas before sleep, or the heated fights between Hoffa and “Tony Pro” (Graham) beat any pyrotechnic show of special effects.

Naturally, most of these interactions only deepen the special connection that over the years Sheeran built with his two father figures. Also, a key character in The Irishman is Peggy, one of Sheeran's four daughters, who is played by Anna Paquin and, when she's still a child, by Lucy Gallina. Comparing the film with the book, this is perhaps the greatest contribution of Scorsese and screenwriter Steven Zaillian: at times The Irishman is seen from the perspective of Peggy, how she witnessed since childhood her father’s roughness and realized, little by little, who he really was. In fact, the different kind of relationship Peggy always had with his father's mentors, Bufalino and Hoffa, also represents the crucial dramatic part of The Irishman. Peggy feared both his dad and Bufalino, but she looked up to Hoffa – a representation of how we all come to think that criminals act in a certain way, but sometimes we don't realize that the biggest criminals, the ones who truly pull the strings, are those who claim to advocate for the workers' rights, those charismatic politicians such as union leader Jimmy Hoffa, whose monetary loans supplied the great bosses of the time and who didn’t avoid spending time in “college” (prison). In The Irishman, the wars between gangsters and the conflicts among union members go hand in hand, provoking that the chapter about the trip to the wedding is actually part of the climax that will see the two “fathers" of Sheeran in conflict and, consequently, the protagonist facing another crucial moment in his life. Pure cinematic drama.

Family and friendship have always been relevant themes in gangster cinema. In this vein, The Irishman is a film that reaches the last consequences of a criminal life. Peggy is essential to the human aspect of this epic reflection. She remained silent, maybe asked some questions but she didn’t get, obviously, honest answers. However, his silence, eventually definitive (as an adult she never spoke to her father again after Hoffa’s disappearance), symbolizes that negative destiny that a family man is inevitably heading to once he decides to “break bad”, doing the "dirty work" and "painting houses" (these murder scenes, by the way, are not at all scandalous, but rather brutally cold). No matter if your name is Jimmy Hoffa, Russell Bufalino or Frank Sheeran, all wise guys end up dead or if they manage to grow old, the brutal passage of time may lead them to an even more painful destiny (either inside jail or being "free" again): remorse, attempted redemption, natural deterioration, loneliness and total oblivion.

I hope that the great Martin Scorsese continues to make films, but for the moment The Irishman feels like his powerful and brilliant farewell, definitive at least to the gangster cinema and the wonderful actors that accompanied him in this genre for several decades.