10+ Years Later: PONTYPOOL Is The Canadian Quarantine Movie To Fuck With Our Current Headspace

“In our top story of today, a big, cold, dull, dark, white, empty, never-ending blow my brains out, seasonal affective disorder freaking kill-me-now weather front, that'll last all day.”

Grant Mazzy, a big city talk-radio host, who has been down on his luck as we meet him, demoted to community radio in rural Ontario, attempts to articulate the feeling of anxiety in the moment before something is about to happen. “But then,” he adds, “Something is always about to happen.”

It may be spring, but at the exact moment of me writing this, there is a snow squall outside my window, and figuratively, whever you are, our collective pandemic shut-in experience is an ongoing, churning white-out of depression and anxiety.

This makes Bruce McDonald’s radio-play-cum-cult-film as relevant now, as it was fascinating then. Pontypool positions an infectious outbreak of disease, violence, and social-disorder, outside of direct observation of the above it all, privileged, smart-ass anti-hero of the film, and by proxy, us, the viewer. Oh, yea, it is also a hell of a Valentine’s Day movie, being set on February 14th. There are not many of those really. If Die Hard, The Long Kiss Goodnight, or Eyes Wide Shut can be regularly mentioned as counter-viewing Christmas movies, then Pontypool has a curious lock on The Hallmark Holiday, of sweet whispers, and the secret language of lovers.

Remember boys and girls (or boys and boys, or girls and girls): “Kill is kiss.”

*Warning: spoilers below.*

Back in 2008, Pontypool took the omnipresent zombie sub-genre, which was given new life in 2002 from Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later… and dose of meta-self-awareness with Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Dead shortly thereafter, and infused it with a dry, Canadian, subversive wit. In good zombie tradition, maximized its minimal budget with a single location and a clever conceit. That is to say, that the infection spreads here, in the form of language, ideas, and the understanding of the two as they come together in the brain. The zombies in Pontypool, referred in the end-credits as, ‘conversationalists’ (how very Canadian), attack as a mob, spouting tape-loop gibberish. a discordant chorus of repetition, often of the radio broadcast itself.

As the preeminent propagandist himself, Joseph Goebbels said, “The lie repeated often enough becomes truth.” Or, closer to the hear and now, the Limbaugh ditto-heads will mob you and tear you, online, to pieces. Sound familiar?

The visceral and graphic elements of the typical zombie-romp, are swapped, with a more cerebral, cognitive bite. Take for instance, the opening sequence of the film, a quivering waveform on a black background. The dulcet, two-pack-a-day, baritone of Stephen McHattie (an actor who has portrayed both James Dean and the High Priest of the Spanish Inquisition) waxes philosophically on the significance of Honey, a local cat who is missing, “The posters are all over town.”

It is a marvel of an introduction, linking polymath playwright and political activist, Norman Mailer, the events surrounding the JFK Assassination, and he etymology of local architecture towards the conspiracy-pattern-recognition glitch in the human semiotic experience. Signs and wonders. An aural promise of the film’s heady (and frankly, bonkers) value proposition. There is an elegance in the bridge of this verbal introduction culminating in the visual of the title card of the film, appearing Alien-style, one letter at a time, lingering on middle fragment, which spells “TYPO.” Pure, triple-distilled, genius.

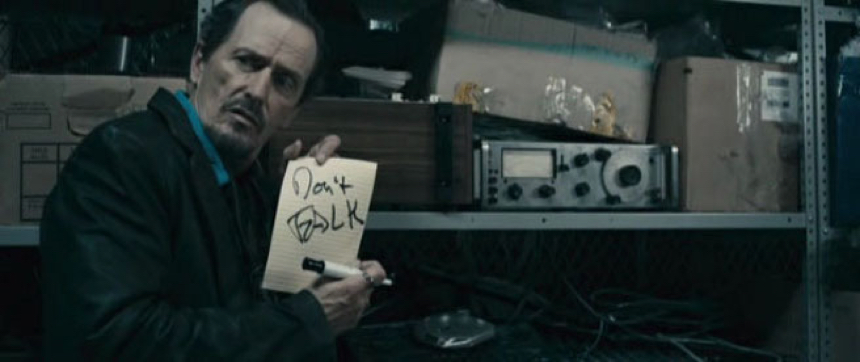

The general cinematic guideline of ‘show don’t tell’ was turned on its ear in Pontypool. Literally. For the first half of the film, it is not even clear whether or not the attacks reported to CSLY 660 AM (“The Beacon”) are even real. Mazzy himself believes, narcissistic as he is, that it is all about him. An elaborate hoax constructed as a backlash in the form of a prank, on his sardonic “take no prisoners” talk radio shtick repurposed to savagely mock the trials and tribulation of small town life. Drunken encounters amongst the ice-fishing set, or school closures.

His frustrated producer, Sidney, ever trying to get him to tone things down in that vein, insists things are no joke. Meanwhile, she has a walk-in of local actors from community production “Lawrence and the Arabians,” to buy her some time. This is a starkly amusing choice of reference, considering Pontypool barely leaves its sound booth for its entire duration, and David Lean’s epic 1960s masterpiece the local actors (and screenwriter cameo) are butchering in musical form, is one of the most visually sprawling pieces of cinema in the history of the medium. (And yet, both films have in common the world-shattering power of an idea, and its ripple effect.)

Violence and intestine-pulling gore are replaced with a plethora of science fiction and sociological ideas which are very much to the movies benefit. And yet, this in no way diminishes it as a thriller, nor an acting showcase for ubiquitous character actor, Stephen McHattie, to strut his stuff. His face on screen is a marvel, the focal point, almost always, as we lean-in with him, while he hears a disturbing account of weatherman Ken Loney (in the sunshine chopper, his dodge dart) who bears eye-witness to the outbreak of a homicide involving the severing of limbs, and a soundtrack of baby-like babble.

Tony Burgess adapted the screenplay from a few threads of his own novel, which unfolds more as an interconnected mesh of short stories, and scenarios, than a traditional narrative. Pontypool Changes Everything, in all its experimental abstruseness, was published in 1995. This was more than a decade before the ‘back of the napkin’ lustreless prose of Max Brooks’ World War Z, which used an analogous conceit — letters from the ‘front’ of a zombie pandemic — and its woefully distorted feature film adaption in 2013.

In Pontypool, there is a playfulness to the scenario that never undercuts the horror of bearing witness to something happening in real time. Zombies are often the sandbox sub=genre for the ‘horror-comedy,’ but here, the balance such that one does not undermine the other. They used to call this synergy before the corporate world gobbled up the term. The actors had the opportunity to perform the screenplay as a War of the Worlds style radio-event on CBC, Canada's national government owned broadcaster, prior to it being lensed as a feature film, on a 100% private-money budget.

Take for instance, a point where it is theorized that the virus is only spreading in the English language. The characters, with visible pain and reluctance, wince before switching to mangled French peppered with english words. A Franglais. Anyone raised in the Ontario education system, prior to the 21st century chic-popularity of French Immersion, will know this wince. And understand it, intimately.

Mazzy and his two-woman production team scramble to keep on top of the ever-evolving story from inside a church basement (The Beacon, indeed) including interrupting cut-ins from the BBC, and the French-Canadian militia, the narrative switch gears a little bit. A vast expositional stretch from a local doctor, a psychologist, who bludgeons his way into to the radio station like Robert DeNiro in Brazil, and begs the question: Are we, the voice-in-the-wilderness broadcaster, helping people to understand what is going on, or contributing to the virus’ effectiveness? If the language itself is spreading the disease, should we shut the fuck up?

The camera later pans across the production desk in the recording studio, where a dog-eared copy of Snow Crash is resting quietly in the corner of the frame. Neal Stephenson’s heady and prophetic burner of a novel begins with a gonzo pizza delivery, but it ends with a computer virus infecting people in the real world. Sound familiar? There is a glorious non-sequitur of a credit-cookie at the end of Pontypool, which seems to take place in Stephenson’s pre-cyberspace, “Metaverse.” Unrelated, but HBO is currently developing the novel as a series, after several aborted attempts at a feature film.

Vincenzo Natali's single room science fiction puzzlebox Cube, Don McKeller’s understated pre-apocalypse in miniature, Last Night, and Cronenberg’s weaponized snuff of late-night television, Videodrome (or its wonky-gamer-gate 21st century videogame cousin, eXistenZ). These cult classics (all) tip the scales towards ideas over glossy, large-canvass visuals. They allow the minds eye soar with the strange questions and possibilities raised, even as the films unfold.

In post-social media 2020, right-wing talk-radio punditry, ‘loose change’ You-Tube conspiracy channels, and Facebook algorithm-amplified-troll-farms have cemented themselves as the progenitors and super-spreaders of Fake News. As we collectively struggle with how to process the latest figures and incidents brought about by an invisible, global, contagion, now more than ever, understanding what we are witnessing is key. Especially being trapped on the other side of a screen or radio signal or podcast, this takes on significance insofar how actively progress towards understanding in lieu of passive listening. Strange times.

But, listen when I tell you, Pontypool is one of the jewels in the crown of Canadian genre cinema. If you have not done so already, go find out what happened to Honey the cat. Upon observance, the feline, all Schrödinger-like, may be many things, simultaneously, and a beacon for our times.

A decade after the original film failed to set the box office on fire, it has, as often tends to be the case in a films such as this one, developed a small but devoted cult. It would be a kindness if some production outfit would give Burgess and McDonald the funding to realize the other pieces of Burgess’s novel into other parts of a proposed trilogy.

Originally Pontypool Changes, and Pontypool Changes Everything, I am informed by the author, quite recently, on Facebook, of all places, that if a sequel/sidequel/equel happens it may be called Typo Chan, before Pontypool Changes Everything. I would like to see this happen, if only because I am not aware of a trilogy that builds the title of its source novel with each subsequent entry.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.