10+ Years Later: EDWARD SCISSORHANDS Still Makes the Cut

So, I was right about this one.

It was a chilly day in late 1990, and my younger brother and I got into a disagreement. We could only see one movie. I was a high school geek far before being a geek was in any way trendy or socially acceptable, and was therefore entirely pre-sold on Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands. My brother was hellbent on the new Schwarzenegger vehicle, I Kindergarten Cop. Both were new, and calling our respective names.

Kindergarten Cop, though, was calling everyone’s name, and quite loudly. Which was exactly why I rejected it so completely. “There’s no way that Kindergarten Cop is better than Edward Scissorhands!!”, I declared. Somehow, and I still don’t understand how, but I got my way.

I still remember huddling up at the local multiplex from the winter weather outside, being serenaded by Danny Elfman’s beautiful and surreal fairy tale score. The fireplace recollection framework of an elderly Winona Ryder recalling this fable of her youth is mercifully brief, ushering us into the weird yet familiar scene of an ignored old castle looming over an even more weird yet familiar block of seemingly innocuous track houses.

The mechanical lockstep conformity of neighborhood residents is particularly hilarious. The unfrozen husbands of the neighborhood file out of their Tupperware colored homes and into their cars and drive off to work at the exact same time. Their sunny California locale is their little corner of suburban paradise, a happy refrigerator with no refrigeration.

It’s not unlike the block where Tim Burton himself grew up, likely sans the big foreboding castle on the hill at the end of the block. Burton’s always claimed that his California suburban childhood wasn’t awful, and he isn’t resentful of not fitting in there, though the sharp, amplified world that Diane Weist’s well-meaning mother character brings Edward to had to come from somewhere.

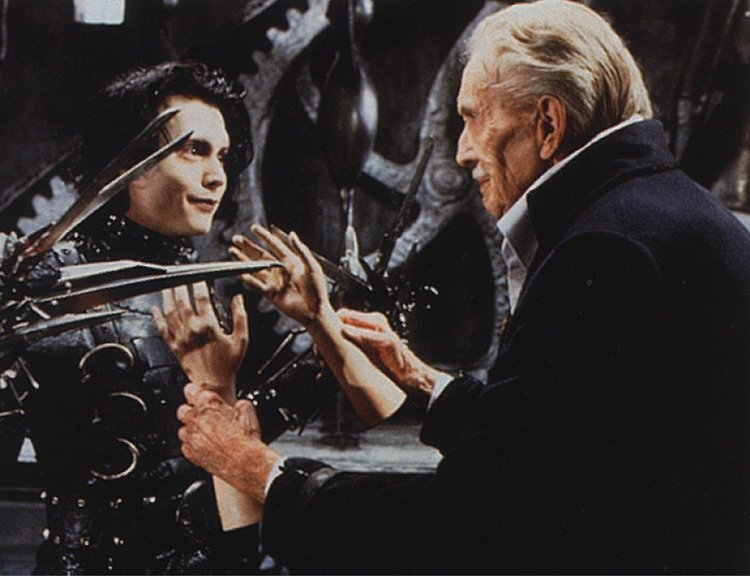

So too, then, did Edward himself. An unfinished Pinocchio assembled off-screen in the castle, which is in fact a cobwebbed wonderland, by the warm yet creepy inventor played by Vincent Price in his farewell role. The casting of Price is particularly poignant, since Burton has often cited the macabre actor as a major influence on his own life. Obviously a Burton surrogate, Edward has a sugar cookie for a heart, a body reminiscent of Micheal Jackson’s Bad get-up, and placeholder scissors in lieu of real hands, Edward is a fantasy prototype of the 1990’s emo pity-freak.

But, unlike the self-conscious and overwhelming alternative youth culture that would soon set in, Edward himself remains pure; a classically tragic outcast who must come to terms with the fact that he’ll never be a real boy. Sadly, he learns not put any real stock in the oft-feigned good will of neighbors and even his adopted family. (“Edward! I have a doctor friend who might be able to help you.”).

Still a comedy, though, the fish out of water misadventures that ensue resemble the nutty chaos of the delightful Paddington movie; even as the core situation of a kindly family taking in a needy outsider plays like a more widely honest version of The Blind Side. The treatment Edward gets from others bears shades of Get Out.

More than just an enduring contemporary classic, Edward Scissorhands also marks the moment when Tim Burton met Johnny Depp, the beginning but also the apex of a symbiotic professional relationship that spans, and arguably defines, both of their careers. One without the other simply wouldn’t have happened as largely, nor persisted as long. And without Edward Scissorhands, the easily arguable best work of both men to date, none of it would’ve happened.

One wintery day last month, I decided to show this film to my family. It had been a good decade since I’d last visited it, but Edward and company haven’t aged nor changed a bit. Our kids’ hearts went out to Edward, even as they revealed in the twisted blast that Burton was clearly having when he imagined all of it. (The screenplay by additional Burton collaborator Caroline Thompson is not to be shortchanged, either). Child empathy does not always come easy these days, so a sharp salute goes to all parties involved in bringing us Edward Scissorhands.

Kindergarten Cop, however, still awaits revisitation. My brother and I did eventually see it. Although stubborn at the time, several years later he said to me, “You know, you were right. There was no way Kindergarten Cop was better than Edward Scissorhands.” I wanted to pat him on the back, but was afraid I might cut him.