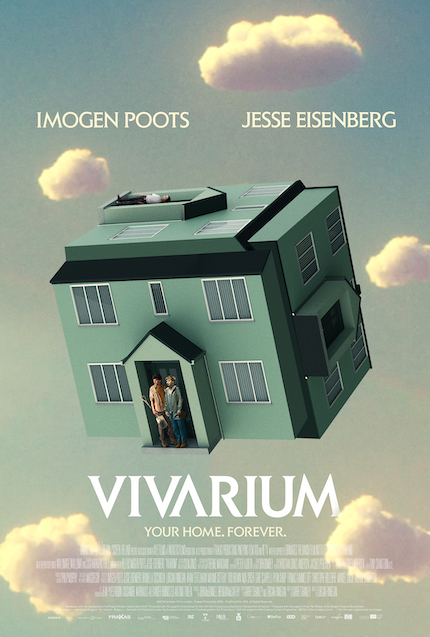

VIVARIUM Interview: Director Lorcan Finnegan On His Thought-Provoking Sci-Fi Horror Allegory Of Suburban Life Monotony

In Lorcan Finnegan’s Vivarium, which world premiered at last year’s Critics’ Week (parallel section of the Cannes Film Festival), a young couple is looking forward to take the next step in their relationship: get their own home.

Guided by an unequivocally weird estate agent named Martin (Jonathan Aris), school teacher Gemma (Imogen Poots) and school gardener Tom (Jesse Eisenberg) take a trip to Yonder, a new suburban housing development. The artificial “perfect” suburban “dream” is not really up the couple’s alley, they find the place uncomfortably creepy – specifically, house #9, which even features already a room designed for a baby boy – therefore, they want to leave as soon as possible.

When the estate agent disappears, Gemma and Tom decide it’s the perfect time for their getaway, but soon enough they realize they’re literally trapped in an infinite space of empty identical houses. No matter what they do, house #9 will always be there for them. Eventually, they’ll have to surrender to the sedentary lifestyle after they receive a box with a baby boy inside and the note “raise the child and be released.”

Vivarium functions as a rich allegory for such themes as parenting and the monotony and difficulties of everyday home life; at one point, for example, the couple’s relationship grows cold, there’s anger and, gradually, they create distance between each other: Gemma embraces motherhood and Tom gets obsessed with digging in the garden hoping to somehow find an exit from the endless suburban hell.

At the same time, Vivarium is certainly a genre piece, offering a glimpse of a unique and strange world, mainly through the fast-growing child (or whatever he or it is), who keeps imitating the adults and their voices in a creepy way, irritatingly screaming, and maintaining a series of enigmatic activities (Senan Jennings plays the young boy and then Eanna Hardwicke the grown-up version of the character).

It all works great to, ultimately, bring to the table the tragedy of when a life is pretty much wasted and how humans have become disposable within a bigger and cyclical system. Forget the recent Netflix hit The Platform, Vivarium is not so obvious as a science fiction horror effort with social allegories, it’s more thought-provoking and just superior both thematically and visually.

Now that Vivarium is out on VOD and Digital HD (definitely a good option for these coronavirus times), I share with you my interview with its director Lorcan Finnegan.

ScreenAnarchy: The monotony of suburban life is clearly one of the main themes of the film. What was exactly the starting point for you?

Lorcan Finnegan: Well, in 2011 I made a short film with the same writer, Garret Shanley, called Foxes. It was set in this kind of suburban development, which was basically a byproduct of the economic boom and subsequent crash of the economy in Ireland. There was this kind of empty development place left around the country.

The short film was kind of exploring some of the themes and ideas around: isolation, the young couple being put under pressure to kind of conform to expectations of society, but it was more of a supernatural short film. There were some ideas and themes that we wanted to explore in a much more universal way with Vivarium. That’s kind of how it began.

How was the conception of that initial scene of the baby birds?

Oh yeah, one of the inspirations for the film, along with making the short film Foxes, was actually a David Attenborough documentary on BBC about the life cycle of European cuckoos. So cuckoos are brood parasites: they don’t raise their own young, they find a surrogate in another bird. In the script we had written, like in an earlier draft, we had written a scene where this happens up in the tree, but we ended up cutting it from the script to save on budget and shooting time, it wasn’t something that felt completely necessary.

Then I felt I kind of wanted this because it set up the tone of the film. So when we were editing I decided to put it back in but just kind of simplified, using it as a few shots through the titles. Because it takes a while to the film to turn dark, and also because it’s a sci-fi film with Jesse Eisenberg and Imogen Poots, lots of people didn’t have an expectation or were wrong, I didn’t want them to think “oh, it’s going to be like Passengers or something.” I wanted to set up the tone at the beginning of the film to be in the vein of a seventies sci-fi film, with the simplicity, and kind of explaining how’s the whole film is going to play out in just the titles through nature.

How was the process and what were the challenges to create the setting of the suburban infinite space?

Tricky because the script required to create a world, which couldn’t be shot on location. We did investigate shooting on location, how would we manipulate a real space but the story, there’s no rain, no wind, no effects, the light was all kind of the same and everything looked kind of fake but tangible. The painting The Empire of Light was a reference as well, the René Magritte painting, as a kind of aesthetic. So the only way to do that was to build a set on a stage; well, in our case it was a warehouse in Belgium, where we built the facade of three houses and then scan them to make 3D and also we shot plates for 2D set extensions and then a lot of 2D mapping things as well for like the aerials. There’s very little full CGI, I think it’s in one or maybe three shots of full CGI in the whole movie, throughout it’s mostly mapping.

To me it has some THE SHINING vibes, for example. Did you have visual references to create this world?

Yeah, a lot of art, M.C. Escher was an influence, René Magritte, the art of Olafur Eliasson, he did this project in the Tate called The weather project, kind of a reference to the Sun. The repetition featured in the photography of Andreas Gursky. The photography of Gregory Crewdson.

And then in terms of movies, yeah, I guess. I love [Stanley] Kubrick’s films, so maybe there was some, [laughs] maybe I was thinking of The Shining for those aerials, I’m not sure. Films like [Hiroshi] Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes, David Lynch’s Lost Highway. Aesthetically, probably Roy Andersson’s films, like Songs from the Second Floor.

Once the baby appears the film turns into, for a way to say it, an allegory of the difficulties of life as a couple, life as a family. Can you comment on this decision?

Yeah, one of the primary reasons for making the film was kind of tapping into the anxieties of young couples, like what is that people are really afraid of these days on a more existential level? We’re not really afraid of monsters under the bed. We’re kind of afraid of our freedom being taken from us, the hopes and dreams of an exciting future being turn into just boredom, or forced into circumstances where you could end up in a relationship that you might not be fully prepared to commit to for eternity, parents becoming alienated from their children who spend all their time online, watching TV and talking to strangers on the Internet, all that kind of stuff. Social anxieties are kind of amplified in Vivarium, for that you could see how weird and frightening that kind of life could be.

Aside of the social commentary, the film is also sometimes plain creepy and crazy, with the boy and his adult voices and so forth. How important was to make this balance?

[Laughs] Yeah, I mean, it’s in the writing as well from Garret’s script. To me it was always quite funny, I quite like comedies writing that kind of uncanny valley, it’s like you’re coming up on some sort of hallucinogenic or something where things are kind of funny but kind of scary. Before they enter into Yonder and are trapped there, and then it just becomes much more of a horror film, really. It depends on your definition of horror, to me it’s a horror sci-fi and some people might just say it’s sci-fi, that there’s not enough horror elements. I’m kind of more interested in the existencial dreads and anxieties being horror, because I think it lingers longer in your subconscious, to me anyway.

There were always bits within the script that kept progressing forward and becoming darker. But hopefully there’s still that kind of core relationship between the couple, that the audience kind of relate to.

The film remains mysterious, there’s a whole weird world-building that we manage to see but maybe don’t understand fully. Why did you make the decision of leaving the audience with not everything clear after the movie ends?

To me that’s more interesting because if I tell you what you’re afraid of… [laughs] what you might imagine is probably going to be more frightening than what I show you. Different people have different interpretations of the film and they kind of project their own fears into the story, so I find that more interesting. It was always the intention to kind of not show too much, but show enough so that it can be discussed afterwards.

About the cast, Jesse and Imogen are great but so is the little boy. How was working with each one of them?

Yeah, it was great, they’re all cool. Imogen came on board first, she’s cool, she’s friends with Jesse, she was able to help bring him on board, she was great.

And then we cast for a long time for the young boy, but most seven-year-olds that you see are normal seven-year-olds who are a little bit shy, can’t remember a lot of dialog, and things like that. But Senan is an exception, he read the script, he understood the character, he was able to bring ideas to it, he kind of went method before shooting, you know? He was going around imitating people, freaking out his mother. He was great, I mean it wasn’t difficult at all to work with him or any of them. I was very lucky to have a very cool cast.

You mentioned you consider this a horror sci-fi film, so why do you think genre films are a great way to express something of social relevance?

I think with genre you're not tied to reality fully, so you can use metaphor, you can kind of exaggerate elements of things that really exist in order to look at it from a different angle, or explore ideas and themes in ways that you couldn't do enough if you're in the realm of reality. I was always interested in that, like in [David] Cronenberg's films, I always found fascinating that while we're watching entertaining genre films he's also talking of something else. The same with The Twilight Zone, we're talking about stuff with difficult ideas and true genre. I think it's just sort of a perfect vehicle for that, particularly science fiction.

I’m not spoiling the ending but there’s also this commentary of how workers [represented here by the estate agents] seem to be sort of programmed for the modern, capitalist world. In that sense, what is the social allegory you’re more eager for people to find out in VIVARIUM?

Yeah, they kind of represent a consumer, capital society in a way. Pushing people in certain directions that suits their needs and profit eventually.

I don’t think the film hammers too hard a point that we shouldn’t live a capitalist life or anything. It’s more of just to show a certain type of life in an exaggerated way so that people could make their own minds up as to what alternative may exist, you know?

But the little girl at the beginning of the film says “I don’t like the way things are, it’s horrible” [after teacher Gemma tells her how nature works: that the dead baby birds she found were probably killed by a cuckoo because it needed their nest]. To me she sort of represents a possibility for an alternative.

It’s weird because people, in Ireland anyway, for a long time people very much did a lot of social pressure to kind of conform, to get on the property ladder, to get a mortgage, to buy a place that was way overpriced, just to kind of take a step that had been predetermined for you, which is odd, is very strange. These steps are actually things that people thrive towards, they’re real goals in life. Sometimes they can end up trapping them in a life that they didn’t really fully think through.