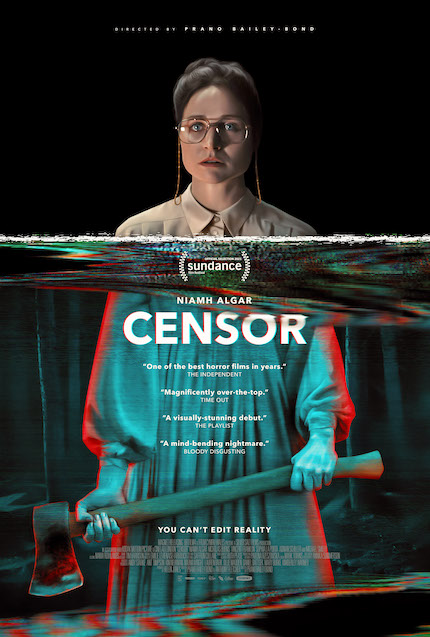

CENSOR Interview: Prano Bailey-Bond Talks Video Nasties and Horror As a Cathartic Experience

The debut feature by British filmmaker Prano Bailey-Bond, Censor tackles the argument that horror cinema, in its most violent and explicit incarnation, can inspire atrocities in real life.

Set in the United Kingdom during the Margaret Thatcher years, Censor takes us back to the times when 72 movies on video, the so-called video nasties, caused mass hysteria and harsh censorship.

Censor joins the long tradition of cinema about cinema, this time from a very particular point of view: that of the censors. The protagonist, Enid (Niamh Algar), always tries to be objective and responsible when deciding which images should be cut from some slasher/cannibal movie or, depending on the case, if they should be banned. At the same time, Enid can't overcome a trauma from her past: when she was a child, her sister disappeared while they were strolling in a forest.

Censor creates its own mythology. It mixes real movies – for example, sequences from Abel Ferrara's The Driller Killer – with fictional titles: Cannibal Carnage, a banned tape that video stores rent clandestinely derives from the Italian subgenre led by Cannibal Holocaust. These details make noticeable the director's taste for genre cinema of that time.

Censor intersperses reality with the oneiric, bordering on the nightmarish. Reality and fiction, even though they have an undeniable connection, are not the same. Censor remarks on that on several occasions, becoming a poignant and satirical comment that works for the time of the video nasties and for today.

Since its world premiere back in January at the Sundance Film Festival, Bailey-Bond’s film met deservedly with great acclaim. It has been lauded by such personalities as Edgar Wright, Sean Baker and Mark Kermode. It also won the Méliès d’or 2021, awarded by the Méliès International Festivals Federation.

Censor is now streaming exclusively on Hulu as part of Huluween, a month-long experience that features original and acquired programming in one curated Halloween themed hub. Here’s the conversation I had via Zoom with Bailey-Bond.

ScreenAnarchy: How was the process to develop Enid?

ScreenAnarchy: How was the process to develop Enid?

Prano Bailey-Bond: She ended up embodying a lot of what was happening during the period. I always saw her as representing the dangers of censorship, she censors herself.

For example, when she meets Frederick North (Adrian Schiller) and he says “you’ve got to get in touch with the elements of yourself that are bad,” she says “I don’t have any.” She will not acknowledge her shadow self because she’s so frightened of that part of herself. That is her downfall because she hasn’t learned to control it and balance it.

She’s a very rigid, crunchy character. I described her to Niamh Algar as an onion: deep down she thinks the middle part of her is rotten, so she’s created all these layers to hide that, to censor that part of herself, until she’s almost forgotten it. She’s burying it, but deep down she thinks she’s a rotten, bad person. There’s something so unhealthy about that repression.

She was living in my head for many years, she was growing. We wrote the script over the course of three years, and that’s one part of writing the character, then the next part is when you cast the actor and you start to breath life into the character and find those physicalities: things like her picking her skin, her resetting herself, her voice, her look, she’s very buttoned-up. Even talking about her neckline was interesting, she has these really tight button-up shirts at the beginning and then as she becomes more unraveled her neckline gets looser, she starts to wear different colors, they become bolder, her hair starts to become unraveled.

It was a really fun character for everybody in the team to become obsessed by. We were all really trying to gear everything around this character because ultimately you’re living in this character’s head for the course of the film.

How fun was to create your own video nasties?

When we were editing Don’t Go in the Church, me and my editor (Mark Towns) were like “I wish we’ve shot more of this film,” but obviously you could only shoot what you need for the actual film.

I made a short film called Nasty and it was during shooting Nasty that I decided that I needed to create the films, I didn’t want to try and tailor the narrative around existing video nasties, even though we see some existing video nasties in the opening titles sequence. That was because I want to take the audience on a journey and if you start to see a film that you recognize it could pull you out of the film. These films within the film had to speak to Enid, to her experience.

I enjoyed referencing some existing video nasties when I was designing them, so for example Don’t Go in the Church, I was looking at 1970s gothic horror like The Blood on Satan’s Claw. Or there’s a video nasty called Axe, which has this very strange, eerie tone, and these young girls with axes and weapons.

For something like Asunder, I was leaning more into the Lucio Fulci style of the video nasty era: very distinctive, bold lighting and colors, and a certain performance style that was fun to find, it’s slightly mannered and heightened but you still need the audience to believe this, it can’t become a pastiche because then it’s just really silly and pulls you out.

When we were editing the film and showing it to people, it felt like we needed to set up the video nasty era a little bit at the beginning and that’s when we decided to put the titles sequence together. I was keen to use Nightmare in a Damaged Brain, my favorite decapitation scene of all time is in that film. Then you’ve got really iconic images like The Driller Killer and things like Frightmare, which I wanted to use because the big stab in the eye with the pitchfork and this whole idea of watching, damage, violence and eyes. The fact that we got access to those films to use them was brilliant.

What are your conclusions about the video nasty phenomenon?

Now we can look back at the period with a much more objective viewpoint. What I see that happened during the video nasty era is what happens a lot: art and entertainment being used as a scapegoat for the bad things that happen in the world. We’ve seen it with video games and different types of music. It’s much easier to blame art than to look at the problems in society, for example the way that societies are treated by their politicians.

That is quite obvious when you look back because this is a period in the UK’s history that was very bleak. The 1980s, Thatcher’s Britain, was a hard, cold, bleak, oppressive time, where the divide between rich and poor was becoming stronger. And so of course there’s unrest in society, protests and things that make it seem like society is losing control of itself. Then you can easily turn around and say “oh, well, it’s just because we’ve got video nasties,” when it’s not the horror films that are doing this.

Even recently the New York Post critic said that fans of movies like SPIRAL “should not be allowed near animals or most other living things.”

That’s really interesting.

I wanted to make Censor because I saw it as a way of talking about my relationship with horror. Ultimately what I discovered is that horror, watching and making horror, is a cathartic thing. Most of us know that this is not real; watching a horror film is a safe space to be afraid, a cathartic and therapeutic experience.

Watching something like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is an intense, cathartic, pure dread experience. I don’t think that means that I’m then going to do something terrible because I’ve seen it in a movie, that’s not how our moral compass works. If somebody is doing that they probably got mental health problems and other issues. Go out and hurt an animal after seeing Saw is not something your average person would do. It’s just bizarre that people would think like that, it’s very limited.

What do you think about the current state of women in horror cinema?

It’s becoming more balanced and that’s really important. Women have always made horror, Frankenstein was written by a woman (Mary Shelley). We’ve got amazing horror films made by women in the past, like American Psycho and Near Dark. In the last 10 years we’ve seen Jennifer’s Body, The Babadook, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night and Raw. We’re getting much more opportunities in the genre, in terms of women getting their films financed, and that’s really positive.

The conversation can feel a bit limited sometimes because we’re always put into a similar box, which doesn’t happen with men making horror. We are not saying to the male horror filmmakers “why are you making these films about men?”

It feels like we need to shift the conversation a little bit. But at the same time it’s important to throw a spotlight on women making horror and celebrate it, because the more we celebrate it, the more is seen by the industry and the more opportunities other women will get to make their films and we can have a more balanced industry.

Filmmakers like Edgar Wright and Sean Baker raved about CENSOR. How do you feel about this? Does it add pressure to the creation of your second feature?

The support is really lovely. It’s very surreal when these filmmakers that you’ve admired for a long time know what your name is. It’s really nice because I respect those filmmakers so much, for them to have seen something in my work is a really great, big compliment.

I’m trying not to think about it in terms of pressure, because you just have to try and stay authentic and true to the kinds of films that you want to make next and focus on that.