Venice 2018 Review: Alfonso Cuarón's ROMA

In one of the scenes with narration of Y tu mamá también, where the voice of Daniel Giménez Cacho gave a greater context to the actions of the protagonists and occasionally also of the social and political environment around them, mention is made of the construction of a luxury hotel in ejidal lands, an action that eventually causes a humble fisherman in the area never to practice his trade again.

Roma - first film about Mexico by Alfonso Cuarón since that road movie/coming-of-age story about two best friends - expands that attention to the sociopolitical context of the country and puts the spotlight on a woman of indigenous origin (Cleo, played by Yalitza Aparicio ) who works in Mexico City, as a maid, for a family of upper middle class. Roma is, certainly, a political film, it’s not coincidence that there's mention, for example, that Cleo's mother is about to lose her land to the municipality; however, the protagonist does not give weight to this news because she has her own problems.

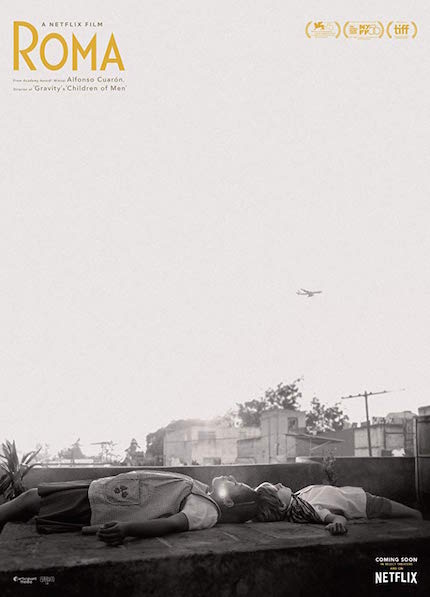

Thus, first of all, and with its impeccable black and white cinematography, Roma takes us to the entrails of a Mexican family between 1970 and 1971. The camera follows everyday life and the level of detail is seen in how Cuarón films mundane issues that, on paper, could say little or nothing, i.e. the father (Fernando Grediaga) who finds it difficult to put his large car in his narrow garage, the dog’s poop in the patio of the house that Cleo never cleans despite the scolding of her employers, the children playing, the grandmother (Veronica Garcia) who buys sweets like a box of Gansitos to her grandchildren, or the sound of the neighborhood. Roma may be located in the environment in which Cuarón grew up, but many will recognize and appreciate this type of detail.

On the other hand, if in Y tu mamá también Cuarón filmed his road trip without ignoring the surroundings of the roads traveled by the characters, in Roma he does the same with Mexico City. There is the sublime recreation of Mexico in the early seventies, from the Teatro Metropólitan when it was a cinema where people could smoke watching their movie, the music that played and the television programs that were seen at that time, to the posters of the 1970 FIFA World Cup or the propaganda that announced the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) everywhere. An ordinary trip to the cinema with Cleo and the grandmother taking care of the children and their friend, becomes a notorious lateral travelling shot that makes us feel that we are accompanying Cleo while entering a popular area of the city, to then reveal subtly and yet forcefully a pivotal conflict that involves the protagonist family.

In that sense of the dramatic charge, Cuarón takes two women, Cleo and the woman of the house (Marina de Tavira), from contrasting social classes - at a New Year's party, for example, one drinks pulque and the other rubs shoulders with some American friends - and puts them in situations not equal but with a common theme: the woman abandoned by the male figure who has decided to look the other way. Roma has a curious parallelism with Children of Men if we think that at the center of both is a pregnant woman in the middle of a hostile and violent land, and that she has no one at her side except, in this case, her "false family.”

Cleo, whose dramatic motive is her unwanted pregnancy - product of her relationship with a young former drug addict (Jorge Antonio Guerrero) of low resources and who is reforming thanks to an alleged martial arts training-, has to face a macho society but not only that, since the PRI-governed Mexico of the seventies, and certainly also of today, is synonymous with repression and war. In a masterful climax, Cuarón conjugates the violence of the notorious halconazo (the Corpus Christi Massacre), indicates where the state usually pays attention to find its executors (marginalized people, clearly), evokes those moments of Children of Men, and reaffirms Roma as another of his films with impressive formal appearance, but the one that moves you the most emotionally.

A work of many layers, equally hard that focused on humanism: every time the central family tells Cleo that they love her a lot, it's the most personal Cuarón so far showing his gratitude.