10+ Years Later: Checking-in On The Cult Status Of BATTLE ROYALE

More than ten years ago, my infatuation with surreal, thought provoking, challenging and unique anime was what led to my initial discovery and viewing of Kinji Fukasaku’s controversial and vastly influential final film Battle Royale.

The anime I refer to made me appreciate Japan’s complex grasp on heady and existential concerns, something I could only admire at the time but not completely understand. I remained obsessed with finding narratives and cult films of this ilk, as well as understanding how such a conservative place was delivering creativity of this magnitude.

My research led to a personal blog that not only likened Battle Royale to the anime I was enamoured by, but mentioned all the other good bits too; the creative violent spectacle, the Shakespearian and Grecian tragedy of it all, and of course Japanese School Girls. Battle Royale is directed by Fukasaku Kinji, who delivered many gems including the Battles Without Honor series, and who passed away at 70 during filming of the maligned Battle Royale sequel that his son took over directing duties for.

I had the strange privilege of watching Battle Royale when I relocated for the first time in my life to another state. I made some connections in the anime community on forums, and met with two like-minded friends. They gave me plenty of shopping tips and it was not before long, in a surely legal DVD store in Chinatown Melbourne Australia, that I snapped up the film, practically foaming at the mouth to watch it. In hindsight, my personal relocation helped me understand and engage deeply with Battle Royale, and at the time my undeveloped cinephile mind devoured this insanely entertaining, intense and deeply disturbing film.

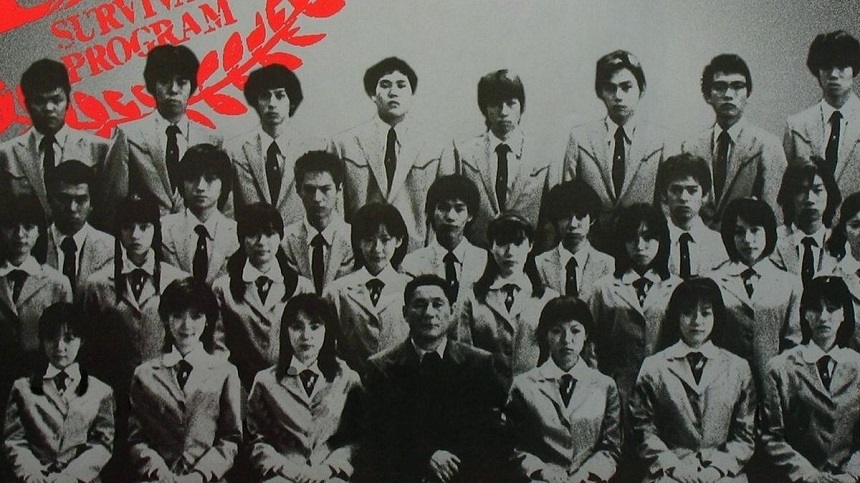

The premise is as-follows; 42 students are drugged and dropped on an abandoned island, where Kitano Takeshi plays teacher and explains to them they have been selected by a national lotto to participate in a new government legislative act; a tyrannical and grotesque event that seeks to discipline the youth into conformity by teaching them a grave lesson.

After being assigned basic rations and a random weapon (a frying pan, binoculars, grenades, etc.) the best and worst of humanity emerges as the game progresses. Characters you will never forget commit terrible but blackly humorous acts too numerous and fascinating to list. There can only be one survivor after the three days are up, but troubled youth Shuya (Fujiwara Tatsuya) and the allies he eventually gathers have other plans.

Since viewing Battle Royale, I have placed it very highly in my list, never leaving the top 10. I still think about how relevant it is in today’s climate, something which The Hunger Games also noticed, but it has been four years since I last watched Battle Royale.

Comparing it to my initial shock and awe, is the film still as bold and confident in how it relays the terrifying message of conformity and exposes the uncanny nature and psychological horrors of such an act? Or is it merely genre-fare, good for some well-made violent set-pieces and absurd drama. Does this film still hold up after 17 god-damn years?!

Battle Royale absolutely holds up 10 years later; its acerbic dialogue, blackly comic killings and surreal tone elevate the film beyond its source material, and continues to be deeply engaging, dramatic, cathartic and poignant. The original novel which covered the stories of almost all of the students on the island is condensed slightly for the theatrical cut (the version I watched) and is all the better for it.

Fukusaku Kinji expertly paces classical music that triggers key moments and thrilling turns, imbuing the editing into the woven narrative of the dozen or so fated characters. The cinematography emphasizes verdant lush greens and sombre hills, tightly compacted dangerous zones and abandoned buildings that are all genuinely beautiful and completely isolating in tone as the classmates old lives are torn away.

Like a great tragedy, the players reveal themselves, and after a truly surreal and hilarious instructional class video, the roll call begins. We get an immediate understanding of the underlying characteristics of each student as they leave the classroom, grab their rations and random weapon bag. It is the little non-verbal cues that reflect how masterfully Fukusaku directs.

There is no obvious antagonist here either, merely mixed agendas as murder becomes legal. Even Kitano, the teacher who drolly reads them the quarterly death report over classical music blaring from speaker phones (“calling for peace was a good idea, but you can’t win ‘em all”) has a soft spot for the virtuous schoolgirl Noriko.

Meanwhile two bad-ass transfer students ripped straight from a manga shake things up and provide some truly great and shocking moments in the film. Another student, Mitsuko, is a bullied bully and takes on the role of a vampire; when she is introduced she shines a torch on her face, a ghoulish visage of madness and commitment to kill all captured in a fleeting few moments.

She stalks the island, asking her former classmates to invite her in, then without warning she draws blood, feigning innocence and empathy. The film flies between characters like this, with either grand plans, desperate moves, or the desire to just kill and kill again, and Battle Royale never provides a dull moment as a result.

The relationships, motivations and human nature that made these students unruly, anarchic and angst ridden in school surface quickly on the island; even in this pressure cooker premise, Fukusaku uses every inch of the screen to detail the high school politics that came before the sick game kicked off. There are brief stream of conscious level flashbacks to their chaotic school life, but it is mostly the framing that is expertly employed here; cliques and former friends occupy the screen and there is no more memorable an example than the infamous lighthouse scene.

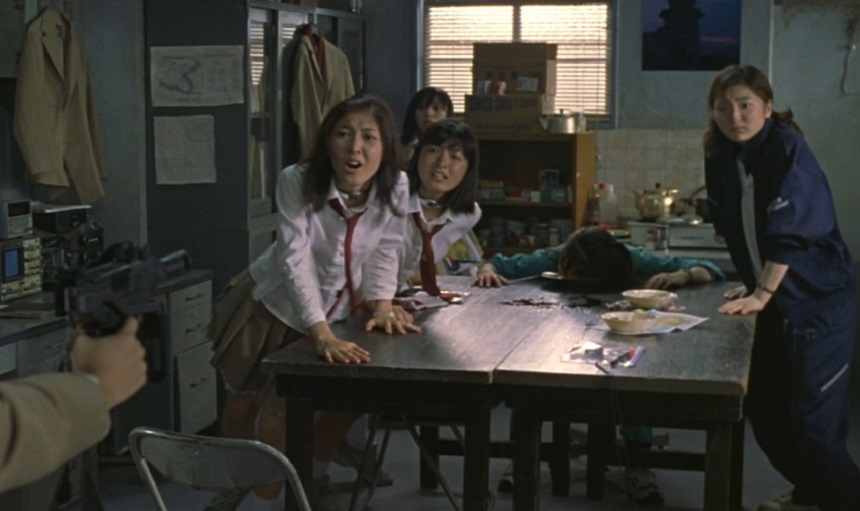

In what is initially domestic bliss, a group of friends bunker down and play house; making spaghetti and laughing like they don’t have a ticking clock bearing down on them or a collar on their neck, ready to explode. In this marvellous section of the film, one of the girls uses her randomly received weapon to poison a bowl of food after something spikes her paranoia.

Unfortunately her ill-conceived plan sets into motion a meaningless massacre. It is this scene that Fukusaku so masterfully directs, positioning the girls in different parts of the room as we witness their rapid turn from civil to homicidal, and gain a complete understanding of their past and school hierarchy. Inhibitions let fly and before we know it there is a flurry of bullets and many dead bodies, and this whiplash turn is directed with such flair and confidence like many other set-pieces the film tackles effortlessly.

Battle Royale was controversial at the time due to its political message; a rallying statement against the conservatism of the Japanese government and the neglect placed on youth. We still resonate with this message today as our lives are shaped by out of touch older generations that run the country, with not enough of a clue or care towards how to foster future generations.

Of course, the film is an extreme example of this, and its ultimate message is open rebellion, but it is a dense work that has lost absolutely nothing with age. It is imperative that I close this article by reiterating that Fukusaku Kinji was 71 when he made Battle Royale; this undeniable masterpiece pulses with anarchic energy and youthful angst in equal measure, and it always will.