10+ Years Later: PRINCESS MONONOKE, So Much More Than "The STAR WARS of Animated Features"

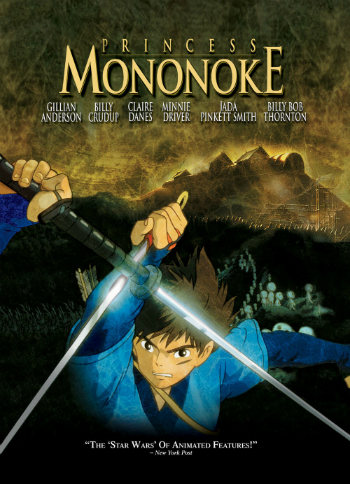

Blurbs are a strange thing. Always intended to get a certain hype going, they can easily help set up false expectations, intentionally or not. And so, while Roger Ebert was spot on when he placed My Neighbor Totoro in the pantheon of the best family films of all time (and DVDs have proudly sported his words since), a favorable comparison between Star Wars and Princess Mononoke has always struck me as a very odd and deceptive praise quote to promote home video releases of Miyazaki’s 1997 epic.

Recently, while in the process of upgrading my Studio Ghibli collection (read: replacing old VHS tapes with prettier Blu-ray editions), I again stumbled upon the strange quote, still in use on a 2014 DVD/Blu-ray combo of the film. Since I recalled disagreeing with it without quite remembering why it had rubbed me the wrong way, but also because it had been close to a decade since the first and only time I had watched what is often still referred to as one of Miyazaki’s greatest masterpieces, I decided it was high time to revisit Princess Mononoke.

‘Finding fault’ with an old New York Post review (the source to which the DVD attributes the favorable Stars Wars comparison) is certainly not the purpose of this re-visitation. Nor do I want to take aim at the Star Wars saga (of which, for the most part, I too am a fan). But, placing Princess Mononoke next to George Lucas’ space odyssey offers a fruitful starting point for identifying the film’s defining characteristics as well as helping to explain why my teenage self was not terribly impressed with Miyazaki’s eco-driven tale of warring factions.

See, at age 18, the main ‘problem’ Princess Mononoke presented me with was that I had a hard time choosing sides, a must which Disney had ingrained in me as something straightforward, thanks to the clear-cut if not perversely stereotypical depictions of right and wrong in their animated films. While Star Wars amounts to a classic battle between good guys and bad guys, the opposing forces in Princess Mononoke’s conflict are drawn in shades of grey.

There is, on the one hand, Lady Eboshi, introduced to us as a woman who is escorting merchants back to Irontown when all of a sudden the convoy is attacked by Moro and her wolf children. Anything but a damsel in distress Eboshi goes beyond fighting off the threat and seeks to exterminate her opposition. Fearless and not to be trifled with, we come to see her as a business-savvy entrepreneur who calls the shots in Irontown and keeps the men in check.

She has made women an active part of the workforce in the city she built (by buying back their freedom). Employed at the iron forge they put food on the table in the idiomatic sense, by creating the materials which can be traded or sold in exchange for other provisions. Not only do women play a vital part in Irontown’s day-to-day sustainability, Eboshi avoids shunning the sick and disabled by having them design the weapons in her arsenal. And yet one has to wonder: what is the line between kindly giving them a purpose and exploitation?

If on occasion she acts for the greater good of her city and its inhabitants, it also becomes clear she is selfish, motivated by greed and singularly intent on expanding her domain. After all, having depleted the natural resources in the river, Eboshi plans to penetrate deeper into the forest, keen on appropriating the deer god’s lands and ready to annihilate any number of animals that stand in her way. As a colonizer and representative of a type of modernization that must come at the cost of nature, she is a catalyst of violence.

Fighting for opposite ideals but equally radical in her approach is San, the knife-wielding, wolf-riding girl who dubbed herself the titular Princess Mononoke. Certainly no Disney princess, San too represents a flawed character and seems deliberately designed as such.

Together with the wolves who raised her, she fights for the preservation of the forest but her immediate reaction to pretty much any situation is to draw a knife and lunge headfirst into violent confrontation. Even though San’s motivation is understandable and even if her actions are fueled by a hatred that is fanned by human provocation, does the end justify the lethal means?

Caught in the middle of this altercation is Ashitaka, the story’s altruistic hero. He sets out to find a cure for a curse that is an indirect and unwanted side-effect of Eboshi’s heedless, militaristic expansion, yet bears no ill will towards either party and tries to act as a neutralizing force. If Eboshi is a symbol of modernizaton as destructive progress (that appropriates land unencumbered by ecological concerns) and San is a staunch supporter of nature (yet close to an eco-terrorist given her lethal means of resistance) then Ashitaka stands as an embodiment of Miyazaki’s pacifism, a figure who not only seeks to prevent the further escalation of violence but wants to formulate an alternative to the collision course that both extremes find themselves on.

Princess Mononoke is interesting to consider as Miyazaki’s rumination on how mankind’s need for self-development and modern society’s perennial expansion can be espoused to a respectful treatment of the earth we inherited. During a pivotal scene that sums up the film Ashitaka literally puts himself in between Eboshi and San, keeping them at bay and saving both from mutual destruction. Ashitaka is the only one who sees commendable qualities in each character. In the end, his interventions help point to a future in which humans and animals can coexist next to one another as equals without one feeling the need to dominate the other.

Insofar as territorial expansion is a motivation that fuels the conflict the Star Wars parallel does hold up, but in terms of how the clash is represented Princess Mononoke could not be further removed from the space epic. While the latter celebrates lightsaber duels and relishes the grandeur of space combat, the former builds towards a huge battle between humans and animals steering clear from spectacle. In fact, when Okkoto and his boar warriors attack we are never treated to an actual fight, only confronted with its grizzly aftermath – one harrowing shot of dead bodies strewn about. We see the carnage and one guy sitting in a corner, crying, shocked by the horror of war and the immense losses on both sides.

Even though Princess Mononoke was the most action-oriented Studio Ghibli film I had seen at eighteen, I didn’t grasp that the action is mostly beside the point. Having rewatched it now I find it easier to admire what Miyazaki is going for thematically even if I still don’t find the film as instantly enjoyable as some of his other works. Films like Kiki’s Delivery Service and My Neighbor Totoro have lead characters that audiences can more easily identify with, while also tackling more universal, relatable rites of passage. With fewer extravagant fantasy sequences and a more solemn tone overall Princess Mononoke offers less of an immediately gratifying experience than for instance Howl’s Moving Castle or Spirited Away.

On the whole, Princess Mononoke seems more eager to give us something to chew on rather than to entertain us. After all, instead of transporting us to another world that brims with vibrant color and the promise of enchantment, Miyazaki’s 1997 epic is a fantasy rooted in reality, intent on confronting viewers with just how ugly mankind can be (which puts in perspective the film’s early depictions of beheadings and dismemberment).

As an indictment of the pointlessness of war, the nature of mankind, how indiscriminately we can kill, and a film that aims to find a peaceful middle ground as an alternative to extremism it’s easy to see why, with age, the film has become more valuable to me. In light of a certain president’s recent decision to turn his back on climate change, and faced with an increasingly violent world that seems to be radicalizing on a daily basis it is striking (and harrowing) that twenty years after its Japanese release the message of Princess Mononoke rings truer and more relevant than ever.