THE SHROUDS Interview: David Cronenberg, Wrapped in What the Light Reveals

When I’m interviewing someone as respected as David Cronenberg, the temptation to revisit as much of his work as I can ahead of time looms large.

It’s seldom practical unless one is writing a book. Especially when the work spans such a long period of time. But Cronenberg has also been remarkably consistent in his choice of themes.

Equally consistent are the questions asked of him by journalists. Fans, academics, professional critics and journalists have all explored the same territory, and yet interviewing him stills feels like probing a mystery, visiting a barely lit catacomb, where you expect to find something mysterious and unsettling.

The term body horror was applied to him and his work long ago, due mainly to the fact that his first widely seen commercial films were horror films in which the human body undergoes monstrous transformation through disease and or technological fusion, usually presented in the most visceral fashion that special effects allowed for at the time.

The label is one that Cronenberg is quick to contextualize, if not marginalize: “Of course that came from a journalist. A young woman, I can’t remember her name, and it stuck.”

Other monikers like the “king of venereal disease” and “baron blood” still have the power to make him chuckle. “You, this stuff. I understand," Cronenberg says, "It’s like the word Cronenbergian. How cool is that for me. I have my own adjective. When somebody says Felliniesque it’s a compliment, generally so.”

Of course, it also means his work has been incredibly influential. To say that he has shaped the horror genre is like saying Stephen King was this guy who sold a few books.

Like most horror movie fans or critics would be, I am happy indeed to have a chance to talk with him at length. I don’t have a bucket list per se. But this conversation would have been on it.

He was in town for two sold out screenings of his new film, The Shrouds, followed by in person Q and A’s. At 82 years old it would be easy to imagine him doing all his publicity for the film via Zoom. Instead, he’s flying all over the place. I asked him about that choice.

"I could be very content to just be on my own, alone at home. But I love sociality. This, what we’re doing right now, is a source of great pleasure to me.”

In talking with him my first impression is of someone of great intellect who nonetheless wants to connect. He has soft eyes, but they penetrate. I felt seen immediately and I also sensed a great deal of joy. The warmth radiates.

I’m grateful for it. It’s also easy to imagine him inspiring the large group of collaborators that have formed around him. Together they’ve created a remarkably diverse group of movies. Notwithstanding the horror/fantasy and sci-fi films that are now considered classics, they have done equally great work in less easily defined narrative territory.

How would one classify the brilliant A History of Violence (2005)? An adaptation of the equally brilliant graphic novel by John Wagner and Vince Locke, in which a gangster, Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen), who is hiding in retirement is forced to settle scores with his ruthless older brother Richie (William Hurt). It’s part neo-noir, has elements of horror and thrillers, and finally settles into a family drama telescoping out into the same concerns about violence in American society that seem even more urgent some forty years after it’s release.

Then there’s Cosmopolis (2012), a film that seems more relevant than ever taking place entirely in the back of a limousine where a variety of sycophants, hangers on and others accost an at times bored and finally thoroughly disillusioned billionaire, Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson). It was a relatively early turn in non-franchise acting by one of the most visible franchise players in the world. Pattison had enjoyed success as Cedric Diggory in the Harry Potter films and become a full-blown heartthrob as Edward in the Twilight series.

Cronenberg was one of the first directors to see the now A list stars possibilities beyond sparkly vampirism. “I knew he was underrated at that time," says the filmmaker. "He was remarkable and I do think it helped him to embrace that. I really thought that film would be received differently. Of course, now it’s obvious what a great talent he is.”

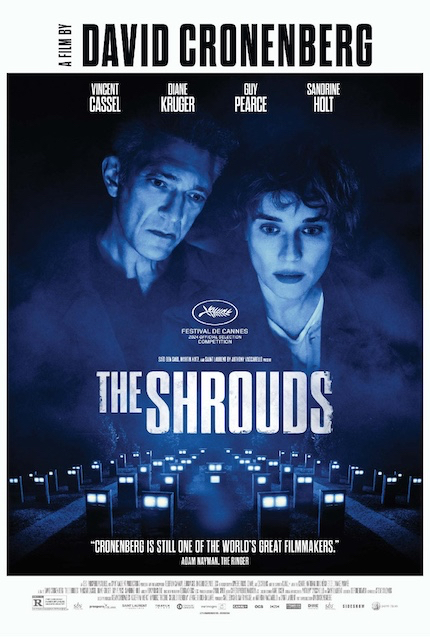

The Shrouds is an equally odd film, but unlike A History of Violence and Cosmopolis, it was written entirely by Cronenberg himself. It tells the story of Karsh (Vincent Cassel), a husband who is so haunted by the death of his wife (Diane Kruger) that he invents a way to watch her in the grave as she slowly decays. Slowly, he becomes afraid that his GraveTech technology has been hijacked by international hackers who plan to use it as a weapon.

All this occurs while he’s trying desperately to get his company off the ground and manage the advances of his dead wife’s twin sister (Diane Kruger), and the wife of one of his potential investors (Sandrine Holt). Despite the help of his employee and former brother-in-law (Guy Pierce) and AI assistant Honey (Diane Kruger), he finds himself drawn deeper into the conspiracy, as reality bends around his perception of what is and what he wishes to be.

The Shrouds would seem to be an intensely personal work. Cronenberg lost his wife in 2017 and it’s one of the things he’s most open about. Still, he shoots down the idea of his art as personal catharsis.

I ask him if he perhaps much of his art is a way to address the subject of aloneness or isolation which has seems to have been a a major theme in his work over the years.

“Well, when someone you’ve been with for almost 40 years is suddenly gone, you don’t stop wanting to be with them. The Shrouds is definitely about that sort of working through grief. But I wouldn’t call filmmaking catharsis, really. At least not for me”

But it’s also about hiddenness, isn’t it?

Almost all Cronenberg’s characters are willfully hidden. The Brood (1979) features a woman conjuring murderous rage children from the deepest parts of her psyche. In Videodrome (1983), Max Renn lives in a deeply isolated cultural ghetto and falls prey to his own sublimated violent impulses.

The characters in Scanners (1981) and Johnny in The Dead Zone (1983) are isolated and on the run because of their extrasensory gift. In The Fly (1986) scientist Seth Brundle has sequestered himself in a sparsely furnished warehouse with only a lab baboon for a companion. In Dead Ringers (1988) the Mantle twins meet a tragic isolated end in a tony but increasingly disheveled penthouse.

Ralph Fiennes struggles to remember his own history in Spider (2002) and, in the aforementioned, A History of Violence (2005) Viggo Mortenson’s Tom has so fully immersed himself in a fake identity that it is questionable if he even remembers entirely who he is/was. There are other examples. But isolation, aloneness, seems to be a central truth of the Cronen-verse.

In The Shrouds there’s a suspicion that Karsh may be purposefully cutting himself off from the rest of the world to keep from dealing with his new reality of needing to work through his grief. At the very least he is isolated, unable to connect in the old way though he desires connection.

Cronenberg says: “Or is this simply the way he’s working through it? That’s a good insight. I love it when people make those connections. We are alone, aren’t we? We certainly seem to die alone and struggle to build and maintain connections.

"I believe that when we are done, we are done. I’m not quite an atheist but I have few religious inclinations. It’s when religion tries to lead us away from the body that I completely reject it. What am I without a body, really?”

I point out that I’ve always found his work to be imbued with a very trustworthy sense of the spiritual and that true faith, if you will, has more to do with following the lead of goodness and love than in creating dogma or “figuring out” a static group of understandings of the world. At a certain point all of us are looking dimly through a glass.

“I can get behind that. There has to be some humility about all these things. In The Shrouds it’s about hanging on to something that is inevitably ethereal no matter how much we want it to remain physical. There’s even the question am I really still me without you? Was there an us? Is the us still approachable? Does technology play a role in that, or does it get in the way of something more important?”

This was where our conversation inevitably turned to the familiar role of technology in what I’ll call the Cronen-verse. I asked him if perhaps the growing intimacy between humans and the technology they use has outsourced too much of our humanity,

“You mean to the point where we don’t even see it anymore? That is a question I’ve always asked in my stuff. Is it better or worse today? Is it helping or hindering relationships. I think the answer is both but there’s inevitability too. I really don’t know how we could avoid it. Every technology has this effect.”

So is he saying his work is cautionary? “Maybe in some sense. I’m surprised more people haven’t picked up on the humor in The Shrouds."

Was the extensive use of Teslas meant to be humorous? Or in any way a response to the current wave of negative publicity around founder Elon Musk?

“Oh, I wrote this long before that. You know I’ve owned a ton of Teslas. It just seemed like a good idea. For the environment etc. But you aren’t the first person to notice that.”

I ask him if he’s afraid that someone is going to draw a big dick on his current Tesla now. That would be pretty Cronenbergian. He laughs.

“Oh man. Yeah, I guess that would be okay.”

In The Shrouds it could be argued that much of the humor Cronenberg is referring to emerges from the lure of conspiracy theories and their promise of making sense out of our personal histories. The film doesn’t fully explore it but there is an aura of absurdity felt throughout.

During dinner Karsh is describing his macabre business model to his date as a coffin is dug up and hoisted mere feet away. It’s a transgressive moment we view through a large window that is reminiscent of the screens that are part of GraveTech and it does more than border on satire.

It is also a key moment in which the full awkwardness of Karsh’s business model becomes painfully apparent. To experience the reality, he wants Karsh must be willing to dig up that which we instinctively feel should stay buried. But doing so seems to keep him stuck in time, unable to go forward. He cannot fully grasp his future.

What is it about conspiracies that draw Cronenberg as a storyteller?

“Well, in the case of The Shrouds it's very much a look at what is going through this man’s mind and emotions as he navigates grief in a chaotic world. Of course, he’s going to try and make sense of all of that.”

I ask him if maybe we’re all a little conspiratorial in our thinking.

“We all do it. We look for patterns. We try to put things together to see if they fit one another, complement one another. It isn’t necessarily crazy to do that. It’s one of the things that I suspect make us human.”

Cronenberg’s comments are reminiscent of the observation made by many critics and social observers that horror films offer a way to acknowledge the realities we are afraid society is blind to or ignoring. The terror that we are alone, unheard, unseen, unsafe.

I wonder if this aspect of The Shrouds is the most personal aspect of it for the director.

“Oh, I’m looking for patterns like everyone else. I try to be open, which is necessary when you’re telling a story. They have to connect to the characters and about where they wind up.”

I wonder if the world has gotten smaller for him as a storyteller, if getting older makes him want to rush to get all his stories told.

“No, not at all. For one thing I’m pretty sure the world doesn’t need another David Cronenberg film. For another, no matter what you do, filmmaking is a process that takes a long time. You can be in a hurry but the people who finance things won’t be. We made The Shrouds so cheaply. That’s the only reason it gone done. I was talking to Marty Scorsese and we were both saying the same thing. You would think that someone like him would just be able to make just about anything he wants. But that’s so not the case. He has just as much trouble getting his films financed as any of us. It’s always the biggest problem for me.”

In The Denial of Death, author Ernest Becker frames the human search for meaning with the term immortality projects. In simplest terms he suggests we create things that we hope will survive us as a symbolic hedge against the knowledge of inevitable death and that consciously or unconsciously we understand this to be a heroic act. A way to not only rage against the dying of the light but to become part of the light itself and continue. I find this a deeply spiritual notion though Becker himself largely eschewed religion, opting to apply his concept as an umbrella under which activities like religion sit. But there is a difference between the activities of religion and a notion of actual intuited meaning. Between an abstract notion of constructive creativity and the embodiment of it.

As C.S. Lewis said in Meditation in a Toolshed, “I was standing today in a dark toolshed. The sun was shining outside and through the crack at the top of the door there came a sunbeam. From where I stood that beam of light, with the specks of dust floating in it, was the most striking thing in the place. Everything else was almost pitch-black. I was seeing the beam, not seeing things by it.

"Then I moved, so that the beam fell on my eyes. Instantly the whole previous picture vanished. I saw no toolshed, and (above all) no beam. Instead, I saw, framed in the irregular cranny at the top of the door, green leaves moving on the branches of a tree outside and beyond that, 90 odd million miles away, the sun. Looking along the beam and looking at the beam are very different experiences.”

Is Karsh focusing a sort of light in The Shrouds determined to see what it can show him? To not let death and darkness have the last word. Is this what Cronenberg is doing by making movies?

As tempting as it is to view any artists work as a sort of immortality project a la The Denial of Death, it seems clear that Cronenberg thinks less in terms of legacy than the questions that haunt him and everyone else and what he and his characters might have to say about them. It’s as if he knows he is standing in a dark shed (one we all share, religious or no) and knows it is important to see what he sees in the light.

This seems to be the true dark magic of the man and his art. He invents ways to look inside as deeply as the bizarre gynecological instruments invented by the Mantle twins in Dead Ringers and he knows how to invite others to look in with him. But he knows no matter how deep we go the questions remain. Yet Cronenberg seems as unlike his obsessed neurotic characters as I can imagine though I’m sure he would disagree.

We wrap up the interview with chit chat about our families and I asked him if he was proud to see his kids doing such great work around the same themes as their dad.

“I’d start with the word love," says Cronenberg. "I love my kids. Of course it’s fun. So, I guess I’m a proud dad. I had something to do with that. But the themes never go away. We all use the themes whether we’re making movies or not."

The Shrouds is now playing, only in movie theaters. Visit the official site for locations and showtimes.