Blu-ray Review: Criterion's ESSENTIAL FELLINI, an Eternal Tribute to an Eternal Filmmaker

Part one of a two-part investigation into the Criterion Collection's glorious multi-film box set.

The company of entertainers are moving in, the greasepaint is thickening, and libidos are boiling in step. Creative energy is on the menu, forcefully and unrestrained. In other words, amid the mundane drain of the everyday, the circus of Federico Fellini is in town. And what an experience it is!

*****

The fact that this set is far from complete in terms of Fellini’s films does not mean that it is not comprehensive. Titles span from the start of Fellini’s career to quite nearly the end, covering all of his major thematic shifts and often wild creative phases. Included are all of the Fellini titles that Criterion has ever released, many of which have not been previously made available on Blu-ray due to having been forced out of print for many years. All the heavy hitters- La dolce vita, 8 1/2, La strada, among others- are here. Also included are Criterion newcomers Il bidone (1955), the vital short Toby Dammit (1968), and Intervista (1987), meaning that, in this one fell swoop, and once Kino Lorber releases Fellini’s Casanova in December, almost all of the filmmaker’s singular feature films will have come out on Blu-ray in North America (the stomping ground of this critic). Not only is it about time, it’s the perfect time- the 100th birthday of the director. (Fellini was born January 20, 1920, in Rimini, Italy).

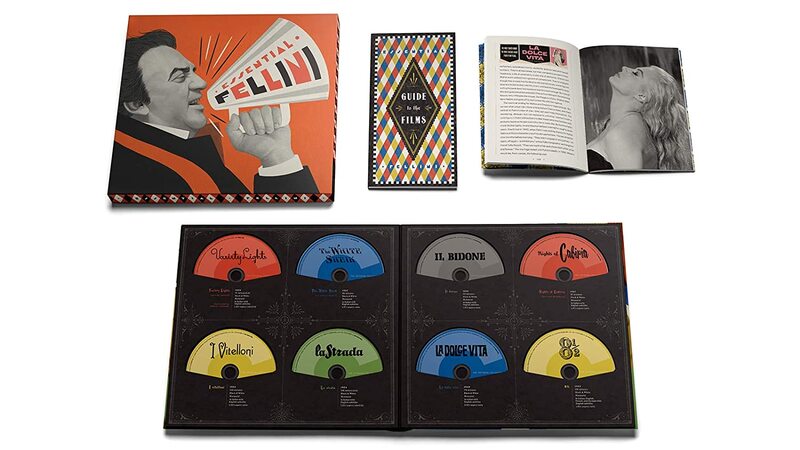

In a brutal year that’s been no less brutal to film buffs, Criterion has really come through. For the venerated boutique label, 2020 has yielded multiple high-end boxed sets amid the usual steady stream of excellently curated diverse stand-alone releases. The fifteen-disc/fourteen-film Essential Fellini (newly available for purchase) is the must-buy capstone in a year that’s included major new sets devoted to Bruce Lee and Agnes Varda, not to mention Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project Volume 3.

In this first of two installments devoted to unpacking the films contained in the record-album-sized square flat box, Fellini’s early-to-mid-career work is individually capsulized, intended to provide an efficient engagement with each title. Following that, some information on the set itself. (Bonus features, transfer quality, what lies ahead in the second installment of this review…)

For now, these are the Essential Fellini titles covered below:

Variety Lights (1950)

The White Sheik (1952)

I vitelloni (1953)

La strada (1954)

Il bidone (1955)

Nights of Cabiria (1957)

La dolce vita (1960)

*****

Appropriately enough, it begins with a show. 1950’s performer-centric Variety Lights, Fellini’s first film (co-directed with Alberto Lattuada), is also the first act in Criterion’s brand-new centennial career retrospective Blu-ray box set. Throughout his impressive, varied, and controversial career, one of several themes that never quells is that of the perseverance of showmanship. Sometimes it’s exhausting, sometimes it’s euphoric- both for the viewer and for the characters, on stage and off. Quite often, it’s both. This is pointedly true in terms of how the escapism of showmanship collides so often with the drudgery reality, and how the two very different elements feed off of one another.

Variety Lights is as good of a place to begin with Fellini than most any other options. Released the same year as Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve, the film also shares the plot element of the film’s central starlet opportunizing her way to the top. (In this case, the engaging Carla Del Poggio). It’s show-people traveling from town to town for their next gig, and all the inner drama that happens throughout. From this first film, Fellini’s lovely wife Giulietta Masina is present onscreen, just as she would increasingly go on to be throughout his filmography. Variety Lights is an impressive-enough piece of work, well-constructed and naturally acted with no sloppiness.

Perhaps that initial precision was courtesy of Variety Lights co-director Lattuada, as Fellini’s next (and first solo) effort, 1952’s The White Sheik (Lo sceicco bianco), is not nearly as tidy. Thematically, the film is on-point, insomuch as it deals with notions of showmanship as escapism from one’s reality. It is the tale of vacationing newlyweds separated when the bride (Brunella Bovo) runs off to meet the true love of her life, the White Sheik- a romance novel hero brought to life in movies by a hammy actor with an inflated ego (Alberto Sordi). The husband (Leopoldo Trieste), flummoxed and left in an embarrassing bind by her disappearance, spends the film making excuses and searching for her, but mostly making awkward faces at the camera. While not a bad romantic comedy, it is, by Fellini standards, an unstable effort. He himself admits as much about “his early work” on an audio interview included on the disc.

But, Fellini shouldn’t be so hard on all of his early work. I vitelloni (The bullocks or The layabouts), his very next picture, quietly ranks among his absolute must-sees. Though the filmmaker would frequently shirk notions of his films as autobiographical, there’s little room for any such denial here. Crafted with remarkable nuance and raw humanity, the subsequent success of I vitelloni would take Fellini far- not unlike the home-tethered protagonist of this film (Franco Interlenghi) who ultimately must make the hard decision to leave sleepy Rimini for a larger world. Notably, the cinema of George Lucas (particularly American Graffiti, even with its partially Italian moniker) owes much to I vitelloni in terms of thematics.

As good as I vitelloni is, the next film, 1954’s La strada (The road), is even better. Giulietta Masina is Gelsomina, a naive waif of a young girl who is pawned off by her mother to traveling strongman performer Zampanò (Anthony Quinn). Zampanò is brutish and emotionally abusive to Gelsomina as he teaches her the ropes of clowning for tips for crowds on the streets. As the pair move on to slightly bigger and better career opportunities, their union becomes increasingly strained, even torturous. La strada is a pure heartbreaker, even as it also resonates as somehow inspired. It rides a tightrope of its own making; and having stayed the course, is now being recognized as one of the most dramatically influential films ever made. La strada wasn’t always recognized as such, though today it must be acknowledged as canonized World Cinema.

It’s been said elsewhere (in a bonus feature on Criterion’s new Moonstruck disc, to be exact) that Italians tend to focus most on food, sex, and death, and in that order. Notice that dreams, religion, and crime don’t make the cut. Though Italian cinema is all too often pigeonholed with mafia and criminal tales, Fellini demonstrates little to no interest in such things. This is even true of 1955’s Il bidone (The swindle), a film all about professional con men. Fellini is far more intent on depicting the sheer heartlessness in their operations, which target impoverished people living in remote areas.

Led by a slightly more vulnerable than usual Broderick Crawford, the despicable nature of these thieves demonstrate on an internal level how crime does not pay- even when it’s pulled off successfully. Very recognizable seeds of Il bidonehave since sprouted in films such as Michael Mann’s Heat, Drew Godard’s Bad Times at the El Royale, and Oliver Stone’s U-Turn. These are criminals as workaday grifters, survivalists using immoral skills fostered during Italy’s time of postwar desolation. The film isn’t so much the gut punch of La strada as a felt depletion of oxygen.

By the late 1950s, Italy was in fact quickly turning a corner in terms of living conditions thanks to a postwar “economic miracle”, courtesy of U.S. financial aid. There’s an old dismissive adage that the best thing that can happen to a country is to lose a war to the United States. Giving undo possible credence to that notion for just a minute- suffering, death, and mass destruction aside- it must be asked, really?

1957’s Nights of Cabiria brings back Giulietta Masina’s spunky titular “working girl”, first introduced in passing near the end of The White Sheik. A decorated near masterpiece if not a masterpiece, this is Masina’s finest hour. Though an impossible prostitute (a word that’s never used, at least according to Criterion’s astute subtitles), Cabiria is tragically naive in the ways of love. If not love, per se, then perhaps life. Several key scenes play out before desolate postwar landscapes, the cranes of supposed progress rebuilding the city into an expansively modernist and efficiently sterile version of its former, ancient self. Another Fellini classic, another soulless soirée. In this film’s ill-advised night out, Cabiria mambos the night away and into our hearts (not necessarily in that order) in an upscale yet skeezy night club with no shortage of ominous snake ladies at every table. Cabiria is out of place in this place, but how could she possibly mind when she’s have this much fun?

But all of that is fleeting. Though lovelorn and terse, this is still the portrait of a woman who, nevertheless and very deep down, holds out hope for love. Nights of Cabiria is a powerful film; a case study character study that is not without social messaging. (For what it’s worth, it took home the Best Foreign Language Oscar at that year’s ceremony. Twelve years later, Bob Fosse would make his film debut with his not-uninteresting Americanized musical version, Sweet Charity). All around Cabiria, in the distance, the world is impersonally signaling to her that things can get better. But what consequences does such an economic band-aid also bring?

With 1960’s La dolce vita (The sweet life), Fellini truly hits the sweet spot of his career. The rapid economic turnaround happening in Rome and elsewhere leads the by-now supernova-hot filmmaker to deep-dive into the decadent malaise that is indeed infecting the soul of The Eternal City. For gossip journalist Marcello (played by Fellini surrogate-among-surrogates Marcello Mastroianni), the existence of party after party and woman after woman is a soul-eater. A simple boy from humble Rimini, Rome has become his… but was never his. Certainly, it’s not now, what with soulless postwar constructions sapping the character out of the landscape, newly flanked in utilitarian blankness. He too is built up thusly but devoid of what should be there.

Fellini has spoken of how La dolce vita is a rumination on what happens when the notion of sin exits a culture. It’s not the first time Rome has danced with the Devil in this particular way, though Fellini’s exploration, for all its moral and ethical weight, is as secular as could be. Nevertheless, the cost of a life lived amid consequence-free everything is laid bare in the film’s final minutes. There are no answers, only an indelible acknowledgment. And for this, that’s more than enough. La dolce vita itself is something beyond a masterpiece. It is an eternal paean and forever-echoing lament of both the human condition in the second half of the twentieth century, and a vital cinematic statement of its own time. We may never be able to resist Anita Ekberg as she wades into Trevi Fountain, though Fellini makes it clear that the seduction towards the high life is, in the end, anything but sweet.

*****

From this point, the work of Fellini takes a distinct turn. With 1963’s seminal 8 1/2, the filmmaker shatters not only the expectations set of his career trajectory up to this point, but nothing less than the expectations of narrative cinema itself. The film lays the groundwork for an uncompromisingly rest-of-career rife with increasingly grotesque detachment from typical “reality”. In the upcoming second half of this exploration into Criterion’s Essential Fellini, the following titles will be covered:

8 1/2 (1963)

Juliet of the Spirits (1965)

Fellini Satyricon (1969)

Roma (1972)

Amarcord (1973)

And the Ship Sails On (1983)

Intervista (1987)

And, as Criterion itself is want to often promise, “More!”

For those who only want the quick version, here is Criterion’s very broad listing of what this set has to offer:

• New 4K restorations of 11 films

• New digital restorations of Toby Dammit and Fellini: A Director’s Notebook

• Feature documentaries Fellini: I’m a Born Liar and Marcello Mastroianni: I Remember

• Audio commentaries, behind-the-scenes documentaries, interviews with Fellini, video essays, and more

• Deluxe packaging including two books with notes on the films, new essays, and Fellini memorabilia

Now then, with tremendous gratitude to Criterion statistician extraordinaire Michael Hutchins (and with his full blessing), I share some of his words and his detailed, expert breakdown of the set’s many, many offerings and details, as sourced from the Facebook Group, “Criterion Now”:

“What appears to be a first when it comes to Criterion licensing, these 14 films are from 10 different sources! 17 logos are given on the removable credits sheet on the back of the box.

The set includes six audio commentaries, including five from previous releases (La strada, 8 ½, Fellini Satyricon,Roma, and Amarcord) and a new one (Il bidone). Two of the films have optional English soundtracks (La strada and Amarcord), both from previous releases.

There are 67 other supplements, totaling more than 29 hours.

⁃ 2 films by Fellini (1:35) [Toby Dammit and Fellini: A Director’s Notebook]

⁃ 17 documentaries (17:45)

⁃ 19 video interviews (5:42)

⁃ 5 audio interviews (2:31)

⁃ 10 trailers and radio ads 10 (0:29)

⁃ 9 galleries [two are presented as videos (0:22), the others as stills]

⁃ 2 introductions (0:21)

⁃ 2 deleted scenes (0:21)

⁃ 1 video essay (0:09)

New to the Criterion Collection on disc:

⁃ 3 feature films: Il bidone, Toby Dammit, and Intervista [the first two were first available on the Criterion Channel in standard definition.]

⁃ 1 audio commentary: Il bidone

⁃ 10 documentaries (12:27) [Second Look: Fellini (2:11) is presented on four discs, and Marcello Mastroianni: I Remember (3:14) is presented by itself on the last disc in the set.]

⁃ 2 archival interviews (0:57)

⁃ Other than the one new audio commentary, there are no new Criterion-produced supplements. (Damn you, COVID-19!)

The set includes two books. The first is an 80-page guide to the films written by Italian film scholar David Forgacs. The second is a 150-page essay collection, introduced by Bilge Ebiri, and profusely illustrated. It includes essays by Michael Almereyda, Colm Tóibín, Carol Morley, Stephanie Zacharek, and Kogonada.”

Again, many thanks to Michael Hutchins for providing the film community with such a detailed breakdown of this major Blu-ray set. It’s saved this humble critic much time in gathering what would end up being (in the best possible scenario) the same information.

The visual quality of these films is indisputably grand. The individual restorations have been undertaken with the utmost of care in honor of the centennial birthday of Federico Fellini. Considering that many of these titles have only every been available through Criterion on DVD, the upgrades, though a very long time in coming, are absolutely worth it. The same holds true of each of the other discs. The work is simply stunning.

The shape of the box itself is a bone of contention to varying degrees among fans. While many, myself included, wish that a uniformity consistent with the shape of, say, Criterion’s monolithic Ingmar Bergman box set would’ve been maintained for this, Godzilla, and Agnes Varda, it’s also not worth one moment of ire. The box itself, about the size of a LP collection or an old thinner laserdisc box set, is a sturdy and colorful thing; tasteful yet delightfully gaudy in that somehow-attractive Fellini style. Considering the director’s origins as an illustrator with a flair for the fantastical, the beautifully robust renderings that adorn it are perfectly appropriate. The discs reside in individually labeled pockets within a hardbound folder within, which rests atop housing containing the two formidably bound paperback essay collection books.

*****

Be on the lookout for the second half of this film-by-film consideration of Essential Fellini in the weeks to come. In the meantime, may your days be lit with variety, may your nights work out better than those of Cabiria, and your life be eternally sweet.

Variety Lights

Director(s)

- Federico Fellini

- Alberto Lattuada

Writer(s)

- Federico Fellini (screenplay)

- Federico Fellini (story)

- Alberto Lattuada (screenplay)

- Tullio Pinelli (screenplay)

Cast

- Peppino De Filippo

- Carla Del Poggio

- Giulietta Masina

- John Kitzmiller

La Dolce Vita

Director(s)

- Federico Fellini

Writer(s)

- Federico Fellini (story)

- Ennio Flaiano (story)

- Tullio Pinelli (story)

- Federico Fellini (screenplay)

- Ennio Flaiano (screenplay)

- Tullio Pinelli (screenplay)

- Brunello Rondi (contributing writer)

Cast

- Marcello Mastroianni

- Anita Ekberg

- Anouk Aimée

- Yvonne Furneaux

Nights of Cabiria

Director(s)

- Federico Fellini

Writer(s)

- Federico Fellini (story)

- Ennio Flaiano (story)

- Tullio Pinelli (story)

- Federico Fellini (screenplay)

- Ennio Flaiano (screenplay)

- Tullio Pinelli (screenplay)

- Pier Paolo Pasolini (collaboration)

Cast

- Giulietta Masina

- François Périer

- Franca Marzi

- Dorian Gray

La Strada

Director(s)

- Federico Fellini

Writer(s)

- Federico Fellini (story and screenplay)

- Tullio Pinelli (story and screenplay)

- Tullio Pinelli (dialogue)

- Ennio Flaiano (screenplay collaborator)

Cast

- Anthony Quinn

- Giulietta Masina

- Richard Basehart

- Aldo Silvani

Il Bidone

Director(s)

- Federico Fellini

Writer(s)

- Federico Fellini

- Ennio Flaiano

- Tullio Pinelli

Cast

- Broderick Crawford

- Giulietta Masina

- Richard Basehart

- Franco Fabrizi

I Vitelloni

Director(s)

- Federico Fellini

Writer(s)

- Federico Fellini (story)

- Ennio Flaiano (story)

- Tullio Pinelli (story)

- Federico Fellini (screenplay)

- Ennio Flaiano (screenplay)

Cast

- Franco Interlenghi

- Alberto Sordi

- Franco Fabrizi

- Leopoldo Trieste

The White Sheik

Director(s)

- Federico Fellini

Writer(s)

- Michelangelo Antonioni (story)

- Federico Fellini (story)

- Tullio Pinelli (story)

- Federico Fellini (screenplay)

- Tullio Pinelli (screenplay)

- Ennio Flaiano (collaborator on screenplay)

Cast

- Alberto Sordi

- Brunella Bovo

- Leopoldo Trieste

- Giulietta Masina