Blu-ray Review: Criterion's MARTIN SCORSESE'S WORLD CINEMA PROJECT VOL. 3 Defies Borders

Martin Scorsese and George Lucas further the cause of film restoration with six newly-released international titles.

In the absence of martial arts, giant monsters, balletic gunplay, or blatantly exploitative line-crossing content, the notion of watching films from different countries and/or cultures quickly crosses the border into “work” for more people than might ever admit to it.

Such films tend to be unblinkingly dramatic if not outwardly political in their attempts to cinematically explore their own cultures, histories, or national identities. The mirrors that are held up by the filmmakers are often dirty, grimy, even cracked. (And that’s per directorial intent- before the entropic degradation that so often physically plagues surviving prints over time).

Yet, even as genre has eaten into everything (including our attention spans and capacity for cultural curiosity) America’s Greatest Living Auteur (TM) Martin Scorsese is here to remind us that there’s more to the art of film than popcorn fare and cheap thrills. Sometimes, a healthy serving of “cinematic vegetables” is just the thing to recalibrate our equilibrium of the soul. And, his “movie brat” cohort George Lucas wholeheartedly agrees. (For more on that, see the Pixote section of this write-up).

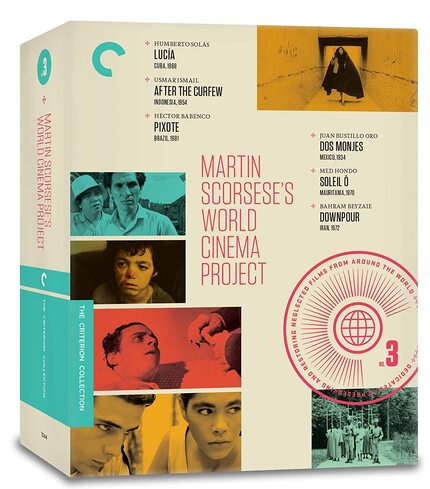

So how excited should be for the third entry in Criterion’s intermittent World Cinema Project series? Utilizing the heroic salvage and restoration work of Scorsese’s Film Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting and preserving motion picture history (its own self-description), Criterion has made a practice, as semi-regular it may be (Volume One came in late 2013, Volume Two in May 2017, and Volume Three now), of packaging an arbitrary half-dozen of these films together for convenient acquisition. (Volume Three is available as part of Criterion's 50% off sale, though only today, October 20, 2020.) This time we get:

Lucía (Cuba, Humberto Solás, 1968)

After the Curfew (Indonesia, Usmar Ismail, 1954)

Pixote (Brazil, Héctor Babenco, 1981)

Soleil Ô (Mauritania, Med Hondo, 1970)

Dos monjes (Mexico, Juan Bustillo Oro, 1934)

Downpour (Iran, Bahram Beyzaie, 1972)

Though there’s not an undeserving dud among them, they are, in the eye of this beholder at least, something of a mixed helping. Just how mixed? Read on, as each film is briefly considered...

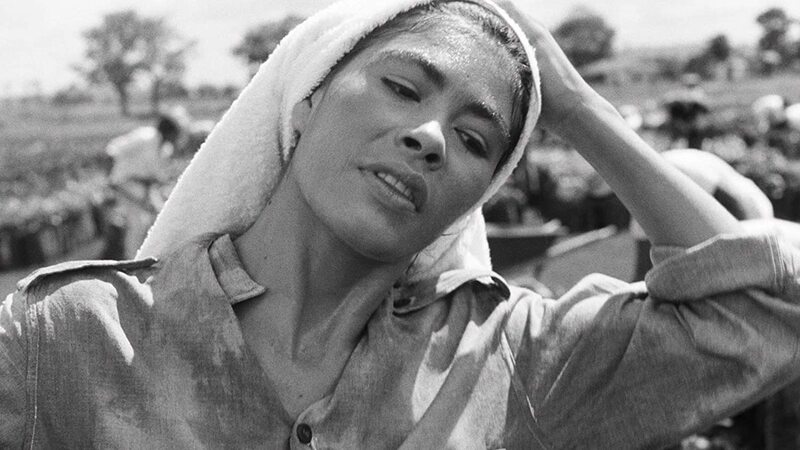

LUCÍA

As expansive and ambitious as it is off-putting and unpleasant, Humberto Solás 1968 epic of Cuban revolution spans not just history, but film styles and genres. Broken into three separate black-and-white stories, each told via a varied cinematic idiom, Lucía makes its connections through political underlining as experienced by three unrelated women whom each bear the title moniker.

Of course, the female perspective stops short at Solás himself, who directed and also wrote the bold picture. His decision to wrap Lucía up as a “women’s picture” (to utilize an Old Hollywood genre that had drifted away, even then) is clearly rooted not in notions of feminist strength and collectivity but in the vulnerability and victimhood of women. By depicting their plights amid revolution, he would tout revolution all the more loudly.

Out of the gate, Lucía makes it clear that this journey will not be a tempered one. The first of the three segments takes place circa the 1898 Cuban war of independence, aka the Spanish-American War- an eight-week conflict that resulted not only in Spain relinquishing Cuba, but also another war elsewhere (the Philippine-American War). Shot in increasingly stark, extreme tones, the segment takes on a stomach-churning quality as a supposedly spicy story being told among a gathering of women becomes about the random and brutal rape of nuns. We experience the story as full-on abstract horror, complete with a shrill atonal score, through the mind’s eye of 1898 Lucía (Raquel Revuelta).

The subsequent two segments do not tread anywhere near the assaulting tonality of the first one, though Solás has set the stage accordingly. The second part, starring Eslinda Núñez as 1930s Lucía, takes place during the mounting unrest of the Gerardo Machado regime. As Machado’s popularity gives way to dictatorial practice, Lucía, like many a woman, finds herself caught in the middle of it. It plays out like something of a gangster film, albeit one that that’s going on in the periphery of our heroine’s day-to-day life. Untouchables-esque machine gun ambushes in public places abound as women and children flee screaming for their lives.

The third and final segment is a lighter-by-comparison domestic drama that is roughly contemporary with when the film was made. (Onscreen it leaves the exact year indeterminate, “196_”). The Lucía of this age is an initially blissful newlywed who learns more quickly than not that her spouse, Tomas (Adolfo Llauradó) doesn’t grant much of a blissful situation. Despite his staunch claims to Castro’s proletariat revolution, the guy is a festering chauvinist. (A depiction that could be read as an early in-house critique of Castro’s described totalitarianism). When the powers-that-be dispatch a fresh-faced young reading instructor to their home to address Lucía’s illiteracy, Tomas doubles down, keeping her home and wanting this guy out. While it’s debatable that she was ever attracted to the instructor before Tomas got all puffy about him, he does inevitably begin to appear as a viable alternative to her. Mainly though, the instructor literally instructs her to free herself from her husband. Will she? Can she?

As presented here in impressive 1080p, Lucía is a particularly stunning visual discovery. Beyond that, for those not quite on its wavelength, it can prove to be something of an arthouse slog. Still though, it’s a historical triptych to behold, particularly the unsettling and viscerally challenging first segment.

AFTER THE CURFEW

Within the first minutes of Usmar Ismail’s 1954 grabber After the Curfew (Lewat Djam Malam) one might be wondering, is this a Film Noir? A crime film? A political screed? A postwar drama? Or a tortured romance? It is, of course, all of the above- to varying degrees. A curious if uneasy blend, to be sure.

Iskandar (A.N. Alcaff), having just been released from active combat service in the Indonesian Armed Forces, arrives home to a happy family and fiancée (Netty Herawaty). There’s a job and a completely reasonable middle-class life just sitting there waiting for him. But his psyche is tortured from the horrors of war. Post-traumatic stress quickly leads Iskandar down a dark path of seeking out former military acquaintances. Instead of closure, he gets drawn into a slow, violent maelstrom.

Generally regarded as the first Indonesian film to embrace personal vision with a viable message, After the Curfew resonates as a living relic of its time and place. Moody black and white but not necessarily atmospheric, the film nevertheless takes viewers into its oddly suburban milieu and lurking postwar disquiet. It’s not a standout inclusion in Criterion’s WCP3 (no entries are unappreciated), though it is an effective watch that cultivates universal tension amid its very specific political and cultural circumstances.

PIXOTE

In the unauthorized George Lucas autobiography Skywalking, author Dale Pollock recounts that circa 1981, his subject was skittish about bankrolling Lawrence Kasdan’s hard R-rated directorial debut Body Heat, for fear that the man behind the kid-friendly Star Wars series be looked upon as a purveyor of sexual content. How things have since changed...

In his brief introduction to the altogether harrowing Brazilian film Pixote (also from 1981), Martin Scorsese mentions that the film’s restoration- I hesitate to use the term “immaculate” per the film’s own centric wallowing in the grimy realities of economically depressed actualities of its own world (São Paulo circa 1981, to be exact), though it is that good- was made possible by the philanthropic George Lucas Family Foundation. (The same foundation also bankrolled a number of other Film Foundation restorations, as well. This one, though, is given particular recognition by Scorsese).

It is perhaps challenging to reconcile Lucas’s key involvement with saving a film as confrontationally violent and disturbing as Pixote- its street-real content rendered all the more unsettling by the fact that it is both perpetrated by and inflicted upon its cast of underage boys. Director Héctor Babenco doesn’t skimp on nor shy away from full-on, straightforward depictions of the adolescent and teenage unrest of the forgotten youths of the film, the ten-year-old Pixote (the late highly evocative non-actor Fernando Ramos da Silva) taking a good brunt of it.

In the instances of box sets such as the World Cinema Project offerings, it is quite fair to view a particular film as a kind of centerpiece; the one that might’ve served the label just as well if not better had it been released as a stand-alone disc. For this set, Pixote (aka Pixote: a Lei do Mais Fraco) is that film. Though very difficult, what with its brown-water-and-blood commodes, its filth-addled depiction of authoritarian prison-like buildings for displaced kids, and violence both physical and emotional, Babenco earns every moment of this unflinching realism, something he observed in his shut-down attempt to make a documentary about a the subject.

The São Paulo of Pixote is a kind of always-night cesspool of survival-moded dregs of society. Sex workers, drug pushers, runaways, deviants, rapists- outcasts of all shapes, hues, and sizes, though nearly all of them underage. The eye that the film turns to all of them is anything but blind, though never sentimental, either. You win nothing but a most resonant gut-punch for making it though the whole of Pixote- a cold-bodied reminder that corners of our world are anything but kid-friendly... even when it traps and snares said kids.

DOS MONJES

Gloriously awash in baroque minimalism and shadow and light but mostly shadow, we have the 1934 Mexican film Dos monjes (Two Monks). The fact that the film, itself a humble three-hander love triangle gone sideways, is more expressionist than some German expressionism that preceded it a decade earlier is no coincidence.

Film scholar Charles Ramírez Berg, in the film’s bonus featurette, explains that the film’s visionary director, Juan Bustillo Oro, was an obsessive cinephile, eager to try his hand at depicting the psychological physicality of Murnau, Wiene, and Lang. (Not to mention the American horror adaptations of Frankenstein, Dracula and others that were coming out of Universal at the time). With the expert help of avant-garde photographer Agustín Jiménez behind the camera, Oro succeeds in creating a very special dreamscape of a film.

But Dos monjes is noteworthy beyond its crooked atmosphere and oneiric black and white cinematography. Narratively, the film commits to the very unique decision of telling its core flashback story in full twice, once from the perspective of each of the two male protagonists (Juan and Javier, played by Víctor Urruchúa and Carlos Villatoro). They are each, of course, the hero of their own version, though neither is without truths in his perspective. Indeed, as it’s pointed out at every option, before there was Kurosawa’s Rashomon, there was the enigmatic and alluring Dos monjes. The eighty-five-minute film resonates as one of WCP3’s greatest revelations.

SOLEIL Ô

In a moment in time when justified black rage is nothing new, it’s good to be reminded of the expansive history of the racism behind it, in all of its deplorable skins. Whether institutional, ingrained, blatantly plain-spoken, or delivered by fists and fire, the rejection of the black African in westernized countries is a long-running and hideously shameful thing.

Both on-the-nose and abstract, filmmaker Med Hondo’s Soleil Ô (Oh, Sun) operates in a kind of First World no man’s land; a place where the city at large looks upon those it considers “others” with polite distain. For most of Hondo’s Paris, acceptance of darker-skinned immigrants extends only in theory. Our able-bodied and eager-to-work West African protagonist (Robert Liensol) spends much time immediately being refused employment, then wandering the streets ruminating on why. These narrated internal monologues are Hondo’s method of unambiguously unpacking the racial injustice at hand:

“We former, present and future colonized people have contributed greatly to the foundation of your industrial and economic capital. Should the interest on that capital not be our right? So please don’t say that we’re costing you dearly. Furthermore, the help that you are giving us is aimed above all at preserving your own markets and maintaining your economic privileges.”

Before the end of this valiantly scraped-together black-and-white experimental 1970 effort (check out those fleeting moments of animation!), our unnamed protagonist mentally levies his assessment of brokenness upon Paris (and by extension, the western world): “You are branded by Western civilization. You think ‘white’.” Earlier this summer, The New York Times saw fit to level that basic accusation upon Criterion itself. While not unwarranted in terms of the racial metrics of the company’s output, curating box sets such as this which give unwavering voice to directors such as Hondo is nothing to sneeze at. Even as not all of Soleil Ô proves gripping, its scrappiness is a badge of honor, and its bold truth-saying remains terribly relevant.

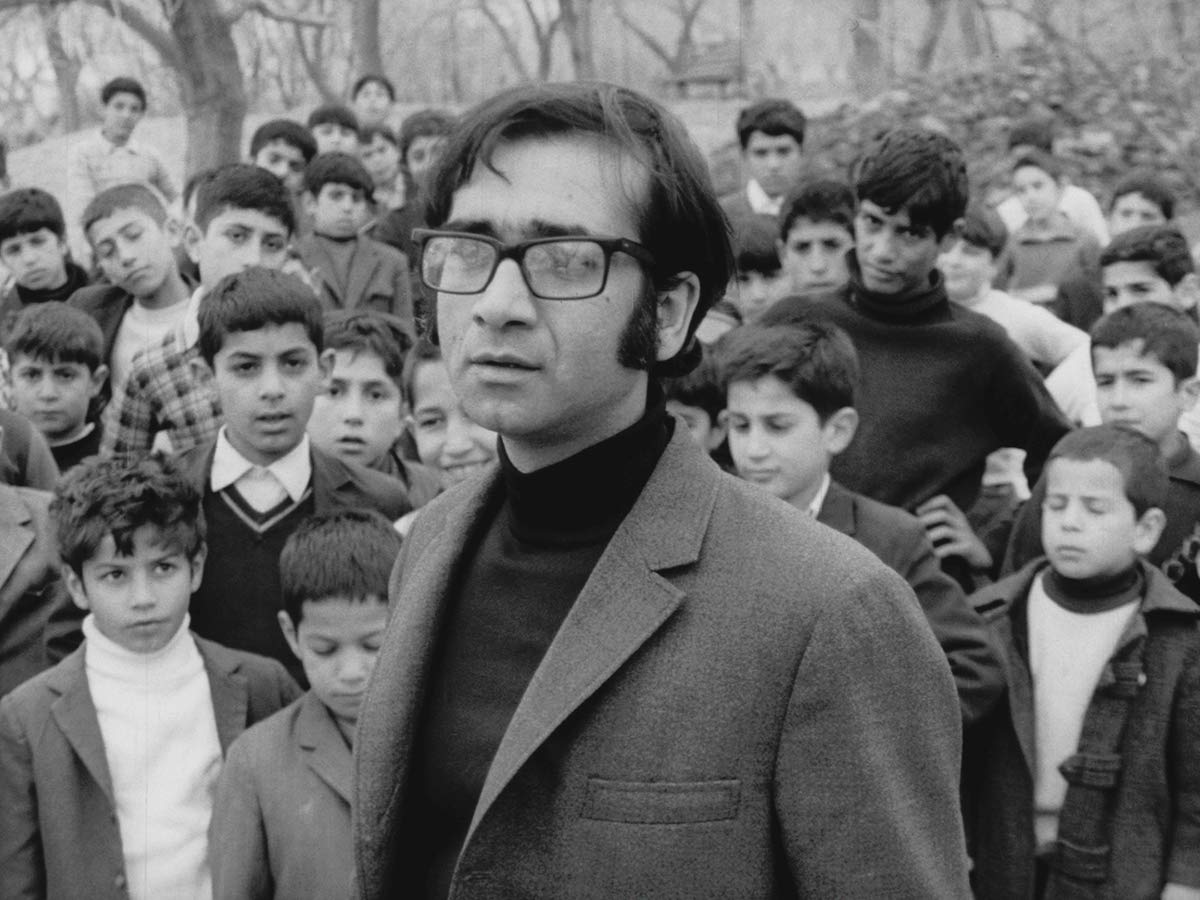

DOWNPOUR

At the very forefront of “the revolutionary cinema of Iran” was Bahram Beyzaie’s 1972 Downpour (Ragbar; رگبار ). Beyzaie, in his recently recorded thirty-minute supplementary interview for this release, talks about how Downpour was his response to what he calls the “vulgar” state of commercial Iranian cinema at the time. Even still, of all the films in this set, Downpour might be the post conventionally enjoyable. Though a lovingly ramshackle affair- the film is no-frills black-and-white, assembled in a manner that resembles the compelling inexactitude of early George Romero cinema- the plot hinges on a very traditional love triangle.

The late Parviz Fannizadeh plays nebbish everyman Hekmati, a mirror vendor turned schoolteacher who becomes smitten with the beautiful Atefeh (Parvaneh Massoumi), a young woman he sees on the street. The problem is that Atefeh is already engaged to the big and brutish Rahim (Manuchehr Farid), who’s apparent wealth is enough to ensure her a secure if thoroughly unhappy life. Hekmati, of course, can’t compete with Rahim in any way, except that he’s not a mustachioed self-important bullying jerk. For a time, the film’s love dynamic has all the nuance of a Fleischer Studios Popeye cartoon, sans spinach. In time, the film will also evoke the later and considerably more Australian Crocodile Dundee not once but twice.

Downpour, though conventionally enjoyable, is not to be dismissed as frivolous. Beyzaie tells the story not as a romance but as a socially conscious melancholy comedy of sorts. Between the gaping seams, one can see the confidence that the filmmaker has imbued in every aspect of this, his first film. Leading man Fannizadeh is owed much in its success, as he renders his lonely underdog educator as fully sympathetic every step of the way.

The restoration on this film is a miracle unto itself, as this is one of those Film Foundation rescues in which the last known print is all that was available to work with. Consequently, there are burned-in English subtitles that cannot be turned off, as they are part of the original element. This, though, is an easy price to pay to have Downpour beautifully recovered. Satisfying heartache and humor await anyone who opts to venture into this rundown area of provincial Iran.

*****

Criterion is once again utilizing the World Cinema Project series as the last bastion of its long-abandoned dual format packaging. Though Volume One came about in the midst of this line-wide phase of twined DVDs and Blu-ray sharing the same fat package, both subsequent volumes arrived well after that ship had sailed. Fortunately for those of us who appreciate uniformity on our physical media shelves, these sets are where the memory lives on. And, seeing how the DVD format conquered the globe while the far superior Blu-ray never enjoyed the same foothold, perhaps this series is just the place for Criterion’s dual format aesthetic to persevere.

This third volume of Martin Scorsese’s World Film Project serves up a refreshingly diverse array of films from the “Third World”. The work of the Film Foundation is, as always, heroically immaculate and worthy of our support. Collecting these sets is certainly a viable way to vindicate the tireless restoration and recovery work being done. An added perk is that these cinematic vegetables make for a particularly tasty and boundaries-expanding mixed helping.

Here are the bonuses and bullet-points for this box set:

• New, restored 4K digital transfers of all six films, overseen by the World Cinema Project in collaboration with the Cineteca di Bologna, with uncompressed monaural soundtracks on the Blu-rays.

• New introductions to the films by World Cinema Project founder Martin Scorsese.

• New interviews featuring Downpour director Bahram Beyzaie, film scholar Charles Ramírez Berg (on Dos monjes), and journalist J. B. Kristanto (on After the Curfew).

• Excerpts from a 2016 interview with Pixote director Héctor Babenco and a 2018 interview with Soleil Ô director Med Hondo.

• Humberto & “Lucía,” a 2020 documentary short by Carlos Barba Salva featuring Lucía director Humberto Solás and members of his cast and crew.

• Prologue for the U.S. release of Pixote, created by Babenco.

• New English subtitle translations.

• PLUS: A booklet featuring an introduction by Cecilia Cenciarelli, head of research and international projects for the Cineteca di Bologna, and essays by critics and scholars Dennis Lim, Adrian Jonathan Pasaribu, Stephanie Dennison, Elisa Lozano, Aboubakar Sanogo, and Hamid Naficy.

Oh, Sun

Director(s)

- Med Hondo

Writer(s)

- Med Hondo

Cast

- Robert Liensol

- Théo Légitimus

- Gabriel Glissant

- Mabousso Lo

Two Monks

Director(s)

- Juan Bustillo Oro

Writer(s)

- Juan Bustillo Oro

- José Manuel Cordero

Cast

- Víctor Urruchúa

- Carlos Villatoro

- Magda Haller

- Beltrán de Heredia

Luc�a

Director(s)

- Humberto Solás

Writer(s)

- Julio García Espinosa

- Nelson Rodríguez

- Humberto Solás

Cast

- Raquel Revuelta

- Eslinda Núñez

- Adela Legrá

- Eduardo Moure

Pixote

Director(s)

- Hector Babenco

Writer(s)

- Hector Babenco (story)

- Jorge Durán (story)

- Hector Babenco (screenplay)

- Jorge Durán (screenplay)

- José Louzeiro (book)

Cast

- Fernando Ramos da Silva

- Jorge Julião

- Gilberto Moura

- Edilson Lino

After the Curfew

Director(s)

- Usmar Ismail

Writer(s)

- Asrul Sani

Cast

- A.N. Alcaff

- Dhalia

- Netty Herawati

- Bambang Hermanto

Ragbar

Director(s)

- Bahram Beizai

Writer(s)

- Bahram Beizai

Cast

- Parviz Fanizadeh

- Mohamad Ali Keshavarz

- Jamshid Layegh

- Parvaneh Massoumi