Review: DIETRICH & VON STERNBERG IN HOLLYWOOD on Criterion Blu-ray

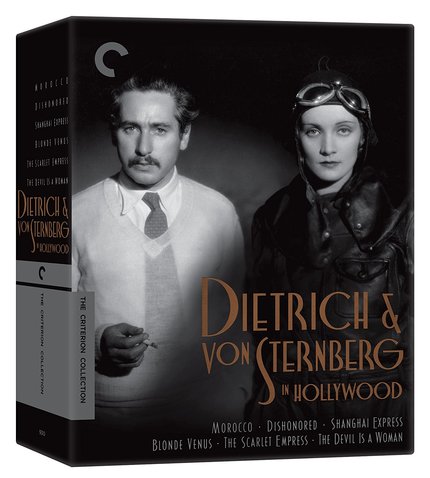

Criterion's definitive collection of Josef von Sternberg's Hollywood films starring Marlene Dietrich beguiles.

"Shadow is mystery and light is clarity. Shadow conceals, light reveals. To know what to reveal and what to conceal and then what degree and how to do this is all there is to art."

- Josef von Sternberg

In the art and history of filmmaking, few director/actress pairings struck the resonant chord and demonstrated the undeniable give-and-take chemistry of Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich.

Their seven-film collaboration, spanning eight years and an ocean, is the stuff of movie legend: An artiste director sculpts a siren; the siren ascends to becoming a goddess; the artiste is left behind, forgotten. From 1929 to 1935, this arc would play out; beginning in Germany and fly high through pre-code Hollywood, before finally being tempered, then suddenly extinguished.

Nothing short of one of the most arch filmmakers of all time, von Sternberg operated via what was then described as a distinctly “European sensibility.” In other words, style over plot; light, shadow and setting over logic, factuality, and reason. While not an experimental filmmaker in the surrealist sense (a movement von Sternberg must have no doubt bumped up against in this time), his films exhibit just enough narrative drive to convince moviegoers that the plot might actually matter.

To someone at some point in the production mill, it might have. (To writers, studio executives, etc.). But not to von Sternberg. In his prime -- the very era represented in this beautiful, lavish and essential six-disc Criterion box -- everyone and everything on his sets were his props and pawns. In terms of tight-fisted, near-impossible control down to every last literal detail, von Sternberg was the Michael Mann of his day.

Never were his painterly priorities more engaging or well-matched than when he applied them to his starlet and muse, German ingenue Marlene Dietrich. Luminous and lascivious, independent and intriguing was she. Dietrich, as crafted by herself and von Sternberg with über-intentionality, was put forth as an enigma of brokenness, her inner-radiance bleeding through the cracks of her soul; a new feminine mystique in the Garbo-ruled age of feminine mystique redux.

To many, both male and female, this version of Dietrich would prove irresistible. She would maintain a persona of ever deliberate adriftness; content to be utterly, emotionally untethered. A “fallen woman” who nevertheless lives by her own rules. Yet, her heart would break.

This is Marlene Dietrich as rendered by Josef von Sternberg. And no one else.

*****

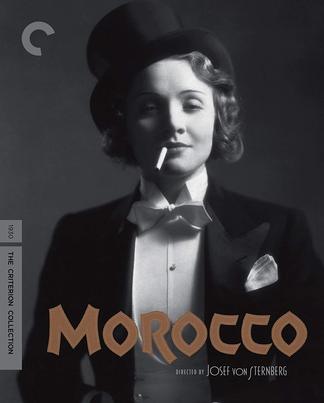

Morocco (1930)

“There’s a hundred ways to die, brother... and I’m going to pick my own!”

So boasts a cocksure Gary Cooper in 1930’s Morocco, the Hollywood premier of star Marlene Dietrich and Director Josef von Sternberg. Cooper, top billed as Foreign Legionnaire Tom Brown, foolishly believed himself to be the true star of the film; his co-star Dietrich merely “the girl”. Though Cooper was portraying a serial playboy and perpetually cool “drink of water” in this picture, in the eyes of both his director and the audience, he was “the girl”. It wouldn’t be the last time, either. (For an even more overt example, check out Lubisch’s 1933’s Design for Living, in which Cooper ends up one of the two male partners in a committed three-way relationship with Miriam Hopkins). Though Cooper would land on his feet, the legacy of the fantastic film Morocco belongs to Dietrich.

As cabaret singer Amy Jolly (whom, according to a bonus feature on the disc, was apparently a real person, who knew?), Dietrich takes all of Morocco, with an apparent sensual ease that is all hers. Never mind the actual country; this soundstaged version of the desert locale, realized in exquisite detail, just as any respectable von Sternberg set would be, is all Dietrich needed to show the world that she is in fact her own special kind of star, and not “the next Garbo”.

Following in the footsteps of the German-produced The Blue Angel, Morocco is the second Dietrich/von Sternberg collaboration, and their first of six in Hollywood. Of those six, it is the most salacious, and the strongest. While Dietrich’s electric steaminess is undeniable in this picture, von Sternberg’s managing of his own narrative tasks is well balanced with his own drive to decorate, light, sculpt, and wallow in his own on-screen world, in this case a recreated Morocco. Everyone is particularly “in the zone” here.

That said, anyone looking to make the point back then that pre-code cinema is too sexually obsessed for its own good need look no further than Morocco, with its brilliantly androgynous cabaret number (complete with Dietrich planting a smooch on a woman in the audience), and its nonstop fixation with sexual conquest. In the end, heartfelt devotion will prevail, as our heroine follows her beloved’s traveling regiment blindly into the desert, shedding her high heels on the way. The symbolism of that gesture can and will continue to be debated, but the greatness of Morocco- the one that started it all for Dietrich and von Sternberg in Hollywood- never will be.

*****

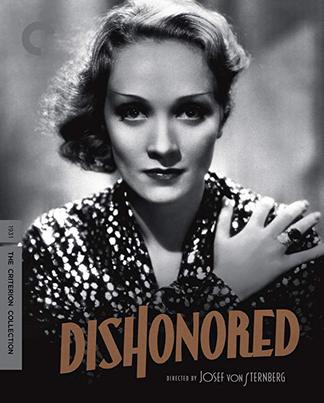

Dishonored (1931)

In the spy thriller, Dishonored, von Sternberg continued to push Dietrich’s cold aloof qualities in tantalizing new ways. As the slippery Austrian spy X-27, she matches more than wits with a Russian colonel played by future John Ford favorite, Victor McLagen.

Predating his Oscar win for 1936’s The Informant, this is McLagen as a dashing leading man, many years before Ford played him up as a boorish second banana to John Wayne in his Cavalry trilogy. In Dishonored, however, he seems all too happy to fall in line as second banana to rapidly rising star Dietrich.

Dietrich’s trademark Devil-may-care attitude makes her a perfect fit for this role as the most skilled and dangerous of spies. In actuality, she is very patriotic (hence her personal sacrifices for her country), and therefore faced with her greatest conflict- her love for McLagen’s character. She could have been the greatest spy the world has ever known- so the opening title card tells us- were it not for the fact that she’s a woman!

Clearly, cutting edge as these films were in some respects, trouncing the notion that a woman is a slave to her heart wasn’t on the feminist agenda just yet. Nor was disavowing the assumption that a female spy’s weapon on choice is her body.

Cross dissolving in and out of a brief moment of shots we’d experienced just minutes prior, von Sternberg is trying his hand, quite liberally in this movie, at fragmented memory realization. The technique may strike some as a pure throwback to his not-that-long-prior silent filmmaking days. There is, however, nothing at all wrong with that. The resolution of Dishonored, however... that doesn’t get off the hook so easily.

The only title of the bunch that today would be considered “genre”, Dishonored is a decently indecent spy thriller, and an even better Dietrich/von Sternberg entry. Still early in their ongoing collaboration, there’s room for improvement, yes. But it’s a worthy inclusion, all the same.

*****

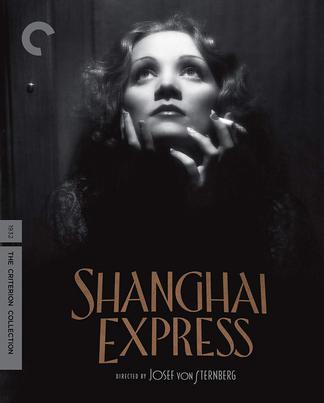

Shanghai Express (1931)

The same year, we also got Shanghai Express, an eighty-two minute train ride across contemporary China rife with barely-comprehensible intrigue and a continuous barrage of ornately busy visuals. A passenger train complete with sliding glass doors and lavish interior is the dominant setting. China’s then-colonialist division justifies the array of diverse accents and ethnicities in this warped, artificial version of the real thing. Like all of these films, Shanghai Express is a total Hollywood studio-based shoot. Though engaging in racial stereotypes and outright fictions about China, von Sternberg probably employed every actor, extra (and then some) of Chinese descent. Though the whole thing is culturally suspect by today’s standards, it’s interesting to think that back then, mounting a film like this one in this manner would seem downright progressive.

The enigmatic actress Anna May Wong plays a Chinese match for Dietrich, their characters quickly bonding as travelled women of ill repute. Wong comes closer than anyone else at stealing a film out from under Dietrich, though not quite succeeding. This is only thanks to a few downright indelible shots of Dietrich that von Sternberg cooks up. Here we have the immortal image of the star, bathed in haze and enigma, smoking a lonely cigarette in close-up while gazing upward. It alone is enough to anchor Shanghai Express in terms of classic stature, and cement the myth-making of Dietrich/von Sternberg.

The movie itself is a fair potboiler, but one doesn’t board this train for the plot, nor for its destination. It’s the journey and the scenery that are everything. Those, and of course the company of fellow travelers.

*****

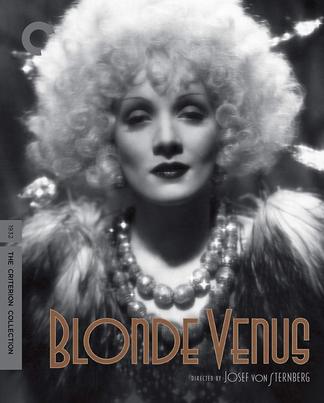

Blonde Venus (1932)

“I dress for the image. Not for myself, not for the public, not for fashion, not for men.”

- Marlene Dietrich

The increasingly obsessive eye of Josef von Sternberg wasn’t the only one behind the scenes with a fixation for Marlene Dietrich. Travis Banton, Paramount’s legendary costume designer of this era, also found a powerful muse in the actress. She proved to be Barton’s canvas as he worked his palate of exquisite fabrics and unexpected outfits.

In Blonde Venus, the fourth film in this set- and one of the most famous- is a testament to Barton’s talent. Even at her lowest point in this morally messy movie, Dietrich appears ravishing. Although a juggernaut of screen appeal out of the gate, by this point she has unquestionably honed her persona into constant camera catnip.

It must be said, though, that in playing a popular cabaret singer, Dietrich’s onstage moments are the film’s most breathtaking portions. Whether starting out in a gorilla suit as part of a (decidedly not politically correct) jungle native revue (a bit Joel Schumacher swiped for his 1997 train-wreck Batman and Robin), or reprising her top hat and tails routine from Morocco (now with a glittery tux), it is clear that she and she alone rules the stage of the era, wherever she goes.

Blonde Venus is the first of these films to make any attempt at domesticating Dietrich. In the film, she plays Helen, the stay-at-home wife of a scientist in failing health (Herbert Marshall) and the mother of their young son, Johnny (Dickie Moore). In order to afford the medical attention her husband requires, she goes back to her former cabaret profession- one she once dominated, but all too happily escaped in favor of domesticity.

Once back in, Helen meets a swanky and irresistible millionaire played by Cary Grant. While her husband is overseas for many months getting his operation, Helen finds herself in a full-blown affair with this new guy. Things quickly go south on all fronts when her husband returns home to find that no one has obviously been living there for months. Dietrich finds herself on the road with her boy, headlining gigs wherever she can while he bides his time in motel rooms, or wherever.

It’s all rather trashy, with Dietrich’s Helen riding a see-saw of being rich and being poor and being rich and being poor, all the while looking great, carrying on torrid affairs, and detaching from everything but her boy. Only Dietrich could manage to make such a willfully self-destructive character as sympathetic a figure as she is.

Although in many ways she’s arrived at this point through her own series of bad choices, by the time her husband demands their son back, it’s he who strikes the viewer as the problem. This in itself is a pretty remarkable feat for both the filmmaker and particularly the actress. All the while, von Sternberg continues to craft a bigger and more expansive sensory world for her to have her way with. And, though some of the sharp edges of their past films have been filed down this time, Dietrich does indeed have her way with it.

*****

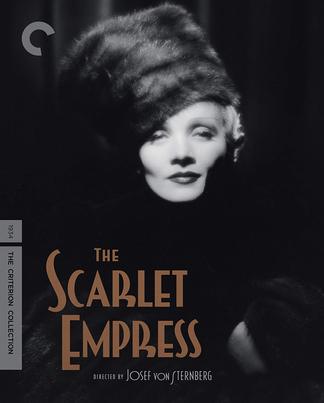

The Scarlet Empress (1934)

The Scarlet Empress, then, promptly resets her back to girly mode, at least for a while. Von Sternberg’s great Grand Guignol period piece finds Dietrich as humble royalty (Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, to be precise), happily flouncing and trouncing through her home castle in Pomerania, Prussia.

Then one day, a dashing envoy, Count Alexie (John Lodge) arrives on behalf of Empress Elizabeth of Russia (played domineeringly by Louise Dresser). The party has come to whisk Sophie off to their frigid motherland. There, she will marry the future Tzar, Peter III (Sam Jaffe).

Upon arrival, Sophie is promptly renamed Catherine, and told in no uncertain terms that her sole purposes to give birth to a son, a rightful heir to the throne of Russia. And what a throne it is- a massive stone-carved lake bird with wings spread wide and its neck looped around. This throne resembles something out of a 1970’s Queen album cover made sit-able. It’s a perfect match for the many, many eerie stone figures placed all over the castle. In the history of film, if also certainly in the history of history, one would be hard pressed to find a more bountifully baroque palace.

In von Sternberg’s Russia, no individual of focus isn’t foregrounded by a flag, or some mesh, or part of a strange statue, or Rublev-esque religious illustrations, or just good old fashioned poles or candle sticks. This is so often the case in all of these films, but this time... it’s nothing short of breathtaking. And also, in its stoney splendor, exhausting. Completely palace-bound, there’s a righteously suffocating sensation about The Scarlet Empress.

The wardrobe is elaborate to the hilt, right on up to the impeccably fuzzy hats. (Travis Banton again, unleashed). There are at least too many people by one-third in at any given royal gathering scene, ornately jamming the frame from all sides with their fancy hair, their hoop dresses, their military accoutrements, their precision placements, the decor and the decorum. This is the filmmaker at the height of his powers, truly cut loose and untethered from the reality of the story he’s chosen to depict and any studio-mandated boundaries. May horses clop over those things, twice each day and once again on Sunday!!

True, the real-life Catherine the Great’s coup to take the throne and her subsequent decades-long reign were violent and awash with horrors, but never mind that here. In The Scarlet Empress- the last pre-Code film of the batch- Dietrich’s Catherine deviously and freely sleeps her way into the graces of the palace guard, enabling her to, after being forced into subservient baby-making for much of the picture, lash out in a glorious coup of feminist vengeance. Pay no heed to the fact that within the actual Peter III’s six-month reign, he proved to be one of Russia’s most socially progressive Emperors. Here, he is a Joker-faced monster to be rightly dispatched.

As the only title in this set to have been previously released by Criterion on DVD, The Scarlet Empress is a most welcome upgrade in the collection. While von Sternberg’s run-amok artistry and auteur power is said to have generally been an anguish-inducing freight train of ego for all other cast and crew involved, there’s no denying the majesty of what we’ve got here. The Scarlet Empress is at once both out of its mind and one for the books. Just, not the proper Russian history books.

*****

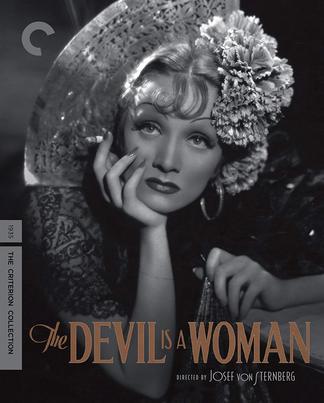

The Devil is a Woman (1935)

If The Scarlet Empress is peak Dietrich/von Sternberg, 1935’s The Devil Is a Woman is the inevitable decline. Though the film itself remains a visual treasure trove, and is absolutely worthy of inclusion with the previous five, external and internal factors were piling up to nullify it by comparison, and, more broadly, bring this majestic chapter of film history to a close.

The Devil Is a Woman has the wicked distinction of being both directed and photographed by von Sternberg. The result is a mise-en-scéne so dense in its fetish for detail, the story is all but suffocated. By this point it’s obvious that von Sternberg never saw a large wicker cage that he didn’t position in the foreground in one of his exotic locales. Not to mention the ubiquitous sheer curtains, plaster textures, and in party scenes, streamers, streamers, streamers... Streamers choking whatever oxygen remained in the frame right out.

“Kiss me .. and I'll break your heart!”, went the tagline for the Production Code-approved, Spanish-set (but still, as always, Hollywood sets) The Devil Is a Woman. Men say the darnedest things when they’re talking to each other, particularly about specific women to avoid, and why to avoid them. Primarily an older man’s flashback (the older man played by Lionel Atwill) as he warns a younger man (Cesar Romero) not to get entangled with the likes of the sexy Concha Perez (Dietrich), as he did. Oh the toil, oh the humiliation! Don’t do it son, just don’t do it.

But he does it. Not only has he not heeded the advice of the older man, he’s missed the tagline as well. It’s passable trash, sure, but brilliantly realized by von Sternberg, said to have been doing much of the work off camera literally himself. There is something of a twist, but the primary takeaways from The Devil Is a Woman are how Dietrich wears a ruffly flamenco dress, and her newly arched eyebrows. By this time, the actress/director duo had completely crossed the line of what many now consider to be high camp. Not intentionally, of course. But from, let’s say, Blonde Venus onward, the sensibility could easily be made to fit that kind of pigeonhole. The Devil Is a Woman is not work avoiding, even though it’s no one’s best work, and does struggle at times to find its own pulse.

And yet, somehow, it’s exhilarating. To think that von Sternberg was single-handedly pulling the strings on productions such as this, at this time in Hollywood, is staggering. For this critic, the “early talkie” era all too often yields cinema endurance tests; likely due to the sudden lack of camera mobility and lack of music scores. The six films of this set suffer no such common troubles.

*****

Further complicating this, though, is the state of things in 1935 Hollywood, as the Production Code buckled up. Pushover William Hayes brought in Joseph Breen to strictly enforce the half-ignored existing rules regarding morality in movies. And poof, the party was over. The trademark sauciness of so many motion pictures, particularly the Dietrich/von Sternberg releases, suddenly had to be quelled. Just like that, Breen had poured cold milk into their rich Tabasco.

Beyond Breen, though, the star/director partnership was fraying on its own. The thing about movies, whether one is making them or seeing them, they end. So too did the magnificent Dietrich/von Sternberg run at Paramount. With the notoriously difficult von Sternberg suddenly fallen from all favor, the Euro-auteur was unceremoniously run out of the studio- never to fully land on his feet again.

As is pointed out on several of the bonus features scattered across the six discs, it turns out that Dietrich did not need him to continue thriving; though the opposite certainly seemed to be proven true. And, although Dietrich’s movie career flourished for several more decades, with she herself (per legend) ordering her own lighting just so, she never again achieved the otherworldly indelible von Sternberg-ian look again.

In later years, she frequently acknowledged as much, often citing von Sternberg as “the man who made me”. In a certain respect, the inverse could be said to be true in von Sternberg’s case, though him without her ended up adding up to far, far less than her without him. Von Sternberg wouldn’t work with Dietrich ever again, and would scarcely ever again make another memorable movie moment. His wad truly shot and his bridges sufficiently burnt in the process, home studio Paramount and the filmgoing public were, for better or for worse, ready to be done with him.

Thankfully, all these years later, Criterion feels the opposite. Their high definition transfers of these exquisite black & white classics are nothing short of lush. All six films are sourced from new, restored 4K digital transfers, with the exception of Morocco, which is sourced from a 2K source. The word “luminous” keeps coming up, but there’s a firm reason for that- these six films will radiate from your screen in a way they never have prior. It might just be the Blu-ray Box Set Of The Year.

That said, the lack of bonus features in regard to certain areas and films is weakest link in this endeavor. A little light on the whole in this department, Criterion has taken an interesting approach of veering away from providing extras specific to each film. Even the beautiful eighty-page booklet foregoes the usual film-by-film format, instead offering three broadly themed essays by Imogen Sara Smith, Gary Giddens, and Farran Smith Nehme.

With each film housed on a separate disc (in a cardboard case), Morocco gets the most bonuses, with a new short documentary about Dietrich’s German origins, another brief interview about the “real” Amy Jolly, whom Dietrich’s character is based upon and named after. There’s also a 1936 Lux Radio Theater adaptation of the film with Dietrich and Clark Gable. Dishonored contains another new short documentary, a satisfying one about the actress’s status as a feminist icon. This particular Dietrich doc is most eye-opening, as it sheds necessary light on much of the subtext and content of the films themselves.

Shanghai Express slows down further in quantity if not quality with its lone bonus feature being an excellent new interview with film scholar Homay King on Orientalism in the film. Blonde Venus’s handful of extras focus almost solely on the film’s fashion, and designer Travis Banton.

It’s with the last two discs where things really fall off bonuses-wise, as The Scarlet Empress has only an early 1970’s TV interview with Dietrich (a weirdly stiff and awkward one, at that), and The Devil is a Woman has just the audio of a song that was removed from the film. (“If It Isn’t Pain”, sung by a checked-out Dietrich). The shortchanging of these two films is particularly unfortunate. The Scarlet Empress is, in so many ways, the pinnacle of the pairing. Special attention could’ve been paid to the production design and the historical events it depicts. The Devil is a Woman could’ve offered special focus on the end of the road of this special era.

*****

While it may be true that von Sternberg’s head had contorted so far up his own backside that he could no longer fit into the emerging upright, broad-shouldered Hollywood studio mold, there’s no denying the impact of this work. Marlene Dietrich proved to be that singular, vital component in his vision as she emerged incomparable and immortal. Together, they are nothing short of history’s greatest director/actress pairing.

Thanks to this evergreen, must-have Blu-ray set, Marlene Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg can forever sing their legacy of light, shadow, art, image, and feminine mystery on our home media shelves.

The Devil Is a Woman

Director(s)

- Josef von Sternberg

Writer(s)

- Pierre Louÿs (novel)

- John Dos Passos (adaptation)

- Sam Winston (continuity)

- David Hertz (treatment contributor)

- Oran Schee (screenplay construction contributor)

Cast

- Marlene Dietrich

- Lionel Atwill

- Edward Everett Horton

- Alison Skipworth

The Scarlet Empress

Director(s)

- Josef von Sternberg

Writer(s)

- Catherine II (based on the diary of)

- Manuel Komroff (diary arranged by)

Cast

- Marlene Dietrich

- John Lodge

- Sam Jaffe

- Louise Dresser

Blonde Venus

Director(s)

- Josef von Sternberg

Writer(s)

- Jules Furthman (by)

- S.K. Lauren (by)

Cast

- Marlene Dietrich

- Herbert Marshall

- Cary Grant

- Dickie Moore

Shanghai Express

Director(s)

- Josef von Sternberg

Writer(s)

- Jules Furthman (screen play)

- Harry Hervey (based on the story by)

Cast

- Marlene Dietrich

- Clive Brook

- Anna May Wong

- Warner Oland

Dishonored

Director(s)

- Josef von Sternberg

Writer(s)

- Daniel Nathan Rubin (screenplay)

- Josef von Sternberg (screenplay)

- Josef von Sternberg (story "X-27")

Cast

- Marlene Dietrich

- Victor McLaglen

- Gustav von Seyffertitz

- Warner Oland

Morocco

Director(s)

- Josef von Sternberg

Writer(s)

- Jules Furthman (adapted by)

- Benno Vigny (from the play "Amy Jolly" by)

Cast

- Gary Cooper

- Marlene Dietrich

- Adolphe Menjou

- Ullrich Haupt