70s Rewind: THE MECHANIC, Terse Buddy Assassins

I pity anyone who saw Jason Statham's The Mechanic without having first seen Charles Bronson's The Mechanic. Because you didn't even get half the story. And the story's not even the point!

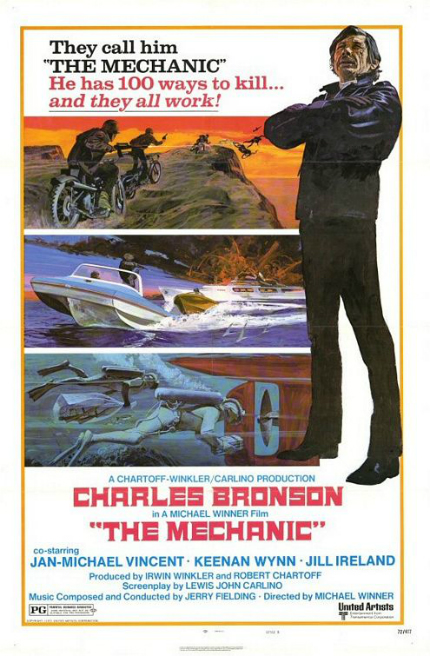

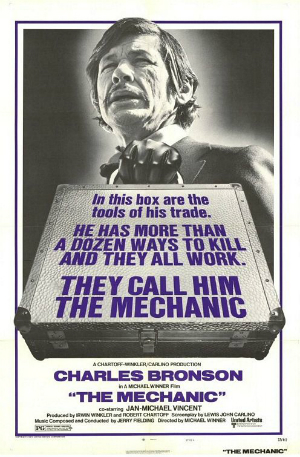

In my review of the 2011 version, I noted: "The 1972 original, written by Lewis John Carlino and directed by Michael Winner, set up Bishop, played by Charles Bronson, as an aging assassin, with Jan-Michael Vincent as the cocky young guy he takes under his wing. The action scenes were modest but precisely filmed; the characterizations provided understandable motivations without angst. It wasn't a deathless classic, but an efficient, well-crafted machine that got where it was going with a fair degree of style. The remake borrows the basic plot outline and characters, but in its rush to modernize things it ignores what made the original purr."

Having recently revisited the original film, I am even more convinced of its superiority, though I'm more conscious of its flaws now.

Free of dialogue and music, the first 16 minutes of the film fly by, eloquently establishing Arthur Bishop's character and modus operandi as he carries out an assignment. He is equally comfortable on the gritty streets of Los Angeles and in his well-appointed, yet not ostentatious, home in the hills. He drives a sports car, yet could blend in easily on public transportation.

We also learn that Bishop is not swayed by sentimentality in accepting assignments, or even his own fate. When he is diagnosed with a serious medical condition, he decides to start training a replacement for himself, a "cocky young guy" named Steve McKenna (Jan-Michael Vincent) who has taken an interest in him.

Bishop and McKenna bond over a disturbing, misogynistic evening, as they dispassionately observe the younger man's friend Louise (Linda Ridgeway) attempt to take her own life. Louise is already in a great deal of emotional pain, which makes it difficult to watch Bishop and McKenna take no more than a clinical interest in what she is doing to herself.

That's what convinces Bishop that McKenna is well-suited for work as a hit man, though their first job together does not go as well as one might expect, given all their preparation (as well as the examples of Bishop's previous work). It's an ill omen, but one that Bishop ignores.

As I've noted previously, British helmer Michael Winner began his directing career in the 1950s. He moved to Hollywood in 1970 and soon began a fruitful collaboration with Bronson, starting with the charged Western Chato's Land.

As I've noted previously, British helmer Michael Winner began his directing career in the 1950s. He moved to Hollywood in 1970 and soon began a fruitful collaboration with Bronson, starting with the charged Western Chato's Land.

The Mechanic followed in 1972 and it's a good example of what he brought to the table. He got along well with strong male stars like Bronson and Burt Lancaster, with whom he made the ruminative Western Lawman and the Euro-action spy flick Scorpio, which he made after The Mechanic.

He was a strong presence on set, according to cinematographer Richard Kline, and was apt to fire people who made what he considered to be serious mistakes. On the audio commentary that can be heard on a Blu-ray issued by Twilight Time (released in 2014 but, unfortunately, now out of print), Kline is quick to point out that he became a good friend with Winner while working together on the film, a friendship that lasted until the director's death in 2013. Kline, a two-time Academy Award nominee (Camelot, King Kong), provides many good, positive stories about Winner and Bronson, though he is less complementary about the European scenes that comprise a sizable chunk of the third act (and were shot by d.p. Robert Paynter).

And it's true: the scenes look just fine, but they are somewhat out of harmony, story and character-wise, from the rest of the film. Kline alludes to possibly another writer being involved. Reportedly, per Brad Stevens' book Monte Hellman: His Life and Films, Hellman was originally attached to direct and worked with Carlino on the script before producers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler switched studios and hired Winner.

According to Vito Russo's book The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, Carlino's script specified that the lead characters, Bishop and McKenna, were gay. Carlino said: "I wanted a commentary on the use of human relationships and sexual manipulation in the lives of two hired killers. It was supposed to be a chess game between the older assassin and his young apprentice. The younger man sees that he can use his sexuality to find the Achilles heel that he needs to win.

"There was a fascinating edge to it, though, because toward the end the younger man began to fall in love, and this fought with his desire to beat the master and take his place as number one. ... The picture was supposed to be a real investigation into this situation, and it turned into a pseudo James Bond film."

Well, that would explain things!

When I started my last revisiting cycle, I tweeted: "Umpeenth viewing; looks great on @twilighttimedvd Blu-ray. Concise script by Lewis John Carlino hints at something more, always. Charles Bronson and Jan-Michael Vincent are well-matched as terse buddy assassins." That sums up my feelings about the film: imperfect as it, it remains a personal favorite, from the first time I saw it on television in the mid-70s until today.

70s Rewind is a column that allows the writer to ruminate on his favorite film decade.