New Directors/New Films 2015: 10 Notable Selections From An Impressive Slate

ENTERTAINMENT (Rick Alverson) *CLOSING NIGHT

The name of the film is Entertainment, and yet, for long stretches of Rick Alverson’s fourth feature, it seems that what the filmmaker resolutely refuses to do is to entertain us, at least in the normal sense of the term. However, in its stead, Alverson leaves us with something much deeper, and much more disturbing and unsettling, than mere entertainment.

In fact, this film acerbically interrogates the very notion of what it means to entertain, and shows us what a performer goes through in exposing him or herself to the whims and the fickle tastes of an audience. The result is a vision and a cinematic worldview that is as uncompromising as it gets, and one that most definitely will not appeal to everyone.

Entertainment is built around the persona of Neil Hamburger, the nom de stage of lead actor Gregg Turkington, an anti-comedian character that Turkington has been performing as for two decades. If you’ve never seen him in action (as I hadn’t before watching this film), this will serve as your introduction. The act, which is performed several times in the film to increasingly violent results, is something that truly must be seen to be believed. Turkington/Hamburger gets into character by oiling his thin, stringy hair into messy, glistening clumps, which he spritzes with hair spray for good measure.

Dressed in a cheap suit, and precariously balancing three drinks and a microphone in his hands, he unleashes a torrent of querying non sequitirs that are deliberately off-putting and vulgar in the extreme. Here are a couple of examples of his bon mots: “What’s the difference between Courtney Love and the American flag? It would be wrong to piss on the American flag.” “What’s the worst thing about being gang-raped by Crosby, Stills, and Nash? No Young.”

The Comedian (as he’s called in the film) comes across in his stage act like a vaudevillian gone completely rancid, deliberately provoking his audience into hatred. And that he often gets, from the sparse crowds at the seedy dives where he performs. He returns their hatred with a string of invective aimed at the audience, especially those who heckle him. It’s an act that is so unfunny, it comes out on the other side to actually become hilarious.

The offstage person is a rather dramatic contrast to the Comedian’s stage persona; he’s a taciturn, withdrawn, seemingly depressed man, aimlessly wandering the California desert, desultorily joining and deviating from tourist groups. He encounters a number of others along the way, such as his cousin John (John C. Reilly), who voices support for his act, but gently suggests he tone it down to appeal to “all four quadrants” of a potential audience, maybe by not referring to semen so much. The Comedian frequently calls his estranged daughter, who never returns any of his messages.

As events become increasingly bizarre and surreal, the film suggests that Alverson could be this generation’s Samuel Beckett, giving us disturbing visions of an absurd, godless universe where any attempt at finding meaning or a purpose to it all proves to be a foolish pursuit. In the final shot, the Comedian finally laughs, but it’s a laugh divorced from any sense of happiness or mirth; instead, it’s an expression of complete resignation to the futility of his existence.

(March 29, 4pm and 7pm)

THE GREAT MAN (Sarah Leonor)

Intriguingly elliptical storytelling techniques, arresting visual compositions, and fine performances by both seasoned and nonprofessional actors elevate Leonor’s second feature above the overly earnest and sentimental pitfalls her narrative potentially lends itself to.

The nature of manhood and its connection to warfare, the plight of immigrants, the shifting and fluid nature of identity, father-son relationships, and camaraderie between men are just some of the subjects broached in this film. Divided into five chapters, The Great Man shifts from its initially child-like perspective of heroic soldiers facing down both other soldiers and wild animals to a more mature and clear-eyed look at the cruel, indifferent world that exists outside the cocoon of French Foreign Legion derring-do.

The assured craft of Leonor’s filmmaking glides subtly though its changing registers with nuanced precision and an emotionalism that its affecting without being cloying.

(March 28, 3:30pm)

CHRISTMAS, AGAIN (Charles Poekel)

The title of Poekel’s small-scale yet appealingly intimate debut feature aptly conveys the world-weariness of its protagonist Noel (Kentucker Audley), as he glumly works another Christmas season selling Christmas trees at a stand in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Despite his holiday-appropriate name, Noel is far from inclined to feel the festive spirit. He’s broken up with his girlfriend, who used to work the stand, and who everybody still seems to ask about. He often walks around in a surly funk, going through his interactions with customers, and often being frustrated with two new assistants who work the day shift, whose casual approach to their jobs and their status as a romantic couple equally irritates him.

Things promise to lift a bit with his chance encounter with Lydia (Hannah Gross), a young woman who he finds drunk and disoriented on a park bench, and who he brings into his trailer to sleep it off. The subsequent slow melting of Noel’s misanthropy and general depression due to this chance meeting is nicely underplayed, fitting in with the unforced, naturalistic, and mostly plotless nature of the rest of the film.

This brief (80 minute) feature may at first glance come across as rather slight, but this belies the attention to detail and the impressive visual craft on display here. Writer-director Poekel actually spent a few years running an actual Christmas tree stand (at the same location used in the film) with the express purpose of both researching his subject and raising the funds to make the film. This commitment pays off in its accuracy to the minutiae of the profession depicted in the film, as well as the warm, textured 16mm cinematography by ace cameraman Sean Price Williams. The result is a small, but subtly resonant and quite lovely film.

(March 28, 6:15pm)

GOODNIGHT MOMMY (Severin Fiala and Veronika Franz)

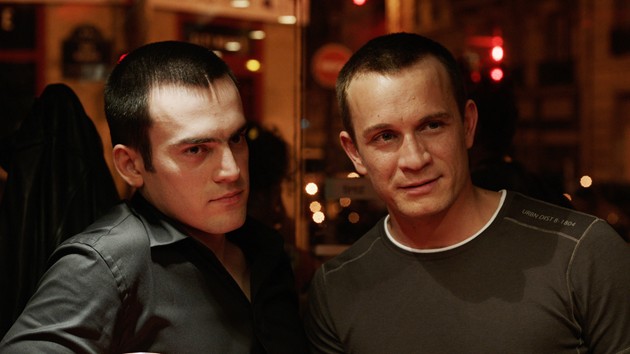

Twin brothers Lukas and Elias (Lukas and Elias Schwarz) don’t recognize the woman who calls herself “Mommy” in the nasty chiller Goodnight Mommy, a film the festival terms a “horror-thriller.” Despite this branding, while it does superficially take on the trappings of genre, it really is at its heart a disturbing psychological tale.

Fiala and Franz hail from Austria, which is largely why many commentators have compared this to the films of their countryman Michael Haneke. Again, Goodnight Mommy bears some superficial similarities in tone to Haneke, but a better comparison would be with another Austrian, Ulrich Seidl, with whom co-director Franz happens to be a partner and collaborator. The unnerving compositional tableaux and the wickedly deadpan sense of humor are qualities that this film shares with Seidl’s films, several of which Franz has co-written. (Seidl himself served as a producer here.)

When “Mommy” (Suzanne Wuest) emerges from the hospital and returns home after facial surgery, initially with her head wrapped in bandages, her chilly and stern demeanor toward her sons, as well as the way she ignores one of them, have the boys very suspicious. Soon they become convinced that this woman is not their actual mother, but an impostor; their feeling persists even after she loses the bandages.

This conviction leads them to become twin kidnappers and torturers, demanding that this woman admit who she really is and tell them what she has dome with their real mother. Fiala and Franz skillfully manipulate the ambiguous nature of their scenario, which makes us initially unsure of which side we should be on. There is a significant last-act plot twist, but one that is cleverly set up and discernible to those who have been paying close attention to the clues that have ever so subtly been dropped throughout.

(March 28, 6:45pm)

THE TRIBE (Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy)

Hands down, this film from the Ukraine was the most astonishing and audacious film that I saw in this year’s festival. Unfolding entirely without spoken dialog, The Tribe takes place in the environs of a school for the deaf, and the action is portrayed by actors who are actually deaf. There is no translation or subtitles provided; the actors communicate entirely through Ukrainian sign language.

However, the plot is so brutally and elementally simple that it is completely comprehensible without these concessions to audiences not versed in this language. (Obviously, those who can understand would be afforded another layer of meaning.) Forcing the viewer to interpret what is happening without these aids makes the title of the piece especially apt, with its anthropological connotations of an underground society that the viewer can observe only from the outside without being a part of it.

And what a brutal, dog-eat-dog society it is. Although this takes place at a school, very little education seems to occur, at least of the academic kind. Through the perspective of a new student who comes to the school, we witness his violent initiation into the gang that runs the school.

This gang’s activities include selling cheap trinkets on the trains and robbing the passengers of any unattended money or valuables, and – the activity that is most examined here – pimping out two of the female students to truck drivers at a nearby rest stop. The new student moves up the ranks to become the girls’ designated pimp; he makes the fatal mistake of falling in love with one of them, which brings about his ostracization, as well as the film's shocking denouement.

This is far from the earnest and uplifting kind of film we would expect with characters such as these. While The Tribe may initially come off as an elaborate stunt, the masterful technique on display trumps any misgivings along these lines. Slaboshpytskiy and his ace cinematographer Valentyn Vasyanovich provide masterful and mercilessly unblinking long takes which alternate impeccably composed static compositions and Steadicam motion which stalks the characters in an often painfully observant fashion.

The proceedings are peppered with some startlingly explicit sex scenes, as well as the far less titillating aftermath in one extended shot that is incredibly hard to watch. And if ultimately the main takeaway from all this is that those who are deaf and mute can be just as thuggish and ruthless as those who can hear and talk, this takes nothing away from this filmmaker’s sensational debut statement.

(March 28, 8:45pm)

THE DIARY OF A TEENAGE GIRL (Marielle Heller) *OPENING NIGHT

“I just had sex. Holy shit!” These are the first lines uttered by Minnie (Bel Powley), the protagonist of Marielle Heller’s period (1976 San Francisco) coming-of-age tale The Diary of a Teenage Girl, adapted from Phoebe Gloeckner’s 2002 novel. As told to her tape-recorded diary, Minnie has just lost her virginity, not to a boy her own age, but to a man 20 years her senior.

And this man, Monroe (Alexander Skarsgard), is, to make matters even more explosive, the boyfriend of her mother Charlotte (Kristen Wiig). These highly unusual circumstances are an extension of the free-love, hedonistic lifestyle of the late 70’s, especially in this family where the adults present are far more preoccupied with partying and doing coke than attending to their kids.

Indie movies, especially those coming out of Sundance, are rife with coming-of-age stories, and Diary of a Teenage Girl, at least superficially, hews to these thematic contours. This lends an air of predictability plot-wise; we know that it’s not a question of if, but when, Minnie’s diaries and the affair will be discovered.

But Heller introduces elements to counteract this familiarity, starting with the very startling performance by Bel Powley as Minnie. She’s in her early twenties, but convincingly passes for her character’s age. The intimate details of a young woman’s sexual awakening have rarely been made as viscerally and emotionally vivid as they have here.

This allows the scenario to avoid feeling like exploitation or mere provocation. It’s made clear that the affair is all kinds of wrong, but there is no simplistic judgment of who’s the predator and who’s the victim here. As played by Skarsgard, Monroe comes across more as a passive man who is unable or unwilling to take full responsibility for his actions than as a deliberate pederast. And the fact that Minnie at least partially initiates matters makes it a much murkier and more morally nuanced situation than it would at first appear.

Diary of a Teenage Girl also stands out for its visual style. Brandon Trost’s cinematography nicely captures the feel of the period; visually, the film resembles Polaroids that could have been taken during the period. There is also some animation that blends into the live scenery, representing Minnie’s artistic ambitions and the lively imagination and the joie de vivre that will allow this young woman to become a much more mature person than all the deeply flawed adults who surround her.

THE CREATION OF MEANING (Simone Rapisarda Casanova)

The title of Rapisarda Casanova’s second feature sounds abstract and theoretical; the film itself is anything but. Set in the bucolic climes of the Tuscan Alps, this film combines documentary and scripted scenes to beguiling, mesmerizing effect.

Starting with a historical discussion about the area – which was the site of a bloody battle near the end of World War II between retreating Germans and a coalition of Allied forces and Italian partisans – we settle in on a close observation of Pacifico (whose very name is suggestively symbolic), an aging farmer, as he goes about his rounds. The film alternates between following his solitary activities, listening in on his long conversations with others, and shots of the flora and fauna of the landscape.

This is a place where history is very much present, and not simply a distant echo of experience no longer heeded. The contemporary state of Italy and its myriad problems are presented as a predictable result of the errors of the past, which nevertheless are continually repeated. Rapisarda Casanova presents it all with impressive visual acuity and gentle humor, creating an experience as mystically ethereal as it is vividly earthy.

THE FOOL (Yuriy Bykov)

A plumber learns that you literally can’t fight city hall in The Fool, a tense and outraged indictment of the corruption, apathy and neglect that Bykov presents as depressingly endemic to contemporary Russian society.

Dima (Artem Bystrov), the idealistic Frank Capra-esque protagonist, is dubbed the titular appellation by others – especially his embittered mother – for not being ruthlessly ambitious or willing to take bribes, but instead studying for his civil service exams. The plot engine is set in motion when he’s summoned to a neighboring apartment building to take care of a burst pipe, which reveals a dangerous crack in the foundation that runs stories high.

He does some calculations at home, where he makes the alarming discovery that the building is hours away from collapsing on top of its residents. He crashes a fancy party being thrown for the mayor (Natalya Surkova), where Dima appeals to her to order an evacuation of the building. Little does he know that he’s about to uncover the true face of his local government, and the chilling lengths to which they’ll go to amass as much power and wealth as they can, and sweep whatever problems that arise under the rug.

The Fool is full of palpable class-based anger, but the sharp performances by the cast, as well as Bykov’s skill at maintaining a sense of racing-against-the-clock tension, prevent it from becoming overly preachy and strident. This film confirms its director’s status as one of the most promising talents coming out of Russia today.

THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (Nadav Lapid)

This strange and unsettling film out of Israel boasts a peculiar premise. Nira (Sarit Larry), the titular teacher discovers a precocious poetic genius among her charges: Yoav (Avi Shnaidman), a 5-year old who seems to have the preternatural ability to spontaneously compose poetry whose subject matter and diction are that of someone well beyond his years.

Nira becomes obsessed with both encouraging this boy’s talent, and protecting it from a society that she sees as hostile to any sort of artistic and poetic pursuits. Lapid’s second feature is a much more intimate affair than his politically minded 2011 feature Policeman, but one that is no less sharp in its observations of contemporary Israeli society.

And although by the conclusion Nira ultimately could be said to have gone mad, this film refuses to judge her harshly, and is much more condemning of her environment, which elevates banal practicality over the appreciation of true beauty.

WESTERN (Bill Ross and Turner Ross)

Eagle Pass, Texas and Piedras Negras, Mexico are neighboring border towns that, at least initially in Bill Ross and Turner Ross’ compelling and visually striking documentary Western, buck the stereotypical immigration-themed conflict between the two countries.

Both towns make a point of emphasizing peaceful co-existence and cultural exchange. Unfortunately, Mexican drug cartel violence upends this idyllic state, and the sibling documentarians skillfully examine the aftermath of what this does to both towns.

Alternating between the brutal occurrences of this drug war with more impressionist portraits of people conducting their daily lives amid the changing fortunes of their towns, Western upholds the storied tradition of cinema verite, while at the same time lending a unique and fresh perspective that is entirely theirs, continuing the gifts of observation evident in their first two features: 45365 (about their hometown of Sidney, Ohio) and Tchoupitoulas (about New Orleans).

More about Entertainment

More about Goodnight Mommy

More about The Tribe

Around the Internet

Recent Posts

Friday One Sheet: LIVING THE LAND

Now Playing: BLADES OF THE GUARDIANS and Some Other Movies

Leading Voices in Global Cinema

- Peter Martin, Dallas, Texas

- Managing Editor

- Andrew Mack, Toronto, Canada

- Editor, News

- Ard Vijn, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Editor, Europe

- Benjamin Umstead, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, U.S.

- J Hurtado, Dallas, Texas

- Editor, U.S.

- James Marsh, Hong Kong, China

- Editor, Asia

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana, New England

- Editor, U.S.

- Ryland Aldrich, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, Festivals

- Shelagh Rowan-Legg

- Editor, Canada