Acting Legend John Hurt And Co-Writer Kelly Masterson Talk SNOWPIERCER

Many moons past, at an NYC dinner where the soju flowed freely, Director Bong Joon-ho revealed his plans to adapt the French graphic novel, Le Transperceneige, as an international production. Five years later, Snowpiercer has finally barreled into US cinemas. I had the chance to speak with two of its passengers; Before the Devil Knows You're Dead scribe, Kelly Masterson, who co-wrote Snowpiercer's screenplay, and British acting legend (and a xenomorph's best pal), John Hurt. Both gentlemen sat with me to discuss the ambitious project, including the Weinstein cutting controversy.

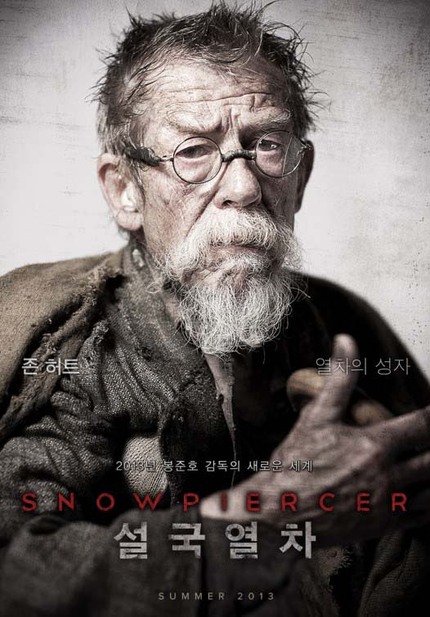

John Hurt

The Lady Miz Diva: What is it that brought you to this film?

John Hurt: Well, he's sitting over there {Points at Bong Joon-ho}. He's as cool as they come. I guess it was done through my agency; a meeting was set up in London and I went along and I met him and I met Doo-ho {Choi, co-producer}, obviously, because he's with him all the time like a devoted slave. I just fell in love with him. He was wonderful. I hadn't seen anything. I hadn't seen Mother or anything, which I immediately did when I got home. I went, "Wow, that's the chap I was talking to." Thank God instinct has left me completely. I adored him then, I adored him ever since.

Tilda {Swinton} and I don't want to work with anybody else, ever again, ever. There's a reason for that: He only shoots what he wants to see. That's unbelievable. We spend most of our lives doing the scene, doing the master, then doing it from that point of view, from that point of view and that point of view. And then they say, 'We need it nearer,' so we do it. They spend a lot of money for that, but... and you keep going, and you keep going, and it's called being professional. It's just being idiotic, really. But he'll stop me in the middle of the sentence, he'll say, "I don't need any more." Tilda and I, being a couple of old pros, say, "Wow! Early lunch!" {Laughs} It's extraordinary.

You've prepared everything, really, your mind's concentrated and clear and sober, and so you put it into the first shot and it's clear as a bell, and something might go wrong so you do it second time, right, or third, or fourth, or fifth. And then when you've done that, instead of saying, 'Now we'll do another scene,' we have to do the same fucking thing all over again. He says, "No, that's it, I don't need to." It makes a difference, believe you me.

With that different approach, did you feel more pressure to get it right in one?

JH: No, not at all, you just felt the enjoyment. It stopped being work. You just say, 'Right, I'll guess we'll do everything we can, let's do it.' And so we went through it with all the people who were involved, like Jamie Bell and Luca Pasqualino - lovely people, really wonderful - and you work away and get it as right as you can.

While you've worked with filmmakers like Fred Zinneman...

JH: Well, now, that's going back a bit.

...Sam Peckinpah, Steven Spielberg...

JH: I love him {Spielberg}, I think he's very, very nice, but I don't think he's clever as people like Zinneman.

You've also worked with directors just starting or very early in their feature careers like David Lynch and Ridley Scott...

JH: Yeah, well, Ridley, I'm the same generation as Ridley. I'm the same generation as Alan Parker. So we kind of grew up together, if you see what I mean. I did a film in 1973 of Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs; I wanted Alan Parker to do that, but they wouldn't let me. And I kept him in the back of my mind, and then when in 1977, Midnight Express came up and {producer} David Puttnam rang me up and said, Alan Parker wants you to do a film; I said, "Accept it." He said, "What? You haven't seen it yet." I said, "I don't give a shit. If it's Alan Parker, I want to do it." These are the marvelous things that are completely generational.

I'm often asked by people, 'What advice would you give to somebody of today how to behave in the business?' And I can't answer. I can't answer because what I would've done at a particular time like that, I couldn't possibly advise somebody else to do it. And anyway, it's different today; I mean, I went to the Antarctic and made a film in which five weeks of rushes were never seen - they piled up. There's no way.

Is there a creative spark that comes from working with directors at that very interesting point in their career, like Director Bong, who is making his most ambitious film to date?

JH: There's no question of him; he's got it. You might miss a few, but you'll get the right ones. I mean, I might work with somebody or see somebody who I missed as being somebody who is going to be terrific, but I knew it would be no problem. I mean, I'm lucky to work with him.

Your character, Gilliam ... By the way, I wondered if that was a tribute to Terry Gilliam...

JH: {Laughs} I know! Terry said, "Where did they get that name? Nobody's called Gilliam." I said, "Well it was given me, Terry," and I'm hoping to work with him next.

I'm excited for Don Quixote.

JH: Well, it hasn't been announced, really. It's not official. I've gotta to go back and do a test for the boy. I suspect he's testing me too, and you know, understandably. I know Terry very well and it's something I know that I could do and turn it into something really extraordinary.

Gilliam in this film has a very uneasy relationship that is unknown to Chris Evans' character, Curtis, who idolizes him. What do you think Gilliam truly believes?

JH: He believes completely in the status quo. He knows perfectly well. He started it with Wilford together. He knows what happens if you upset the status quo.

Yet Gilliam encourages Curtis to upset the status quo.

JH: He tells him, "I am a shadow of my former shadow." He tells him, 'Don't believe me.' 'Don't go with me.' He has to be aware.

Gilliam's playing God and his sacrifices and the reasons behind his potential deception set up some of the most interesting themes in this film.

JH: Well, they're provocative, that's the interesting thing. I mean, it's a comic, for God's sake. So therefore, you have to say it's a comic, but it's provocative. It says, 'Wait a minute, in such a situation, what would we do?' so on and so forth. It creates argument and that's a good thing. It's a bit like V for Vendetta. And you have this whole sort of ridiculous situation that you can put this music to, and it's wild and it works. But when somebody gets too close to the knuckle, you have to say, 'Well, wait a minute, baby, it's a comic.' This is not Midnight Express, this is not.

You are one the busiest 74-year-olds I've ever met, what is it that keeps you motivated to continue acting?

JH: As I've said before, I am the victim of other people's imagination. If they consider that I'm worth being in the film and they asked me, and I like it, I say yes. But if, when the day comes, they'll say, 'Oh, that silly old fucker's too old,' then I'll have to say that's the end of it, you know? I don't suppose I'll enjoy that.

Have you never wanted to direct a film?

JH: No, it's a different foundation. Well, it's a different talent - totally.

But you could write a book on acting.

JH: Oh, I could write a very bad book on acting.

Have you ever written an autobiography?

JH: I've been asked. But then, which one do you want to see or read? Because I will wake up in the morning, like you will wake up in the morning, and you will see yourself one way; you will wake up the next morning and see yourself totally the other way. Which one's true? So what do you write?

Is it harder to write about the real you?

JH: I don't know what the real me is.

I wonder if that's why you're such a good actor?

JH: I'm an amalgam, of course. I don't do anything clever. I just pretend to be other people.

Kelly Masterson

The Lady Miz Diva: Can you tell us how your collaboration with Director Bong began?

Kelly Masterson: He called me just out of the blue. He didn't know me from Adam; I didn't know him. He had seen a movie I'd written called Before the Devil Knows You're Dead, he called me, and said, "Would you collaborate with me on this project?" Not, 'Do you want to take a meeting?' 'Do you want to audition?' 'Do you want to interview?' It was just that simple. I knew Mother, so I said yes. I watched The Host and Memories of Murder, and I said, 'My God, yes, I have to do this.' But you know, I never talked to anybody else from that day until the day he screened it for me last summer. I never talked to anybody about it. No producers, no stars, no money men, no nothing, and it's such an un-Hollywood thing. I talked to one person, it was Director Bong; it was his vision, he wanted me and that was it.

How did it work logistically? Did you go to Korea? Did he come to you? Did you exchange emails?

KM: It was a little bit of email, we mostly Skyped. We met in LA once we knew we were going to do it and we talked about it for a couple of days; themes, characters, and then he sent me away to New Jersey and I wrote, and we'd get on the phone every Monday. I was in New Jersey at 7AM and he was in Seoul at 7PM, and he take a stab at a draft, send it back, and it was back and forth for about eight or twelve weeks. I can't remember exactly, but it was quick, it was fast.

It seems like in Korea, everything is done quickly; there's not a lot of time for rewrites. What was it like for you to work at that speed?

KM: It didn't ever feel fast. I don't think we rushed; I just think we knew what we were doing. It was his vision, he's a strong visual director; he knew what story he wanted to tell. He needed me to help, to flesh it out, to bring my talent to it. And you know, sometimes things are just meant to be and we wrote a really good script and it went pretty quick. What I loved about it was the freedom he gave me to explore, find new things and to develop the voices of these characters, and he is so creative himself, he brings such great ideas to the table, so it was a wonderful experience. That and not second thinking; once we knew we had the story, then he shot it. {Laughs}

Is this your first time adapting from a graphic novel?

KM: It is, yeah.

Did you read the novel beforehand?

KM: Certainly, yeah, I read it before I met Director Bong, and I met him, then I reread it as I was getting ready to start, and then I put it away. I put it away and I just let the story pull me through it, mostly Director Bong's version. Which isn't to say that there's anything wrong with the graphic novel - it's terrific, it was inspirational - but also we didn't rely very heavily on it. It was the premise and the inspiration and then we jumped off, or I guess I should say, we jumped on the train and let it pull us.

In the graphic novel, the action centers mostly around one character. As a writer, how did you accommodate this film's ensemble and how did you balance how much time you would spend on each character, because you come to care for them through the course of the film and each could easily have a back story of their own?

KM: I don't know that you know that as you're doing it. It sort of becomes apparent as you're doing it. We knew very early - Bong knew from day one that it was one person's journey; that it was Curtis' journey. It certainly involved everyone else, everyone brings something to Curtis because Curtis is the leader, and as Ed Harris's character says, "You're the only man who has walked the entire train." And so his journey is the entire train. All the other characters became important for how they gave information or help to Curtis and that's kind of how we figured out how important they were to the story and how much time you gave to each one of them; what their journey is going to be.

Thank you so much for saying we care about them, because as a dramatist, as filmmakers, we want to make sure that they feel real to you. The actors help a lot; you get somebody like Octavia Spencer, you don't have to do a whole lot of work because she's going to bring so much to it. But it's very important to me as a dramatist to make sure that all of them are human beings that they feel real, that they're not cardboard characters.

Prevalent in all of Director Bong's films is his sense of humor, which can be a little dark and twisted.

KM: Yeah!

There are things like the revelation behind the energy bars, Tilda Swinton's character and the scene in the school room that could have been over the top. Did you advise as to aspects that might have gone too far for the Western audience?

KM: {Laughs} You know, I love his dark, twisted sense of humor. It was one of the things that really drew me to working with him, so of course I would never hold him back. If he had an idea, let's absolutely try to make it work, because it can be jarring - especially for an American audience it can be quite jarring to have the darkness juxtaposed with the humor. There's a scene where a man's arm is being frozen, and then you see the look on Ewan Bremner's face, that sort of reaches this moment of serenity when he gives then surrenders to it, and then there's the sort of look of pleasure, of wonderment. That's Director Bong: darkness and wonderment and violence and humor all together, all sort of mashed up next to one another. I would never hold him back. I don't know that I ever really thought that anything was terribly inappropriate, so luckily I never had to. I love that first Tilda Swinton scene, it's so amazing.

Did you know that we didn't write that for her? That we wrote it for a man?

In the graphic novel, the character is male.

KM: It's a man, that's right. So she decided she wants to do it and I was so amazed. I was so surprised when I heard she was doing it and then I was so amazed by what she did with it; funny, scary, frightening - amazing.

And then suddenly there's a sort of musical sequence in this brightly colored schoolroom full of baby fascists. Has anything this bizarre or surreal crossed your path as a screenwriter before?

KM: Not really, because this is the most unusual thing I've ever written. I got lucky enough to get hired to adapt a Kurt Vonnegut short story at one point, and it had a sort of similar tone to it. The humor - because Kurt Vonnegut was of that similar sort of mind of very serious things also mixed with a lot of humor - this was a wonderful opportunity for me to get a chance to write that. I loved writing that scene, I got to write those lyrics.

What was your feeling when you heard that SNOWPIERCER stood to lose about 20 minutes in its US release?

KM: Oh, I was upset. I had already seen Director Bong's cut, so I knew how brilliant it was and how I didn't want to lose a second of it, but then as a writer, of course that's the way I always feel, 'Don't touch my words,' but I didn't want anyone to touch his vision and I wanted people to see it. It's going to be hard for some American audiences because it's an unusual film, it's different, it's unique, but that's what's so wonderful about it. So, I was upset when I heard that was gonna happen. Director Bong called me, he showed me the film and asked me if I would help him write some voiceovers so in the event any of it was lost, we would make sure that the story still was clear; the characters and their journeys still were clear. So we wrote those and luckily we never had to use them - thank you Harvey {Weinstein} for being generous enough to let Director Bong's vision - his cut - be seen.

Director Bong has written all his films and I think people will be curious as to what exactly your role in the script was? Could you please tell us in your own words?

KM: Well, the most important thing I did was to bring Director Bong's vision to life, because when we sat down in LA, he knew the movie he wanted to write, but he didn't know how to get there, because 90% of the movie was going to be in English and he certainly needed me for that; but I think the reason he chose me was he needed those characters to be interesting and complex, fucked up and desperate, and he knew I could do that - that's kind of what I do. So when you see the movie, you will see an amazing visual experience and you will know that that came out of the mind of Director Bong, but when you hear the words, when you take this journey with these characters, you will know that a lot of me is in that, so you'll see that.

What has the experience of collaborating with Director Bong brought to you and your work going forward?

KM: I've never gotten to write anything of genre. I've never done a science fiction movie. Who would ever hire me to do a science fiction movie because of the kind of work I've done? So, it's opened all these new doors I never had before. I think I've been offered three adaptations of comic books within the past two weeks. Career change what it does and it gives you so many more opportunities. It opens up not just your opportunities, it opens up your mind to what you're capable of doing. Four years ago, I would never have dreamed that I would be writing this kind of the movie.

The science fiction genre allows for almost limitless imagination, doesn't it?

KM: And you know, it's a wonderful exercise for me because I oftentimes really try to ground everything in reality; which is the important thing to do for the characters - all the characters need to feel real - but to open up that imagination and think of new things. If you're on this train, what does God mean, and in this case, it means the engine, it doesn't mean some other story it means, what is keeping us alive, what is the most important thing, what do we worship? If you're on the train, how do you get high? See, that's the kind of thing that begins to lead you to invention which I would never have known unless I was given the opportunity.

Director Bong's work often features the premise of the small guy against impossible overwhelming odds. Does that theme ever get old?

KM: No, it doesn't. David and Goliath. We love the underdog. We love the little guy. And the thing that's interesting to me about this, and I didn't know that I was thinking about it when I was writing it - I know it when I watch it, is that it's not just the little guy against the big guy, which certainly is part of the story and certainly part of all of our stories, we all feel that way - but this is a little guy against the machine - literally, against the machine. So it's in a way a very modern take on that David and Goliath story. It's a very modern story of man against machine.

Since we're getting biblical, there's a little Adam and Eve thrown in.

KM: Yes, there is, and throw in a little Noah's Ark on the way, too. Because Director Bong would always talk about "this rattling ark." It's what you would call the train, but it's a little bit of people from England, people from the United States, people from Africa, people from Europe, people from Asia, all aboard one train.

This film ends on a sort of open page and there is a second SNOWPIERCER graphic novel. Has there been any discussion of a sequel to continue either where the film leaves off, or perhaps to adapt the second book?

KM: I haven't heard any talk. I haven't heard anything. If Director Bong wanted to do it, I would love to. I would love to jump at it. I would love to know what happens, too. So start a rumor! {Laughs} Write 'Sony and Universal are fighting for the rights to the SNOWPIERCER sequel,' please. {Laughs}

What would you like audiences to take away from SNOWPIERCER?

KM: Hope - which seems very unlikely - and I'm so glad you asked me, because it's a dark, bleak, violent story, but I think ultimately very hopeful. The reason we are doing this is to define ourselves, to reinvent humanity, to give humanity a chance to go on and to be successful. And I think when you reach the end of this movie, hopefully the message you will get is there is hope for all of us.

This interview is cross-posted on my own site, The Diva Review. Please enjoy additional content, including my exclusive interview with Director Bong Joon-ho and photos from the NY promotions there.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.