Review: NIGHT MOVES, A Tense Showcase Of Guilt And Paranoia

When purchasing a used boat for an act of extreme vandalism, a young activist quips that she chose the one named "Night Moves" because it was better in her mind than "Sea Breeze" or "Heart's Ease."

I tend to pay attention to the names of boats and films because they are usually chosen with care. This is doubly-true when the name of the boat also happens to be the name of the film. And I'll admit, part of me wants Kelly Reichardt's choice of names to be based on the Gene Hackman noir from 1975 (directed by Arthur Penn), which does indeed feature a sinking boat, along with a healthy dose of paranoia and confusion and stylish ineffectuality. It's certainly a better boat name than The Conversation.

But I digress.

Reichardt has become a marquee name on the festival circuit with her last three films, Old Joy, Wendy & Lucy and Meek's Cutoff. All three are decidedly different animals story-wise, but all deal with being lost on some level, and are told with an in-camera intimacy that has made her one of the more interesting American auteur filmmakers.

Dena (Dakota Fanning) and Josh (Jesse Eisenberg) both work jobs outside the mainstream. She helps maintain a 'wellness spa' where old ladies dip in hot pools while soothing music is piped in. He works on a co-operative farm that puts local organic vegetables into the hands of local Oregon folks who are probably proponents of the local food movement. They both eschew the feel-good brand of activism found in earnest documentaries, such as the one a cute girl shows at a local meeting. (The credits reveal that the film within the film was shot by Reichardt's onetime producer Larry Fessenden, which I find cheeky considering his own eco-horror films.)

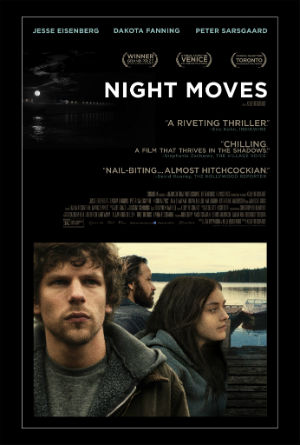

Anyway, Dena and Josh have bigger, far more hands-on plans of direct activism. They buy the eponymous boat and hook up with the rather shifty Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard, at his most Sarsgaard-ian), who can turn 500 pounds of fertilizer into a bomb, for which the "Night Moves" is the delivery vessel.

Dena is the smooth operator, handling the fertilizer buy with quick-on-her-feet confidence. Josh is more jittery, but clearly focused on details. Harmon has the resolve to do what needs to be done, and not sweat the small stuff. They make an effective team for an eco-mission that, like any kind of illegal job, has its share of problems to be solved in-situ, along with anxieties about problems that may or may not come up.

For example: Is a car driving by a curious cop? Will a camper or a hiker notice the intensity of their conversation, or the yellow bags of explosives piled high in their pleasure boat? Reichardt has this nervousness permeate not just the job, which plays out somewhere between the Hitchcock-bomb-not-going-off ethos and the political frisson of Clouzot's The Wages of Fear, but more mundane, subtle situations, such as Josh's casual delivery of food to their RV back in the woods, where, outside the vehicle, he hears giggles and breathing that may mean sex.

Josh is so solitary onscreen that we might wonder if he understands how wrong (or how ineffectual) their act of terrorism will be. Earlier, we see him picking up a fallen bird nest and attempting to put it back in a tree. Most people would know that no birds will come to this previously tarnished nest off the ground, just as blowing up a dam may not help the already compromised salmon spawning run on the Oregon river system that has been repurposed for cottages, camping and electricity generation. The after-effects of their job are even more complex. Will they be recognized? Will anyone have guilty urges to tattletale?

Josh is so solitary onscreen that we might wonder if he understands how wrong (or how ineffectual) their act of terrorism will be. Earlier, we see him picking up a fallen bird nest and attempting to put it back in a tree. Most people would know that no birds will come to this previously tarnished nest off the ground, just as blowing up a dam may not help the already compromised salmon spawning run on the Oregon river system that has been repurposed for cottages, camping and electricity generation. The after-effects of their job are even more complex. Will they be recognized? Will anyone have guilty urges to tattletale?

The filmmaking certainly foregrounds the effect of doing something you know is wrong, regardless of how noble the reasons are. Every little noise or interaction becomes pregnant with a meaning that relates back to the characters' own guilt. The idea of the fallout is equally detail-driven, and much harder to deal with, than the action of committing the crime.

There is beautiful sound design and cinematography here serving to heighten the kind of paranoia that picks at Josh, and causes an ugly rash to break out in Dena. We hear Harmon's breathy-calm voice over the phone, and even though he's a bit greasier than the other two, we know he is not immune, either. The idea of modern society as an unbreakable grid where everything is connected is brought up at one point, but is that more of a discomforting construct, an excuse, rather than a profound reality?

I especially adored the line of dialogue, "All roads in Oregon are long." There are no shortcuts in this type of movie making. Such is certainly the case in Reichardt's previous works, which are all meticulous road movies of a sort. This one shares that sensibility, and the destination is more unsettling, rather than elucidating.

Night Moves may have a plot along the lines of a more conventional Hollywood thriller, but it's Reichardt's brand of filmmaking to the core. As many have rightly observed, this tense, quiet thriller is a good initiation into her brand of filmmaking. Arthur Penn would be proud.

Review originally published during the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2013. The film opens in limited release in the U.S. on Friday, May 30, before expanding across the country in the following weeks.