Review: THE VIGIL, The Longest, Darkest Night of the Traumatized Soul

I doubt there is any religious belief system on the planet that doesn't have some kind of, if not exactly evil, menacing force as part of its folklore. And it always irked me that Christianity had such a monopoly on horror films (seriously, why do vampires only respond to a cross?) (*And yes, I know the answer, it's a rhetorical question to prove a point). There are so many configurations and manifestations of our fears in the form of monsters, demons, ghosts, that speak not only to us as humans, but to the religions and cultures they come from, and a wealth of stories to tell that will frighten us to our core.

The Vigil, Keith Thomas' feature debut, is set within a very small, unique, and relatively closed cultural landscape, one which outsiders barely get glimpses of, especially of the more intimate and personal kind. Set during the course of a single night, when one man, in need of money, agrees to perform a task that will unleash the darkest horror on him. It's the kind of claustraphobic terror that should leave the audience shaking and unable to look away.

Yakov (Dave Davis) has recently left his tight-knit Orthodox Jewish community (for reasons that will be revealed); he attends a support group of fellow 'refugees', who band together to try and navigate the secular world. But money is tight, to say the least, so he agrees to take on the job of Shomer for the night. The Shomer must stay up for the night, watching and praying over a recently deceased community member, until the body can be removed. Yakov arrives to find the deceased man's wife acting strangely, and as the hours pass, Yakov knows it's not just the two of them in the house.

Right from the opening, Thomas puts us into the claustrophic, no-way-out state: the support group, helpful as it is, is an atmosphere of shelter that hides a deeper pain, and even the short journey from there to the house of the deceased, through the streets of Borough Park, feels like Dante being lead to his journey through the Inferno. Every moment to when he enters the house, is indeed still part of theat pressure, that dark space that Yakov has lived since the traumatic events that irrevocable altered his life; what he finds in the house amplifies it to terrifying proportion.

Thomas understands the weight and thickness of long-held trauma; how an event such as the Holocaust, both a personal tragedy and a genocidal act upon millions, creates a wound that cannot properly heal. The body Yakov is watching, Mr. Litvak, seems to be haunted/possessed by a dybbuk, a demon that feeds on that trauma. This naturally leads to a lot of jump scares; but in the same way as recent horror films Get Out and Under the Shadow, these scares are neither cheap nor shallow. The traumas are ones that the world will not let people like Mr. Litvik or Yakov heal as they should; precisely because of their status as Jewish people, they are forced to wear it and endure it wherever they go.

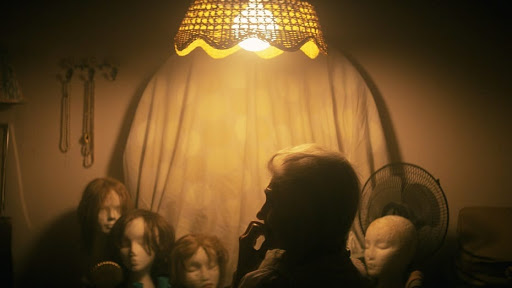

With the work of set design, sound design, and cinematography combining to create a house of horrors, the Litvak residence at once feels like your Bubbie and Zadye's house - crammed with mismatched furniture and knicnknacks - and one of the saddest terror, with a demon that is lurking in every shadow. Mrs. Litvak (the great Lynn Cohen) doesn't lurk so much as waits until she knows Yakov needs a warning or explanation. Somehow she is immune from the demon, it not finding her a tasty enough treat. She knows that Yakov is more than vulnerable, he's about to gain a horrible lifelong companion that will slowly drain his soul, and she can do little but guide him.

There are horrors in the basement, memories of the Holocaust and what happened to Mr Litvik; as Yakov explores, his own trauma is revealed. Like anyone after a horrible event, Yakov asks, why him, and as someone whose existence once revolved around his faith, he is in despair as he feels abandoned by his god. So who else to fill that empty, lonely place, but the dybbuk? Thomas infuses every inflection, every flicker of Yakov's face and voice with the pain he carries, as someone who cannot find the strength or the skills to exist in the world, one which mocks his faith, a faith he is not even sure he can claim anymore.

But is his faith his only chance at survival? As Yakov walks the seeminly endless halls of this house, no longer a home except for pain, in a final bid to confront and expel the demon, he puts on the Tefillin, as both armour and weapon. For this moment, his faith is not a burden nor a source of pain, but that of strength, as heavy as it metaphorically might be.

The Vigil does not hold back in its intensity and its anger at what one man, and the marginalized group to which he belongs, must endure, and the demons that constant follow in their trauma's wake. To see this told from a unique perspective with this particular cutlural/religious metaphor is one of the great advantages of horror stories, and I hope for more stories from this perspective, to continue to shake up the genre.