Review: WE ARE THE FLESH, Lucifer Rising

The budding filmmaker Emiliano Rocha Minter, a 26-year old from Mexico, emerged with his feature debut at International Film Festival Rotterdam earlier this year, finished only a couple of days before landing in Netherlands.

It wasn't his first visit to Rotterdam, though. Minter introduced his short film on the turf that prides itself on helping and promoting young talents with vision and style. Three years ago, the director presented Dento in Rotterdam´s dark rooms, a macabresque apotheosis of one's right for "exitus". The prospects of a feature-length endeavour from the filmmaker enticed curiosity even without endorsements from Carlos Reygadas and Alejandro González Innáritu; however, that never hurts.

The initial shot of Minter's first feature-length film We Are the Flesh (Tenemos la Carne) opens in the dark, derelict interior of a seemingly vast warehouse, where an unnamed character proceeds to engage in a ritual of low-fi alchemy, conjuring up a vial of miracle juice whose ingredients its foul taste and smell. Rotten eggs come into the mix at some point. The man's solitude is soon disrupted by an unexpected visit.

A pair of siblings came crashing into the lost kingdom of the shabby industrial complex, a messy ivory tower of sorts. Possibly orphans, having nowhere to go and nothing to eat, the man who goes by the name Marianno lets the siblings into his company under several conditions. The encounter eventually leads to a master and apprentice scenario, although very soon the thick crust of paranoia has been cut through by transgressive acts.

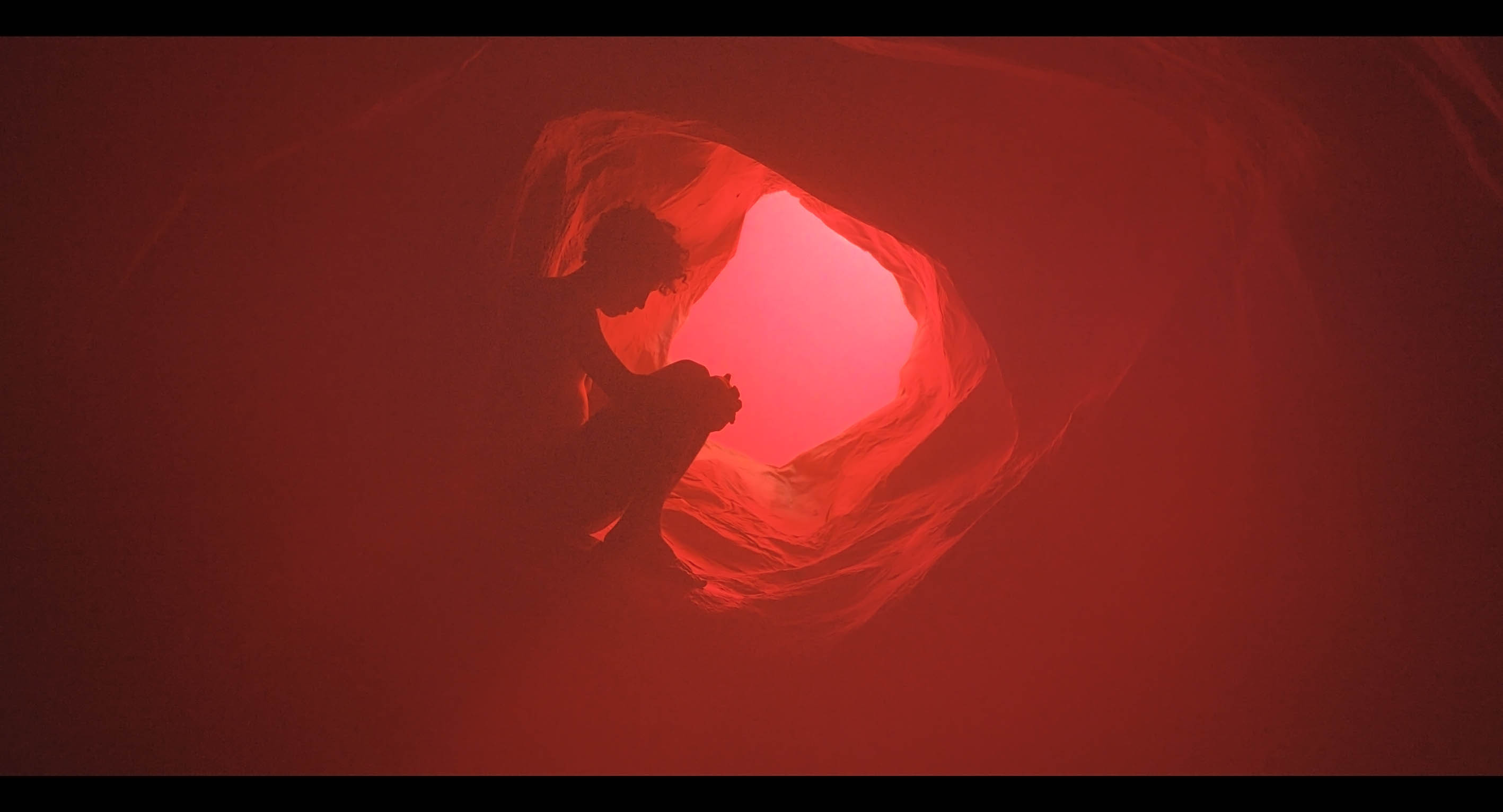

The girl, a carnal type harbouring an uninhibited spirit, strikes a chord with Mariano right off the bat, regardless of the fact that he resembles a Mexican incarnation of Charlie Manson. He's a patriarchal authority: a dictator, a father figure and a preacher. As payment for enjoying the low-life bed and breakfast, the siblings have to help Mariano build a cavernous structure, resembling and functioning as nothing other than a cozy, protective womb.

The brother and sister dynamic thickens, as the over-protective brother does not have much trust in the enigmatic Mariano, a delusional charmer with a demented smile and a Luciferian aura whose means of pedagogy brushes shoulders with a rather sadistic series of threats. Minter opens on a revisionist note of Hansel and Gretel: the siblings find a holy madman, a libertinistic philosopher instead of an old cannibalistic witch. Marianno has no interest in devouring their young flesh, as he has a big appetite to mold their flesh for the purposes of secret corporeal lusts and life at the same time. After all, they are now family.

The camera keeps wandering in the maze and the womb, never establishing a connection with the outer world, except for the revelatory closing shot. Rummaging in claustrophobic spaces with washed off walls and mess lying all around, the siblings find themselves in a temple of new flesh, Mariano heading the ceremony. Portrayed with exceptional gusto by Noé Hernández, an experienced Mexican actor, Mariano hits the fine line between insanity, enlightenment, and ambiguity, embraced by his rebirth from a dirty Mephistopheles into a sleek Messiah, the transition triggered by an ejaculation scene worthy of French provocateur Gaspar Noé.

The director, consciously or unconsciously, ranks among current filmmakers stylistically devouring the aesthetics of porn, which has mostly been associated with the French New Wave, though other directors have also revived it recently. In addition to Noé´s Love (read Jason Gorber's review), Eva Husson brought a stab on porn and pop in the sexually open Bang Gang (read Kurt Halfyard's review). Minter shoots the situations and acts with a relentless fervour for biological details, being visually and stylistically closer to Noé's poetics rather than Husson's

The internalization of the plot, imprisoned in between the four walls of the warehouse and then the cave -- a micro-universe within a micro-universe -- serves as a portal from a society of outcasts into a collective mind. As the plot progresses, the man-made cave snowballs into more connotations, a womb as a shelter alongside a cocoon, since not only the leading protagonist/priest morphs into a new being but, less literally, the sibling couple, or the male part of it, learns to embrace the repressed.

The first half, devoted to sanctuary-seeking and maintaining the odd asylum, can be easily understood as a parable on the contemporary Mexican social situation, especially through Amat Escalante visceral and gripping depiction captured in Heli (read Eric Ortiz Garcia's review). The mood of the second half swings from paranoia, insecurity, fear and menace into euphoric, unburdened and freedom-embracing delightful. It takes place in a slightly psychedelic and temperamental atmosphere, marked by a climactic and tad surreal explosion of colors.

Surprisingly enough, the younger generation of artists tend to thematize the negative pole of life in emo-autopsy of whatever traumas, small or big, they encountered. Minter goes boldly against the trend, launching an orgiastic fiesta modus, glorifying freedom in jolting-down the shackles of restraint and the unpedagogical, parental, warning of you-should-not in a bid for self-reinvention.

We Are the Flesh is a balls-to-the-wall crash course in latter day enlightenment, heavily inspired by French guru and mentor Donatien Alphonse Francois de Sade and the philosophy of libertinism, packing several other stabs at undermining the austere and traditional Christian logic of approaching life and its circumstances. Excessive, corporeal and transgressive is Minter´s debuting opus, a celebration of boundary crossings and defeating of mental obstacles, an effort the director himself manifests in a (vagina-)in-yer-face style.

The film is a pean to liberty designed as a fairy-tale for adults, acknowledging the archetypical foundations, either of fable or Christian myths, and dominated by corporeality in consuming and copulating, the basic definitions of human traits. Despite being based in the lower stratum of the pyramid of needs, similarly to de Sade, Minter gets his message and statement, accompanied by a social commentary on ossified communal consciousness rigorously adhering to inbred conventions, preventing a progressive development, and eventually the big mystical entity we call happiness.

We Are the Flesh

Director(s)

- Emiliano Rocha Minter

Writer(s)

- Emiliano Rocha Minter

Cast

- Noé Hernández

- María Evoli

- Diego Gamaliel

- Gabino Rodríguez