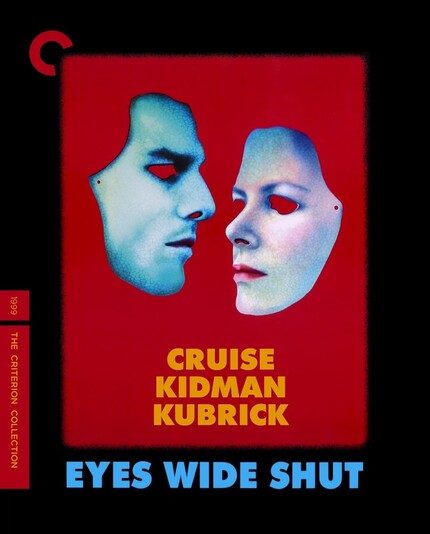

EYES WIDE SHUT 4K Review: Kubrick's Last Masterpiece

Just in time for the holidays, the ultimate Christmas movie (eat it, 'Die Hard'!) drops into the Criterion Collection

I was a late adopter on Kubrick. Very late: it took me until the director's last film to get as weird and obsessive about the filmmaker's vision as other people do re: Barry Lyndon, A Clockwork Orange or 2001.

But Eyes Wide Shut, to me, is a perfect film, and has become a kind of skeleton key for the nature of cinema itself: an utterly beguiling metatextual labyrinth that wanders through a dream space more effectively than nearly any other treatment of the subject.

Kubrick's adaptation of Arthur Schnitzel's Traumnovelle (literally, "dream novel") foregoes berserk surrealist imagery or overtly cinematic effects for the elusive way that narrative, itself, unfolds in dreams: a string of non sequitur developments that feel uneasily natural, shot through with subsurface urges that are tantalizingly, frustratingly inexpressible.

All to say: it's a film about desperately needing to get laid, and getting endlessly, effortlessly sidelined.

Before he made his living daring Xenu to kill him on camera in increasingly improbable Mission: Impossible stunts, Tom Cruise spent a good portion of the '90s working to convince Hollywood and audiences alike that he was a Serious Actor, Actually. The two efforts as such for which he will likely always be remembered came out within six months of one another in 1999: Paul Thomas Anderson's Magnolia, in which Cruise excels as a protean Men's Rights Activist; and Kubrick's secrecy-shrouded final film, in which he plays the opposite: a man so sexually bewildered that the Fates themselves seem to be conspiring against his ability to get his rocks, in any meaningful way, "off."

The plot outline of Eyes Wide Shut couldn't be simpler. Cruise plays Bill Harford, a young and wealthy doctor in an upper-upper-class New York that likely never existed (or at least, did not exist in the 1990s). His wife is Alice, played by Nicole Kidman; Kidman and Cruise were married at the time, which substantially upped the voyeuristic titillation of the project.

After a boozy, flirty Christmas party, Bill and Alice get into a fight about fidelity, and Bill, bless him, is astonished to learn that women have sexual interests, too (!). He heads out into the night on a house call and ends up lost in a disjointed labyrinth of encounters, as he tries to formulate some kind of sexual revenge on his wife for her unfaithful thoughts.

At the centre of the maze, he bamboozles his way into a private orgy to which he has not been invited, the image sequence for which the film is most remembered. Bill spends the rest of the film trying to work out the truth about the off-limits, paganistic sex club; while being warned -- and eventually threatened -- away by the shadowy figures behind it.

What's fascinating about the treatment in Eyes Wide Shut (well, one of the things) is that Alice's "adultery," which has Bill so steamed up, is merely an account of a passing fantasy; and yet after Bill leaves the apartment for the house call, he fully seems to fall into a dream, himself.

The languid stretch of frustrating failures and bizarre encounters (Rade Sherbadjia's midnight costumer, quietly pimping his adolescent daughter in the back room of his shop, remains memorable) seems to go on forever, while obeying no real-world mechanical logic. (How much can one really get done between last call at a jazz club and the afterparty start time of a Roman orgy in the suburbs?)

Even the environment seems to be a hall of mirrors: Kubrick shot his fantasy New York on the backlot at Pinewood Studios in the UK, leaving Bill wandering the same block and half for night after night after night. I've always been struck, too, by the fact that in each new place Bill visits, what seems like the same Christmas tree stands in a corner: they vary in size and weight, but always have exactly the same composition of colour lights.

In the back half of the film, after the invite-only sex party, everything Bill has encountered in the first half seems to double back on itself, both in reverse and at one step of remove. People he's looking for have vanished or turn out to be dead; doppelgangers fill their spaces instead (a sex worker from the first half is "replaced" by her roommate; both are equally attracted to Bill, but he can't make heads or tails of a pass at either).

Peering through the bedroom window at Bill and Alice's marital instability, which can't help but evoke the real-life "Tom and Nicole" coupledom, is uncannily frustrating as well. Eyes Wide Shut, by positioning Cruise as the ultimate cuck, plays the megastar so far against his established type at the time that it proved ungraspable for contemporary audiences.

Bill flashing his medical license like he's Fox Mulder squinting out from behind an FBI badge is scream-inducingly funny, as is his po-faced bewilderment when a hotel manager (Alan Cumming, a perfect one-scene stealer) nearly drools all over him with unbridled gay lust. A lot of the film is funny, but it's the uncomfortable sort of funny of a random stranger letting off a squeaker in a crowded elevator.

Kidman, meanwhile, gives the most extraordinary performance in the picture, a boiling storm of emotional chaos scarcely contained within a placid, "good wife" smile. She opens the film slipping off her clothes -- and Kidman is a spectacular nude, in a film chock-a-block with them -- and then goes on to give the weirdest, uncanniest performances of both "drunk, lusty" and "high, aggressive" that have ever been done.

The script asks a lot of her -- there are long, anguished speeches recounting dreams of adulterous orgies; and her wretched, thousand-yard stare in the famous final scene is incredible -- but Kidman finds her notes every time.

Kubrick was notorious for his dozens of takes, which only makes the actor's performance more impressive; the idea of having to sustain some of these sequences over what might have been weeks of shooting is an emotional workout just to think about.

Sydney Pollack, also a director and appearing here in an anchor role as one of Bill's clients, has an extensive interview in the Criterion disc jacket about Kubrick's meticulous approach, and his own resistance to it. An essay by crime author Megan Abott appears in the jacket as well, tracing Eyes Wide Shut back to both Traumnovelle and Kubrick's personal interest in the project, which stretched back decades.

Newly restored from the 35mm camera negative in 4K with Dolby Vision high dynamic range applied, the film looks great. Grain is showy at times -- but this is by design, as Kubrick, who preferred bright, glowing images, pushed the film stock two stops in processing in collaboration with his lighting cameraman, Larry Smith, who describes the approach in a newly-recorded interview on the disc.

Smith has gone on to re-time the entire picture during the restoration, attempting to bring it as close as possible to what he believed Kubrick was looking for, as Kubrick died before the film was originally timed.

The resulting image has extraordinary depth and colour fidelity, even given that the colours (nighttime blues; tungsten oranges) are intentionally oversaturated. This is the best I've ever seen the film look, including 35mm print projection.

(Of note: it's the international cut of the film, i.e. the one without the digitally-composited doubles obscuring the orgy scenes that were required to achieve an R rating in the United States. The weirdo completist in me would have appreciated having the North American cut as a branching option -- for one thing, especially for its era, it's one of the most seamless visual effects I've ever seen.)

Supplements on the Criterion edition, spine #1290, are extensive, ranging from featurette to feature-length.

In addition to the Smith interview, there are new interviews with set decorator / second unit director (an unusual combination! And she's a great interview) Lisa Leone, along with archivist Georgina Orgill.

From the archives, we get a legacy interview with Christiane Kubrick, the director's wife; Kubrick himself, accepting a DGA award in 1998; and a press conference from 1999, featuring Cruise and Kidman.

"Lost Kubrick" details the aborted development of Kubrick's Napoleon biopic, and his film about the holocaust, Aryan Papers. There's also "Never Just a Dream" from 2019, briefly recounting the production of the film and Kubrick's death.

Finally, "Stanley Kubrick Remembered" is from 2014, an 83-minute memorial of the director himself, and includes interviews with Eyes Wide Shut alum -- and eventual Tàr director -- Todd Field, along with scene-stealer Leelee Sobieski and longtime Kubrick chum Steven Spielberg.

On the latter note, and speaking of Kubrick's late-career work: let's get a 4K release of A.I.: Artificial Intelligence happening, yes?

Note: the trailer below is definitely NOT from the 4K Criterion edition; it's just added to remind.

Eyes Wide Shut

Director(s)

- Stanley Kubrick

Writer(s)

- Stanley Kubrick

- Frederic Raphael

- Arthur Schnitzler

Cast

- Tom Cruise

- Nicole Kidman

- Madison Eginton