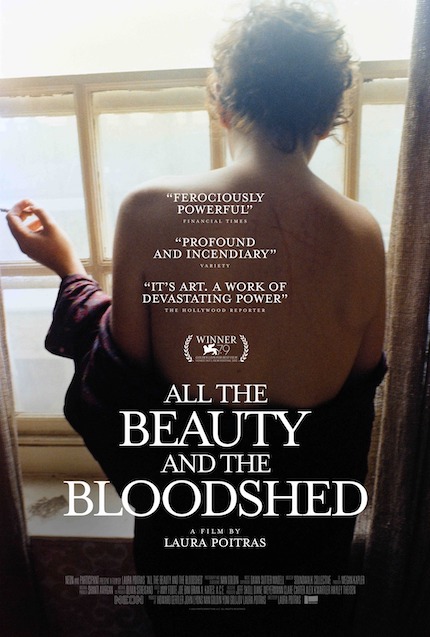

Review: ALL THE BEAUTY AND THE BLOODSHED, Epic Portrait of An Artist

Director Laura Poitras illuminates the artistry and activism of photographer Nan Goldin in her Golden Lion-winning awards contender.

There are many interesting films to be made about American photographer and activist Nancy “Nan” Goldin, now 69 years old.

You could make a film about her interesting and colorful personal life or about her impact on the 80s queer Manhattan sub-culture that she was a starring member of.

You could also do a retrospective of her subversive photography and its influence on modern contemporary pop art. Alternatively, you could make a film about her battle with Perdue Pharma (and its owners, the wealthy and powerful Sackler family) to bring justice to the victims of the devastating opioid epidemic sweeping across America. Director Laura Poitras, in a remarkable feat, has made all of these films at once in All The Beauty and The Bloodshed.

To accommodate its vast focus, the film is structured along two parallel tracks that are skillfully interwoven. The first of these (the “Beauty” track in a way) is the story of Goldin the person and the artist, tracking her life in chronological fashion from her unhappy childhood in the early 60s to the maturation of her artistic mission in the early 90s. The second (the “Bloodshed” track) traces her activism work from 2018 to present day as she uses her clout to stare down Big Pharma and win reparations for the countless lives ruined or lost due to addiction.

The film begins with Goldin’s protest on March 10, 2018, within the Sackler Wing of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, with the assistance of members of P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), the advocacy organization that Goldin founded to help fellow ex-addicts. Goldin and her team fill the reflecting pool in front of the famous Temple of Dendur exhibit with empty opioid bottles and lay down pretending to be dead as the slogan “Sacklers lie, thousands die” fills the air.

Other protests soon follow, including actions at Harvard University in Massachusetts, the Louvre Museum in Paris, and the Guggenheim, also in Manhattan. The latter generates one of the film’s most indelible images. A leaked memo from the Sacklers detailed that they wanted to cover the United States in a “blizzard” of OxyContin prescriptions.

Goldin and other P.A.I.N. protesters recreate this ominous proclamation to shattering effect as they rain down thousands of prescriptions into the iconic atrium of the Guggenheim. The demand of Goldin and her collective is simple: elite institutions of the world must sever ties with the Sacklers, reject their donations and remove their names from their buildings.

These fairly recent protests are a part of present tense history and were widely covered in the news. Audiences might not find these sections of the film to be insightful if they were contemporaneously reading about these events. Thankfully, the film includes plenty of never-seen-before material, mainly from the numerous P.A.I.N. planning sessions held at Goldin’s apartment, where they strategize about their next actions.

While this storyline has obvious appeal due to its David v Goliath dynamic, this is also the portion of the film that most plays like a conventional “documentary,” with talking heads, voiceover, real life footage, and so forth. Based on the original plan of the film by Goldin and P.A.I.N, this might have been all we would have gotten.

When Poitras came on board as director, she made the creative decision to expand the scope of the film and include Goldin’s life and times as a counter to her activist work. Poitras contended that Goldin’s life necessitated an “epic film.” It is this “Beauty” track of the film which eventually helps All The Beauty and The Bloodshed transcend its documentary roots.

The daring, formal gambit of this portion is that it is almost entirely composed of still images taken by Goldin. This approach works because Goldin photographed her own life -- with her family, friends and acquaintances -- in great detail. She initially faced pushback as to why a photographer’s own life would be a worthy subject of pictures. But the startling intimacy and lifelike spontaneity captured by Goldin dispel any misgivings.

Poitras layers these images with Goldin’s voiceover recounting the most pivotal moments of her life. Goldin frankly charts her miserable childhood in a broken home; her sister Barbara’s suicide; her years of hustle as she did waitressing and odd jobs to fund her post-bohemian lifestyle; her descent into strip shows (she says she danced in New Jersey because, unlike New York, you did not have to bare your breasts); and eventually prostitution to get by. She includes anecdotes like having to pay a cab driver once with a blowjob instead of money.

There are also interesting stories about Goldin and her friends pioneering the underground queer subculture, with its non-conformity, sexual freedom, free love and drugs. Several recognizable names pop up as supporting characters in Goldin’s life story.

There’s filmmaker John Waters and the star of his early films, actress Cookie Mueller. Goldin reminisces at length about Mueller, her love affair with a woman named Sharon Niesp, as well as her marriage to a man named Vittorio.

We meet photographer David Armstrong, whom Goldin brands the love of her life even though he was gay and she is bi-sexual. She reveals it was Armstrong who named her “Nan.” And then there’s Brian Burchill, her straight male ex-Marine lover for a large part of the 80s.

Goldin dwells at length on her amour fou with Burchill that ended ruinously in violent domestic abuse, with Burchill brutally punching her face and smashing the bones around her eyes. Goldin nearly lost an eye; her decision to release the picture of her battered visage was path-breaking as it made domestic abuse survivors feel represented in contemporary art for the first time.

The cornerstone of Goldin’s output were her famous photoplays that she put on, first for friends, and eventually for the public. These “slideshows” consisted of carefully selected pictures that she would pair with a curated playlist of music.

Audiences found these photoplays incredibly cinematic, as the pictures would accumulate detail and tell a story, and the people appearing in them would transform into characters. Poitras' decision to thus construct these sections of the film as “slideshows” of Goldin’s pictures smartly mingles Goldin’s life and artistic technique into a unified whole.

It helps that the pictures are enormously appealing . They are candid and dream-like at the same time, stripped of all vanity and pretense. They often feature graphic, full-frontal nudity -- male and female, erect penises nd even outright sex acts in frank detail.

Goldin contends she always gave her friends a veto over which of their images could be shown because she wanted them to feel proud of their pictures. She said once a female friend objected to images of her having sex with her boyfriend being shown to the world, Goldin stepped in and started photographing her own sex acts with her lovers.

The parallel tracks of All The Beauty and The Bloodshed collide in 1989, when Goldin was invited to curate an exhibition charting the HIV/AIDS crisis and the government’s indifference to it. Artist David Wojnarowicz wrote the incendiary catalog essay that excoriated the Archbishop of New York John O'Connor and Senator Jesse Helms for their harmful rhetoric. But little governmental action followed.

Goldin suffers devastating loss as several of her friends succumb to AIDS, namely David Wojnarowicz and Cookie Mueller, among others. Poitras thus crystallizes how a straight line can be drawn from the artist to activist. When the stakes are high, the personal and the political inescapably converge.

The greatest art that the most perceptive artists will produce in their lifetime is their own life and the way they have lived. Such is the case with Nan Goldin. And Laura Poitras’ All The Beauty and The Bloodshed captures that with grace and equanimity.

The film premiered at the Venice Film Festival 2022 and is now playing in North America via Neon. Visit the official site for more information.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.