Review: Criterion Rediscovers THE LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM

Volker Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta’s tense German political thriller gets a much-needed high-definition upgrade.

On a sea of uncertainty rocks a dark, clandestine encounter between a man and a woman. Their passion is palpable; as palpable as their risk in following up on it. Though alone, their affair will soon be the news of the world. It’s Germany circa mid-1970s, a time of no-tolerance in terms of political dissent. Unfortunately for Katharina Blum, she’s fallen hard for a most-wanted revolutionary.

The scene, a “meet-hot” of the central, soon-to-be-separated lovers, is a flashback, occurring well into the story. Visually, it is shot as a slow dolly-in, subtlety cascading back and forth between the two as they speak affectionately in hushed tones. Knowing what we know by then, it plays as intended: as a most tragic memory interlude; the camera work and the atmosphere signaling the unbearable and uncontrollable turbulence to come.

As co-directed by Volker Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta, and adapted from a novel by the prominent Christian progressive Heinrich Böll, 1975’s The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (Die verlorene Ehre der Katharina Blum) is an unsettling, under-the-skin kind of work. Undeniably topical in its conception and execution, it’s quite curious as to how and why the film has aged most effectively.

A relatively early product of the New German Cinema movement, one intended to flag the hypocrisies and dangers within the country’s stubbornness in facing its then-fairly-recent fascist past, Katharina Blum unflinchingly zeroes in as a political thriller the way Three Days of the Condor or some such comparable stateside work would, sans the outward moralizing. Like the title character herself (played with distinct undistinction by Angela Winkler), what renders the film so grippingly uneasy is its refusal to make any distinct proclamations, to the degree that the door of Blum’s perceived guilt is propped open throughout by the filmmakers. To everyone’s specific creative credit, narrative tells are few and far between.

As pointed out in the handful of bonus interviews included on this Criterion Blu-ray (all of which are carryovers from the company’s 2003 Blu-ray release), the aggression sources against Blum is three-pronged: the police, the press, and people. The police, headed up by the thoroughly intimidating and physically striking Kommissar Beizmenne (Mario Adorf), are quick to raid and to presume her a guilty accomplice of assisting her lover Ludwig Götten (Jürgen Prochnow) in his accused terrorist actions, including but not limited to bank robbery, a key word being “accused.”

The state-compliant press goes as low as low can go in its own pursuit to paint Blum as some sort of terror-enabling nymphomaniac. From that, the public responds thusly, as Blum becomes the recipient of all manner of sexually threatening anonymous notes and derogatory comments. Indeed, she is in every way guilty until proven innocent of falling for a man that law-and-order Germany cannot abide.

As photographed by Jost Vacano (RoboCop), Katharina Blum is in turn both poppingly colorful and oppressively drab. As Vacano explains in his brief interview, the palate was entirely by design, though every moment of the film was shot on practical locations. Filmed during the annual German Carnival season, the streets full of clown-wigged revellers make for a festively weird dichotomy to the central plot, kind of a sideshow nightmare that Blum is mired in. As much as anything else, the tactile grit and immediacy of the world that Schlöndorff and von Trotta depict is central to the overall effectiveness of this timely yet timeless piece.

Criterion’s 2020 Blu-ray presentation of The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum, sporting a new 4K digital restoration, is head and shoulders over the look of the 2003 DVD edition. As mentioned, all the supplemental material is ported over from the seventeen-year-old release.

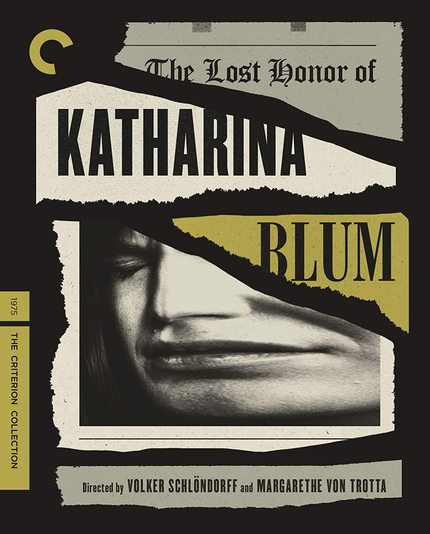

Much-improved transfer aside, the newest aspects this Blu-ray upgrade are film critic Amy Taubin’s much-expanded essay (included in the printed insert) and the new cover art by Joan Wong. Though some may prefer the ransom note aesthetic of the new cover, I must admit an affinity to the dread-inducing starkness of the original DVD’s packaging. Wong goes so far as to literally smear the main character across a faux-tabloid cover. For a movie that’s so deliberately elusive, it’s far too on the nose.

These are the Blu-ray bonus features in detail:

• Interview from 2002 with directors Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta

• Interview from 2002 with director of photography Jost Vacano

• Excerpts from a 1977 documentary on author Heinrich Böll

• Trailer

The fundamental uneasiness of The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum is, at first glance, amplified in 2020. As today’s voices of reason are made to argue the validity and necessity of a free press -- as flawed and slanted as it sometimes shows itself to be -- a story that ends on a deeply cynical note of rebuke against the German version of the institution is something to properly recon with.

As tempting as it is to point out that the antics of The Paper in the film is the product of what was a deeply state-compliant press in that time and place and leave it at that, the stingingly hollow words of the ending, proclaiming the free press as the vital instrument to democracy that we see it as today, muddy things just so.

But a political film that wraps up free of challenge is not a film with a future. And to be sure, back in the day, Schlöndorff’s contemporaries warned him that Böll’s source novel was perhaps too of-the-moment. That warning proved unfounded, as the enigmatic resonance of Katharina Blum, for better artistically or for worse circumstantially, persists undoubtably in the current Trump era. As today’s fascistic leaders work overtime to brand peaceful social justice protestors as vandalism-obsessed hooligans, this film demonstrates an even more volatile moment when leftist activists were truly violent- and segments of the population nonetheless argued for justice for them.

Reinforcing the activist’s need to act out in the first place is the fact that there was no such due process for many upon arrest. Hence, the soul-killing resort to the words of Bertolt Brecht: “Violence helps where violence rules.” If the upcoming U.S. election has anything to say about the future (and it quite certainly does), may we never arrive at such an ending -- the very opposite of fine.

The film is available on Blu-ray and DVD in separate editions from The Criterion Collection.