HEATHERS Interview: Michael Lehmann On The 30th Anniversary Of His Black Comedy And Why Donald Trump Ruined Satire

Life in high school can be rough, as social distinction is pretty much inevitable.

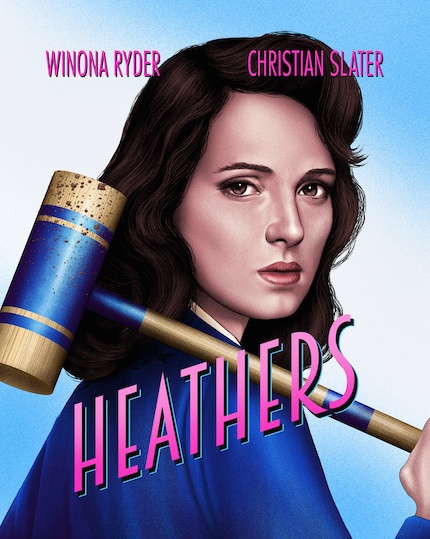

In Heathers, the protagonist Veronica (one of Winona Ryder’s first roles) is trying to get along with the most powerful clique at her high school in Ohio. This clan is leaded by three girls that share the name Heather, particularly by Heather Chandler (Kim Walker), an egocentric, superficial and popular bully.

Though Veronica hangs out with the so-called Heathers, and helps them out to fulfill their cruel pranks against the unpopular students (using, for example, her ability to copy other people’s handwriting), at heart she despises everything that Heather Chandler stands for. On the other hand, Veronica is very much attracted to outcast J.D. (Christian Slater’s breakthrough performance), the new boy at school who’s not intimated at all by the bullies.

Heathers takes a dark turn as Veronica and J.D.’s intentions of giving Heather Chandler and the other assholes (including a couple of football players) a taste of their own medicine get out of control. Murder, teenage suicide, repressed homosexuality, a young and manipulative psychopath and his plot to blow up an entire high school, are among the subjects in Michael Lehmann’s controversial black comedy Heathers.

The release of a brand-new steelbook Blu-ray, which conmemorates Heathers' 30th anniversay, was the perfect occasion for Lehmann to recall his cult classic, and my conversation with the director precisely started by tackling the mentioned dark themes of the film...

ScreenAnarchy: HEATHERS has a classic high school setting that’s still popular in Hollywood movies, however your film has darker themes that we basically don’t see anymore in mainstream cinema. Do you think HEATHERS could be made today?

Michael Lehmann: No! I think it would be very hard to make the film today, but I have to remind people that it was a film that really couldn’t be made when it was made. We were just lucky, we figured it out.

First of all, Dan Waters’ script was really good. Second of all, it was a time in filmmaking when people were willing to make almost anything if they thought it could helped fill the shelves in video rental stores. So we were able to find a way to get the movie made in spite of how dark it was. And it was still practically impossible, we had one company that was willing to do it and that was it.

Today you have a much harder time because violence in high schools, high school shootings and that sort of thing, makes that kind of subject matter particularly difficult for comedy.

Now that you mention it was very difficult back then, what was the main challenge to get the film done?

Well, a lot of people read the script in Hollywood and said, “oh yeah, this is really funny, but we’re not making a movie like this. You can’t make a movie where high school students kill each other and you can’t make a movie where you’re dealing with the ‘issue’ of teenage suicide and make light of it.”

It’s never in the case that Hollywood or mainstream filmmaking has embraced the idea of doing satire nor have it ever embraced the idea of doing black comedy. It’s just not part of the culture here, you know? So a lot of people read the script and said “it’s good, but we’re not doing to make this.”

After reading the script, what was the thing that really made you fight for it?

I was very much into the kind of humor that was in the movie and very interested in making dark satire. I had come out of USC film school with a movie [The Beaver Gets a Boner] that was set in high school and had a very dark sense of humor, so I felt like I had sufficient to make the movie even though I was a first time filmmaker.

I think one of the ways we got it made was the guy who was running New World Pictures, his name was Steve White, had seen my student short and he kind of got the humor that I like to do and when we brought him the script to Heathers, he understood it and he said “I think you can really do a great job with this”, so he basically said “I’ll make it, but you still have to change some things.” We had to pull back on some darker elements, but he essentially said “I’ll let you make the movie.”

I’m always fascinated by Hollywood stars’ early roles. Did you think back then that Winona Ryder and Christian Slater were going to become stars?

I always felt Winona Ryder had genuine old-fashioned movie star quality.

When you pointed the camera at her, there was something about her eyes and her face and the way she acted that was perfect for movies. And so I never had any doubt that she could become a star.

Christian had a very unusual presence, especially when he was little because he was kind of like a pixie, he was not your typical male actor.

Aside from the fact that there was a heavy influence at that time from Jack Nicholson, which I thought was a little distracting, I still felt that he was a very, very talented actor and that he had the potential to become a real movie star.

You can see this, you’re not always right, but when you’re having a movie and you don’t have the money to put established stars in, you look at a lot of people and you use your judgement.

I read in another interview that you liked the movies by John Hughes but felt they weren’t representing what high school was really like. How was the approach to this subject with HEATHERS?

The John Hughes movies, which are very funny and really good, represent a kind of fantasy of what high school should be from a teenagers’ point of view. It doesn’t mean everything is light because the problems that the characters in John Hughes films face are: "I’m not going to go to the prom", "will anybody like me?" and that sort of thing. But the general feel of the John Hughes movies is big plus on rock ’n’ roll, big plus on the idea of rebellion, but essentially very down the middle mainstream, normal American kids being rebellious. And they’re a little sentimental. I like them, I won’t criticize them, I still think they’re great, but it wasn’t really what I wanted to do. I don’t think Heathers is more realistic, it’s just a different, darker take on what teenagers do to one another.

I think that’s why it has a cult status and filmmakers like Edgar Wright consider it as a favorite. How do you feel about this?

I love it. You’re always happy when anybody likes your work, it’s hard out there to get appreciation for anything. Other directors, they’re forgiving but they’re also hard on directors.

I’m waiting for Edgar Wright to admit that he stole the stuff from Baby Driver from Hudson Hawk [laughs]. He’s a great guy, by the way, and I love his films. I love Baby Driver and I don’t think he stole it from Hudson Hawk, but next time I see him I’m gonna tease him about it.

(In Hudson Hawk, Bruce Willis and Danny Aiello are a couple of cat burglars. In a very memorable heist/musical sequence, for example, we get to witness their peculiar method: they sing a song they know by memory –"Swinging on a Star" in this case– to track time while executing the heist. Therefore one could definitely argue that Hudson Hawk was an influence on Baby Driver.)

Going back to the current times in Hollywood, there was recently this quote by Todd Phillips, who said that comedy was killed by the so-called woke culture. How do you feel about this and the political correctness that’s going on in the industry right now?

It’s probably true, but it’s very complicated because with the [Donald] Trump culture, the kind of reactionary, bullying, politically incorrect behavior is being celebrated, that the balance has being lost. If you wanna make satire, you’re gonna have to cross boundaries all over the place. I don’t think audiences now can necessarily tell the difference or wanna tell the difference between humor like we used to do it and simply offensive behavior like we see from our political leadership. We’re kind of stuck. I blame Trump for ruining satire because he brings with him a level of self-parody that nobody else has ever done.

I agree.

But, you know?, it’ll change, it’ll change.