Interview: Adrián García Bogliano Talks SCHERZO DIABOLICO

After directing Late Phases, his English-language debut film, Adrián García Bogliano returned to Mexico to work again with Here Comes the Devil’s Francisco Barreiro.

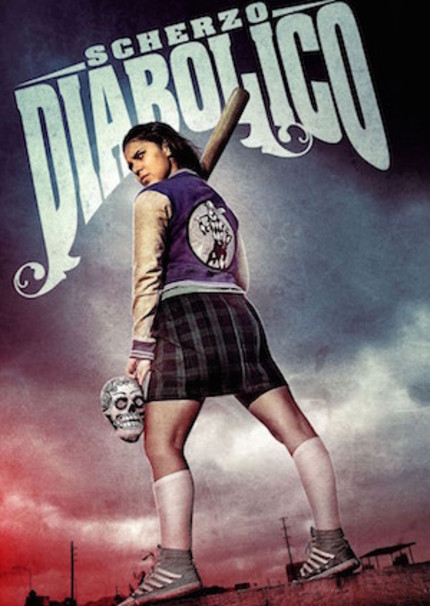

The result was Scherzo Diabolico, in which Barreiro portraits a middle aged man who -- while waiting for better circumstances at his work and also to put together his marriage -- will become the worst nightmare for a young girl (Daniela Soto), turning himself into an iconic masked psychopath.

Scherzo Diabolico is out today on VOD & DVD, so here’s part of a conversation I had with Bogliano back in early 2015 about his latest film.

What was the genesis of this return to Latin-American cinema after your English-language debut?

Adrián García Bogliano: While doing Late Phases, I used to read line by line with the screenwriter, and I asked him about the meaning of each line in order to have a notion about his intentions. The whole process was very different for me, so I really wanted to make something personal again.

The genesis of Scherzo Diabolico was quite simple: I met a producer back at Fantastic Fest 2012 who wanted to work with me. When another project I had didn’t come together, I talked with this producer and the rest was quick.

I had already a version of the script and just did some rewrites with some autobiographical ideas that I collected over the years. The idea was to make a film in which friends could collaborate with me.

Pablo Guisa came first for a cameo, and then became associate producer. Lex Ortega is my obvious choice for sound when I work in Mexico. I always wanted to work with Jorge Molina and we saw the opportunity to have him fly from Cuba to play the Granosvky character as a wink for genre fans.

As for Paco Barreiro, I thought he was extraordinary since Jorge Michel Grau’s Somos Lo Que Hay. I called him for ABCs of Death but he couldn’t make it; then in Here Come the Devil, he made his character shine.

Music is a key element in SCHERZO DIABOLICO. Do you consider this film as the union of your two passions (music and film)?

I still love music; actually I have my radio show dedicated to cinema and music. The element that really put all the pieces together was the “Scherzo Diabolico” piece; listening to that tune gave me a clear direction.

I liked the fact that this was an independent film but with an epic element: the great classic compositions, some very recognizable, others more obscure. I’m not a big connoisseur of classic music, but I did the research trying to find the best material, even some material that’s not typical.

When you decided to work with a psychopathic character, a well-known theme in genre cinema, what were the challenges to make it unique?

I’m interested in making people understand the villain, whoever it is. It defies certain rules of the genre where the bad guy is the bad guy and that’s it; I try to make you at least understand the villain’s thinking.

Paco Barreiro’s character can cause empathy, and that’s dangerous because it’s not the right thing. But cinema must ask uncomfortable questions.

It’s an interesting time, women in general are gaining a place in genre cinema, but there’s also an absurd dose of political correctness. I hear producers saying that they can’t do anything with a movie because it has a chained girl, which for me is absurd. If you say a girl can’t be tied you have to leave out The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, one of the greatest films in horror history.

Daniela Soto was a delight; it’s really difficult to find someone that can have a positive attitude during the whole shooting. She’s very serious towards her work, and this was her first major role. It was quite difficult for her, because the margin in which the actors could move was very precise and small. She had to transmit everything through her face.

Do you think people identify with Barreiro’s villain because he represents the inherent frustration of a regular day job?

I’m convinced that many things arrive late to your professional life, but we have the idea that because we’re young everything must happen now. Many 40-year-olds have a crisis because they want to succeed, there’s urgency to achieve things.