Fantasia 2013: A Rough Guide to Parsing Miike's Hybrid Thriller SHIELD OF STRAW

As I was watching Miike Takashi's police thriller Shield of Straw during its opening night presentation at Fantasia, I started to wonder if the director of dozens of gonzo filmic insanities had finally succumbed to the temptation of making a polished, Hollywood-style blockbuster.

That's similar to the alarm bells rung by our own Brian Clark when the film debuted at Cannes. In his review, he discussed some of the "many ways in which [it] falls short of being the knockout that it could have been." Among other things, he asked, "What has happened to Miike Takashi? The man who was once able to inject even the most cliche genre stories with wackiness, visual pizzazz and spontaneity seems totally on auto-pilot here."

It's a fair point. After further consideration, though, I think it helps to examine its various Japanese and American antecedents in order to make sense of the film's deceptive mash-up of conventional big-budget action and morally ambiguous melodrama. Click through the pictures to consider some of those antecedents.

The story of Shield of Straw involves a serial killer in police custody. Two ambitious special Police Force officers trying to transport him across the country for his trial. One of the victims, a young child brutally raped and killed, is from a rich family, and her surviving grandfather publicly announces a massive cash reward for anyone, cop or civilian, who manages to kill the serial killer.

Tackling the high concept action-thriller, the bread and butter of Hong Kong cinema as well as Hollywood before comic book movies and endless sequels seemed to take over in the past decade, is a first for the director. Seeing the WB shield appear during the screening was a surprise. Cynically, one might wonder if the studio bought the rights to hold the option on an English remake of an admittedly excellent high concept.

There is a juggling around of pacing, genre beats, and even ambition that makes Shield of Straw work in a pretty fascinating way after you settle in to its particular modulations. A major wrinkle is that the grandfather, a billionaire financial type with no other relatives and a wasting disease will pay even if they do not succeed. This make a handsome pay-out likely even for an unsuccessful attempt. Miike and his screenwriter (and the likely source novel) focus on the clash between duty, morality, ethics and how people rationalize the imaginary line between urban desperation, depravity and greed. What other films have have set these sorts of precedents? Onward.

In Seven, the city exists as an endless compost heap of moral decay, indifference and flat out nihilism. Shield of Straw may not feature all the rain and visually rotting aesthetic of David Fincher's masterpiece, but it does have a similar worldview in that the entire ecosystem is counterproductive to two policeman doing their job. Everything is suspect, particularly when John Doe gets to play out the last link in his chain of depravity in a perverse and sick fashion.

Our two lead two cops have an entire city, including almost every layer of authority, playing an active role in trying to kill the suspect. The will of authority is besieged by the very collective that sets its trust in it. For the pleasures of surprise, I will certainly not spoil the outcome of either film, but how they get to this point is both similar and radically different.

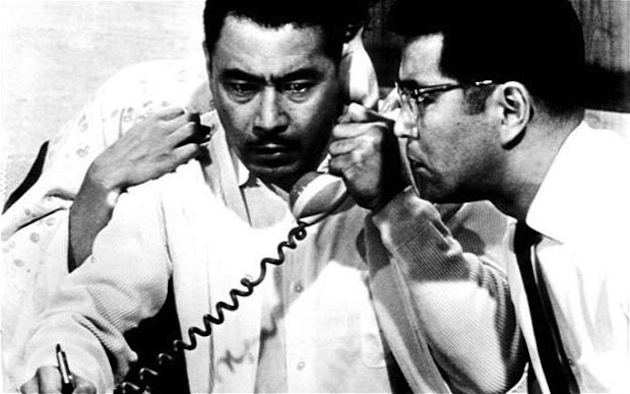

Miike's film is not as good as the masterpiece on money and morality, High and Low, but a director like Kurosawa Akira sets a pretty damn high bar. That being said, Shield of Straw at its best moments aspires to this pinnacle by mixing of social drama, chase thrills and procedural detail. Instead of a ransoming chauffeur's son's return from kidnappers, funded by his boss' money in Kurosawa's film, we have millions of people in Japanese society in the financial hole of personal debt pining for millions of dollars on offer to murder of a man that society finds abhorrent. Not the exact same question, but how we sort our personal ethics and fiscal responsibilities out in public while under extreme social pressure are the focus of each film, one using a realist style in the early 1960s, the other using a much more modern style 50 years later.

Shadows of the sense of duty and honour of Samurai cinema also haunt High and Low, and they certainly haunt Shield of Straw.

In John Carpenter's cult classic The Thing, a bunch of professionals are boxed into a situation where an alien force can mimic anyone and can transform otherwise responsible people into 'the other.' This kind of paranoia in the face of reason (and stressful conditions) makes for great drama, whether there is a gory shapeshifter in Antarctica or it is simply a bunch of cops from different departments in a convoy (or a bullet train) en route to Tokyo.

Just as the researchers in The Thing devise various psychological and physical tests to find out who is corrupted and who isn't, many of the best moments in Shield of Straw feature the suspicion of our main cop-protectors testing various working professionals on their intentions. And like The Thing, we can never even be sure if the the two main heroes are or are not corrupt themselves.

The casting of Shield of Straw is delicious on a meta level involving two seminal Japanese genre-film classics. First taking the reporter, and aunt to one of the victims of the ghost), in the ultimate expression of Japanese paranoia and nihilism, 1998's J-Horror classic Ringu and casting the actress Matsushima Nanako as one of the two key protectors, Shiraiwa of the serial rapist and killer, Kiyomaru.

In Ringu, once a person has viewed the demonic video, they cannot 'unsee' it and are doomed to die. Fear of technology and a cynical lack of restraint of the bulk of the population lead to horror and death. In Miike's film, this unease and paranoia of the core team of police protectors need to both rely on and shun the technology.

Shiraiwa needs to know what the rest of the world can see on the internet regarding their location and method of transport which seems impossibly aware of their coordinates at all times. This is possibly due to a bugged cellphone or GPS tracking device on a police officer, but it cannot be located. She has everyone give her the batteries of their cellular phones, but she herself cannot help but keep coming back to the technology, even for more mundane uses. Technology (and the speed at which information travels) in this high speed chase is the source of and solution to many of their problems. Shiraiwa cannot help but keep fiddling with her phone even as she has confiscated everyone else.

In Kinji Fukusaku's subversive satire, Battle Royale Fujiwara Tatsuya plays young Shuya, the most morally upright and emotionally affected student in a class of roiling hormones and issues, that is whisked to an isolated island, and forced to kill each other for the pure spectacle (and catharsis) of the nation.

In one of the best pieces of subversive casting in some time, the same actor, now 15 years older than the grade 9 student in but still with a wholesomely smooth face plays Kiyomaru as the vile, almost assuredly guilty killer and defiler of a 7-year-old girl. It is implied that he has done this to many others as well. Kiyomaru grovels, whines and otherwise prostrates himself to the police protection he is offered. At the same time, every time a citizen (or cop) is harmed or killed by making a play to kill him, Kiyomaru sports a wicked half-smile, gleeful in his culpability.

The actor still imparts some human qualities (he tries to care for his mother in a way) and seems conflicted (shades of Peter Lorre in M) about his compulsions. But otherwise Fujiwara Tatsuya perfectly inverts his most famous image into something twisted and ugly and difficult to empathize with on every level. An attempt to further erode a moral reaction inside the film or outside to the audience, even with his smooth still boyish face.

OK, this is put in here quite shallowly, mainly because it amuses me (perhaps only me.) The timeline of Shield of Straw involves aborted travel attempts on planes, trains, and automobiles, with Kiyomaru, his two officer-protectors, eventually walking in the blasting heat before a final confrontation with the 'mob boss' (here the grandfather of Kiyormaru's last victim who offers the nationwide bounty) as well as all various police bosses, bureaucrats and such, is oddly similar in both structure and stop-start pacing to Martin Brest's 1980s buddy comedy Midnight Run.

The odd couple friction between with Robert De Niro and Charles Grodin during their road trip as they learn to come to grips with opposite personalities, and personal history, is played between the two cops and their work methods, and yes, their personal histories in Shield of Straw. This is, of course, a beyond-ridiculous leap to say there was any influence of a rather obscure little comedy (totally opposite in tone and intent) on the film here. I am sure it is all coincidence and similarities are totally spurious. Forgive my indulgence, but take a moment to chuckle about it. The idea of Miike making a buddy cop road movie is appealing to me. This appears to be as close as we will ever get ... but you never know.

The exception that proves the quality of the film is this one last thing, the final shot of Shield of Straw is, as Brain Clark aptly puts it, "an extremely bold note that's honest, hopeful and scathing all at once." And the film definitely goes out on a high note for the genre of which I happily can find no immediate analogue. The last puts the capper on a film that upon reflection, is a hairs breadth more than the sum of its parts.

For all its surface gloss and studio look, don't let Shield of Straw fool you into thinking there is nothing going in its action film brain. This one is most assuredly worth your time.

Around the Internet

Recent Posts

Leading Voices in Global Cinema

- Peter Martin, Dallas, Texas

- Managing Editor

- Andrew Mack, Toronto, Canada

- Editor, News

- Ard Vijn, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Editor, Europe

- Benjamin Umstead, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, U.S.

- J Hurtado, Dallas, Texas

- Editor, U.S.

- James Marsh, Hong Kong, China

- Editor, Asia

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana, New England

- Editor, U.S.

- Ryland Aldrich, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, Festivals

- Shelagh Rowan-Legg

- Editor, Canada