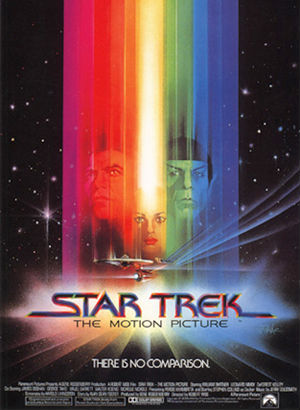

70s Rewind: STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE Still Goes Slowly Where No One Wants to Go

In December 1979, Star Trek: The Motion Picture was a major letdown.

Earlier in the decade, a handful of my school friends banded together to form the Science Fiction Club. Initially, we discussed Isaac Asimov's Foundation trilogy, Ray Bradbury's stories, and other disrespected literary works. We rode our bicycles to the nearest branch of the public library, and often stopped by a nearby used paperback book store, where we carefully examined the science fiction shelves -- they were low, near the floor, and we had to sit on our haunches, but we were young -- and picked out what we could afford on our tiny allowances. (The owners were always kind and appreciative of our regular patronage, no matter how few pennies they made from us; they were among the few adults who encouraged us in our appreciation of science fiction.)

We loved The Twilight Zone, hated Lost in Space, and were horrified by the stupidity of The Starlost, but we still watched everything, because there wasn't very much science fiction on television in those days, and you got it where you could. So we watched the original Star Trek series in syndication, and we bought books about it, and we ridiculed the silly episodes and praised the good ones, and we made fun of the animated TV series, but we still got up on Saturday morning to watch it.

One of us cut school to see Star Wars on opening day, and we were all jealous of him, but he was angry because he hated the ending, which was stupid 'because they let the Darth Vader guy get away, and they didn't show what happened to him.' (Later, he attended Stanford University and became an engineer, highly respected in his field.) Still, two of us waited for three and a half hours on a warm Saturday afternoon in Westwood, California, and we grabbed the last two seats in the back of the auditorium, and we gasped at the opening sequence and the surround sound, and we cheered and yelled like everybody else, and we counted ourselves lucky to be alive to see science fiction done right on the big screen. (Later, my friend became a pothead; the last time I saw him, years later, he was happily shelving books in the same branch of the public library where the Science Fiction Club had once met.)

Two and a half years later, I was no longer a kid and thought myself wiser to the ways of cinema. I'd started seeking out classic Hollywood movies and foreign language films that played on the repertory circuit in Los Angeles -- the late 70s were a great time for educating yourself in cinema history -- and reading serious film criticism on a regular basis. My love for science fiction remained, though it was getting crowded out by other interests. Still, I kept up with as many related titles as I could: Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Damnation Alley, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Superman, and, earlier in 1979, Nicholas Meyer's rather daring Time After Time, and the disastrously bad Meteor.

Two and a half years later, I was no longer a kid and thought myself wiser to the ways of cinema. I'd started seeking out classic Hollywood movies and foreign language films that played on the repertory circuit in Los Angeles -- the late 70s were a great time for educating yourself in cinema history -- and reading serious film criticism on a regular basis. My love for science fiction remained, though it was getting crowded out by other interests. Still, I kept up with as many related titles as I could: Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Damnation Alley, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Superman, and, earlier in 1979, Nicholas Meyer's rather daring Time After Time, and the disastrously bad Meteor.

Nothing prepared me, however, for the crushing disappointment of Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Perhaps it was because my expectations were too high; I was by no means a Trekkie, but I had only minimal expectations that any of the science fiction pictures of the time would be any good, and was always happy to be surprised. I expected much more from Star Trek. (Orson Welles narrated the teaser trailer! Isaac Asimov was listed as science consultant!) It was glacially slow, featured familiar characters who were uncommonly stiff, and the special effects "journeys" made it feel like 2001: Space Odyssey: Yes We Saw That. And the resolution, the big, earth-threatening "issue" that addressed a big, philosophical idea? Ridiculous. I rolled my eyes in disbelief that I'd been foolish enough to expect more.

Years passed. The theatre where I saw it -- Mann's Chinese 2 or 3, adjacent to the original in Hollywood, California -- closed and was demolished in 2000. The following year, a new DVD was released, featuring "the director's edition." Many fans rejoice, claiming that director Robert Wise has created a demonstrably superior version of the film. Eight years later, the film is released on Blu-ray, but only in the original theatrical edition. (It is claimed that the additional / replacement special effects created for the 2001 "director's edition" were only rendered in standard definition.)

Finally, perhaps, all my memories of the original, deadly dull screening have dissipated to the point that I can watch the movie again with an open mind.

Alas, the theatrical edition of Star Trek: The Motion Picture remains stillborn, with only occasional moments in which it threatens to come to life. But at least now I have a better idea why.

Robert Wise famously edited Citizen Kane and others before moving into the director's chair, where, like any good studio director, he specialized in variety. He made the great science-fiction drama The Day the Earth Stood Still and the great horror film The Haunting, as well exciting, dark thrillers like The Set-Up and The House on Telegraph Hill. He even made office politics look thrilling in the oft-electrifying Executive Suite.

In the 70s, Wise made The Andromeda Strain and Audrey Rose, genre efforts that showed he still had a feeling for science fiction and horror. He approached Star Trek: The Motion Picture with a similar touch; as in The Andromeda Strain, he utilized a split-focus diopter multiple times, introducing greater space and classicism to otherwise ordinary scenes of dialogue. But it wasn't appropriate for the Star Trek characters that we'd come to know; it made individuals look more like the U.S. Presidents on Mount Rushmore. Also, it tended to divide the characters from each other, playing havoc with the concept that they were all seasoned crewmates who considered each other to be friends. These were not friends; these were icons.

In the 70s, Wise made The Andromeda Strain and Audrey Rose, genre efforts that showed he still had a feeling for science fiction and horror. He approached Star Trek: The Motion Picture with a similar touch; as in The Andromeda Strain, he utilized a split-focus diopter multiple times, introducing greater space and classicism to otherwise ordinary scenes of dialogue. But it wasn't appropriate for the Star Trek characters that we'd come to know; it made individuals look more like the U.S. Presidents on Mount Rushmore. Also, it tended to divide the characters from each other, playing havoc with the concept that they were all seasoned crewmates who considered each other to be friends. These were not friends; these were icons.

Wise was not familiar with the original series, and by the time he came on board the project, the script had already been through numerous development cycles. Work began in 1975, but was halted as a feature film project in May 1977, without a script satisfactory to the studio. The project was turned over to the television division, where a treatment by Alan Dean Foster was turned into a teleplay by Harold Livingston. Six months later, after the double triumph of Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the project reverted to the feature film division, and the teleplay was revised into a screenplay that went through many changes. Production began in August 1978 without a finished script.

Reportedly, the visual effects were a nightmare, with the first company hired unable to complete the work. The delays meant a greatly accelerated schedule for the replacement artists led by Douglas Trumbull (who was actually the first choice but had passed). Wise blamed the rushed post-production schedule and delays in visual effects and felt that what was released represented only his "rough cut."

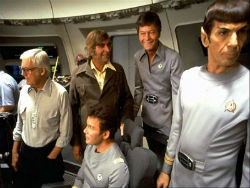

Even if Wise had all the time in the world, he would not be able to salvage this particular wreck. In this first filmed version, the Enterprise crew members are strangers to one another; there is no chemistry, almost no friendly banter, no sign that they lived and worked and slept under the same roof for years at a time. They are on an adventure, but not one that any of them particularly cared about. They are reduced to being passive observers, for the most part, letting things happen and occasionally wondering what it all means. There is no sense of urgency.

Even if Wise had all the time in the world, he would not be able to salvage this particular wreck. In this first filmed version, the Enterprise crew members are strangers to one another; there is no chemistry, almost no friendly banter, no sign that they lived and worked and slept under the same roof for years at a time. They are on an adventure, but not one that any of them particularly cared about. They are reduced to being passive observers, for the most part, letting things happen and occasionally wondering what it all means. There is no sense of urgency.

The filmmakers made a mistake that we recognize more easily today, in view of the veritable flood of remakes and reboots that we've experienced since 1979. The mistake is that they rebooted Star Trek without recapturing what made the original series memorable. No one watched the original show because of the special effects, or because of any deep philosophical issues that were occasionally raised in an oblique, meek manner.

We watched because Star Trek was a pioneering workplace comedy-drama, and we didn't even know it. But we knew any place where all the employees got along and the boss could be pretty cool as long as you did your job was a place where we were happy to spend some time. And the first movie adaptation missed that entirely.

70s Rewind is a column about the writer's favorite movie decade.