DREAMS 4K Review: Criterion Honours Akira Kurosawa with Inaugural UHD

Earlier this year at the Cannes Film Festival, 80-year-old Martin Scorsese told Deadline that he finally understood the words of Akira Kurosawa who, upon accepting his honorary Academy award in 1990, said: “I’m only now beginning to see the possibility of what cinema could be.”

This was indeed a curious statement coming from such a renowned cinematic pioneer; a true original who time and again set narrative foundations that generations of filmmakers would spend lifetimes building from. It had been almost 40 years since he’d redefined the possibility of narrative storytelling with Rashomon and almost as much time since establishing the groundbreaking artful orchestration of Seven Samurai’s action, and yet it wasn’t until 1990’s Dreams that Kurosawa would feel he came closest to understanding the essence of cinema.

Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams was not a film that the legacy maverick was able to fund in his home country, and it wasn’t particularly well-received upon its release. Patronizing critics of its day dismissed Kurosawa’s potential swan song as an overly didactic indulgence (pessimists, the lot of them!). And although time has been far more generous in its ever-evolving reevaluation, it still took the Criterion Collection until 2016 to shine its lovelight on Dreams, after having, at that point, already released 25 of the director's films.

That said, the 2016 release of Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams came far better late than never with a wealth of priceless supplements, and this year Criterion has more than made up for lost time by bestowing upon Dreams the honor of being the first Kurosawa film to enter the UHD collection. In my impassioned opinion, this is a most befitting choice, and to celebrate the occasion of its 4K indoctrination, I opted to splurge on a UHD projector in order to see some of my all-time favorite images ever committed to celluloid on as big a screen as possible with the most pristine presentation available. The experience did not disappoint.

From a narrative perspective, Dreams is a vivid stream of fevered consciousness that collectively forms a reflection of existence as dreamed by an artist in the final stages of his life. Inspired by Natsume Soseki’s Ten Nights of Dreams, Kurosawa’s eight shorts act as a psychobiography detailing his life in surreal analogy, from the young boy who bears forbidden witness to a fox wedding, to the adult wanderer who encounters the funeral celebration of a humble villager.

The dreamer, known only as ‘I’, dons Kurosawa’s trademark bucket hat so as to leave little doubt as to who I represents. Though of course, I can only refer to the storyteller, as in the case of Soseki’s book, in which each chapter begins with the line, “This is what I saw in my dream...” However, in Kurosawa's telling, the protagonist is infused with a passive sense of ‘the hero's journey’ as defined by Noe theater, where the protagonist tends to act primarily as a witness; not unlike how the dreamer is powerless to affect what s/he encounters while dreaming.

As we learn in Bilge Ebiri’s essay, 'Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams: Quiet Devastation', featured in the package’s booklet, “The scholar Zvika Serper has discussed the influence on the role of I of Noh theater — 'In most of the plays, a waki . . . usually a traveler, visits a famous place where he encounters a local inhabitant, the shite . . . and asks to be told the story associated with the place,' Serper explains. 'In Dreams, I’s character is revealed through the waki, who in each dream encounters a different shite performing his own story . . . [The waki’s] acting, therefore, is kept to a minimum.'”

If the film tells any semblance of a story, its aim is nothing short of detailing an entire lifetime, at least as represented by eight of the dreamers' most resonant impressions of living on Earth in the 20th century. As aforementioned, Dreams begins with I as a mischievous child disobeying orders to watch a secret fox wedding, only to be discovered and consequently cast out into the wilderness of existence carrying only a hara-kiri blade to use should he fail at his destiny.

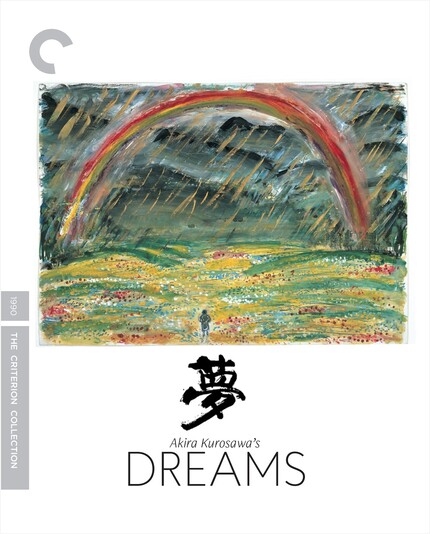

This image of the lone boy walking head-on into the mountain-strewn yonder, further beautified by a large rainbow (care of Industrial Light & Magic) is the one that Kurasawa chose to represent the film, as if to say that an aspirational life is a solitary journey that requires both courage and fortitude. With his instrument of death at hand, the stakes of I’s dreams are life and death.

From there, I comes to learn of deep grief through the manifested spirits of a peach orchard, of determination against overwhelming odds through a blizzard worthy of a snow demon, of wartime atrocity from the ghosts of a needlessly killed platoon, of manmade scientific catastrophe through an Ishirō Honda-style disaster flick (in a dream that seems to eerily foresee the Fukushima disaster), of the apocalypse through post-nuclear damnation, and finally, and most potent of all, of a return to nature through the death of a 100-year-old villager in a simple land that time forgot.

The film’s script was penned and illustrated solely by Kurosawa, which marks the first time the auteur dove into the bones of a story unassisted since the 1940s, and perhaps for this reason, Dreams evokes the passion of an aged artist giving himself to his muse with urgent abandon. Full of dreamily vivid sets inspired by the artificiality of Noe theater designs, as well as beautifully composed frames, each one a work of art in itself, the dense imagery of this film is both visually and poetically dazzling, not to mention profoundly moving.

Kurosawa’s subjects, though autobiographical and uniquely Japanese to be sure, are sagely universal, but there is nevertheless much to be gleaned from listening to film scholar Stephen Prince’s commentary to appreciate the ‘Rosebud’ specifics of Kurosawa’s life which he chose to meaningfully incorporate. Off the top, there is the hara-kiri instrument which young Akira was actually given as a child by his mother. Then there is the tragic loss of his much adored older sister, who he lost at an early age, thus informing his young spirit with a lifelong sadness that he would depict in the film’s gloriously bittersweet peach orchard segment.

All of the 2016 Criterion supplements are rich and essential additions to the big picture that is Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams. On top of the aforementioned essay by Bilge Ebiri, the booklet also features Kurosawa’s unfilmed script for the ninth dream, which I for one believe the film is much stronger without. Meanwhile, the interviews with longtime production manager Teruyo Nogami, as well as the newly initiated (at the time of its production) assistant director, Takashi Koizumi, go a long way in painting the picture of what it was like to work under the cinematic sensei in realizing his magnum opus.

Also included in the supplements is a 50-minute tribute, care of AK’s translator, Catherine Cadou, whose role in his career, as she puts it, was to translate the inexpressible into other cultures. Cadou’s documentary offers a series of endearingly impassioned interviews from disciples like Bernardo Bertolucci, Alejandro G. Iñárritu, Hayao Miyazaki, Martin Scorsese, and more, all of whom can’t help but get teary-eyed when discussing the man of the hour.

But of all the great features crammed within, no document can possibly provide more insight into the production of Dreams than Nobuhiko Obayashi’s epic two-and-a-half-hour featurette, aptly titled, ‘Making of Dreams’. Shot throughout the year 1989 up until wrapping in 1990, the great Obayashi (House, His Motorbike Her Island, Labyrinth of Cinema) acts as the pupil interviewing his master in a rare and satisfyingly lengthy conversation, all the while cross-cutting to his extensive wealth of behind-the-scenes footage, and even better, treating us to interspersed concept illustrations drawn by Kurawasa himself, shown in contrast to the realized sets.

All in all, not only do I consider Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams to be an essential purchase for any Criterion collector, but for those without the necessary equipment, Criterion’s brand new 4K edition provides ample motivation for hi-fi dreamers everywhere to take the leap into the world of UHD.

The film looks and sounds heavenly on my pop-up 200-inch screen, and given that it may take until I’m 80 years old to truly understand the aesthetically open place in which Kurosawa eventually landed (the place in which Scorsece has now fallen suit), I’m grateful that, in the meantime, I have such a perfect method with which to continuously re-experience the culmination of Kurosawa’s lifelong aspirations.