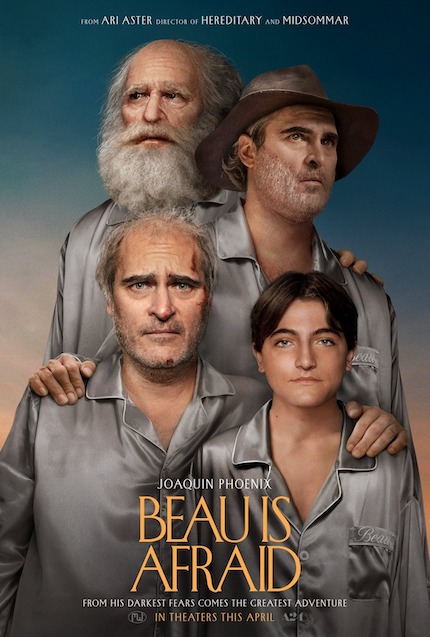

BEAU IS AFRAID Review: Ari Aster Delivers Another Brilliant, Confounding Masterpiece

Joaquin Phoenix stars in the new film by Ari Aster.

After following up one absolute banger, Hereditary, with another, equally absolute banger, Midsommar, writer-director Ari Aster seemed all but poised for an early career stumble.

His third film in five years, Beau is Afraid (formerly Disappointment Blvd.), isn’t. Far from it.

As brilliant, singular, and nerve-shredding as anything in Aster’s earlier films, Beau is Afraid, a surrealistic black comedy, serves as confirmation — as if any confirmation was still needed — that Aster is one of our most talented, creative, risk-embracing filmmakers. And with possibly only contemporary filmmakers Robert Eggers (The Northman, The Lighthouse, The Witch) and Jordan Peele (Nope, Us, Get Out) as equals or rivals of similar talent and vision, Aster seems destined for a long, fruitful career as one of America’s top-tier filmmakers.

Divided into three unnamed chapters and an epilogue, Beau is Afraid opens with the title character, Beau Wassermann (Oscar winner Joaquin Phoenix, delivering another singular, unforgettable turn), at most likely the high point of his ill-fated, perpetually cringe-inducing existence, his birth. In the first sign of many of Beau’s crippling, reactive anxiety, Beau eventually leaves the warm, amniotic comforts of his mother’s womb.

When he does, it’s to the stinging, unqualified disapproval of his mother, Mona (Zoe Lister-Jones in flashbacks, Patti LuPone in the present day). It’s enough to send Beau into a lifetime of therapy -- it does -- and an equally crippling inability to make a single, life-bettering decision that doesn’t involve a withering phone call to the judgmental Mona or a weekly visit to his unknown therapist (Stephen McKinley Henderson).

Using broad, crude strokes, Aster takes a shallow dive into Beau’s life between the aforementioned birthing scene and his present as a sad, pathetic, lonely middle-aged man, graying, balding, and out of shape in big, bold strokes, emphasizing the blurring and eventual erasure of the thin, mutable line between objective and subjective reality. Present-day Beau lives in a nightmare extrapolation of ‘70s New York City. It’s not just rife with crime and criminality, it’s filled with every negative, reactionary projection typical of the conservative mindset: dirty, unclean streets, abandoned corpses, and a zombie-like horde of the dispossessed and the unhoused.

For Beau, getting home from his therapist’s office to his apartment in a dilapidated apartment building qualifies as an ordeal, one filled with the horrors of the modern world. Beau must navigate the attentions of the aforementioned horde, an angry, tattooed man, and a naked knife-wielder.

It’s enough to send the anxiety-ridden Beau into a film long panic attack, but to Aster, a filmmaker with an obvious sado-masochistic streak, an unrelenting desire to play god with his unwitting characters (especially the poor, hapless Beau), and an irresistible urge to work out his mother-related issues (guilt, shame, and so forth) on cinema screens, it’s not enough. It’s only the start.

That start involves Beau inadvertently missing a flight to see his mother (anxiety alert), the curious loss of his luggage and apartment keys (same), and becoming dispossessed himself (also, same) over the course of a terrifyingly event-filled day and evening. Before he can recover from those setbacks, he’s awakening in the seemingly safe home of an upper-middle class couple, Grace (Amy Ryan) and Roger (Nathan Lane), eager to help a literally downtrodden Beau heal physically, if not mentally and emotionally, especially after he learns news of Mona’s premature departure from her mortal coil.

The visit to see his mother adds both a layer of urgency and poignancy. It’s also fueled by a particular strand of all-encompassing Jewish guilt.

That, of course, is just a new beginning, a temporary reset of Beau’s life, and a temporary one at that. Beau’s outwardly inoffensive presence in his newfound family functions as a destabilizing agent, uncovering all manner of unresolved fractures and fissures, each one more potentially dangerous than the last.

It’s not long before Beau, clad first in a hospital gown and later in a pair of monogrammed pajamas, finds himself with another life-altering choice ahead of him. Like the hesitant, passive, reactive central character we’ve encountered so far, though, Beau waits until the last possible nanosecond before deciding on his next course of action.

Both Beau’s twisted, possibly exaggerated city experiences and the disturbing suburban one that immediately follows constitute the first and second chapters of Beau is Afraid. The third, most moving chapter takes Beau to a seemingly magical, forest-dwelling theatre troupe.

They center their itinerant community on staging and performing an interactive play for friends, family, and the odd lost hiker or city dweller. (One man in a bespoke suit repeatedly, plaintively asks: “Why am I here?,” a question that reverberates unanswered throughout Beau is Afraid, specifically the anxiety-ridden title character.)

The play-within-the-film put on by the troupe narratively and thematically echoes the last section of David Lowery’s The Green Knight: a path not taken, a life not lived or, rather, a life lived, filled with incredible highs and devastating lows, triumphs and loss, where Beau, miraculously free of the neuroses and psychoses that have crippled him throughout his disappointment-filled life, steps onto the stage and into an animated world. It’s also the only chapter or section where Beau fully embraces his own agency and doesn’t accept the victimhood status thrust upon him by others.

Nothing, of course, lasts forever and Mona, the primal, inescapable source of Beau’s troubles, looms ever larger as he gets closer to his destination. She’s the archetypal monstrous mother, expecting unconditional love from her only son and giving only conditional love in return.

It’s enough — to paraphrase a long gone, prescient literary magazine, Granta — to f*ck you up irrevocably. Ever the pessimist when it comes to the human condition and family structures (nuclear and otherwise), Aster reaffirms Beau’s inability to escape Mona and what she represents literally, spiritually, or metaphysically.

It’s certainly bleak, even cruel, but anyone familiar with Aster’s previous two films shouldn’t have expected anything different, let alone a conventionally upbeat, uplifting ending. It’s also never less than hilarious, as Aster rains indignities of every shape, size, and color on poor Beau’s unsuspecting head.

By the time the credits roll on Beau is Afraid, Aster has not only re-confirmed his status as a unique voice in contemporary American cinema, he’s also established himself as a chronicler of the disintegration of the modern American family in particular and relationships in general. Families, biological or otherwise, are, in fact, destiny.

Beau Is Afraid is now playing in New York and Los Angeles movie theaters; it expands nationwide on Friday, April 21, via A24 Films.

Beau Is Afraid

Director(s)

- Ari Aster

Writer(s)

- Ari Aster

Cast

- Joaquin Phoenix

- Patti LuPone

- Amy Ryan