Blu-ray Review: Criterion Re-explores THE HUMAN CONDITION

Masaki Kobayashi's epic of inhumanity in and around World War II gets a Blu-ray upgrade.

What’s to be said about The Human Condition? In the case of the epic-length Japanese film of that title made, plenty.

Directed by Masaki Kobayashi (Harikiri) and released in three distinct parts between 1959 to 1961, the whole 579 minutes of The Human Condition is nothing less than an immaculate endurance test of sensibility. It is a beautifully made and sometimes brilliantly compelling endurance test, but an endurance test all the same.

Around the hour-and-twenty-minute mark, I realized that in terms of ordinary running times, I was only the equivalent of fifteen minutes in. I was then warned by a fellow Criterion buff to pace myself — as great of an undertaking as the production is, there’s not a single moment of levity in the whole ten hours. He wasn’t kidding. By the time I reached the three-and-a-half-hour mark and completed Part One, I was asking myself if I was really going to be able to get through this. This much expertly-rendered real-life brutality is a rough go.

It’s not that The Human Condition is in any way a poor film. Quite the opposite, really. It’s simply a very, very heavy film. And justifiably so… Mankind’s inhumanity towards man is never an airy topic, particularly when it’s explored within the framework of World War II-era Chinese labor camps, military mistreatment, and combat fatigue. In such, The Human Condition is also a landmark or World Cinema. Some claim it to be a masterpiece.

Based on the sprawling 1958 novel by Junpei Gomikawa, the typically staid venerable studio Shochiku (best known as home of Ozu’s family-centric dramas) went all in for Kobayashi’s massive vision and desire to maintain as much of the author’s content as possible. At nine hours and thirty-nine minutes, I should say he appears to have succeeded. Never showy but always meticulous in its wartime detail of cramped barracks and mundane settings, The Human Condition is, perhaps deceptively, one of the most expensive Japanese productions of its time.

Every new development brings harrowing physical and psychological abuse. Quite often it’s meted out onto characters we’ve become attached to. Sometimes though, it’s those characters committing the atrocities. The point is clear: war brings out the worst in everyone.

For The Human Condition, Kobayashi teams up with acclaimed visionary cinematographer and dyed-in- the-wool communist Yoshio Miyajima. It must be said that this pairing not only results in some incredibly breathtaking and appropriately harrowing imagery, but their shared ideological wavelength meshes to bring out an assured humanism throughout. Kobayashi and Miyajima would most notably reteam for 1962’s Harakiri and 1964’s Kwaidan.

Also vital in the essential humanism of this saga is leading man Tatsuya Nakadai as Kaji. There is scarcely a scene without Nakadai- good thing the camera absolutely loves him. In his fully committed portrayal of Kaji, the actor is completely resolute. Committed, staunch, but never insensitive, Nakadai’s Kaji is a leading man performance for the ages. Nakadai, in Kaji’s moments both honorable and despicable, is never not compelling.

Kaji begins the story as a capable young man enthusiastic about his opportunity to sidestep Japan’s mandatory military service just as the Second World War is ramping up. In accepting a job as a labor representative for Japan’s imprisoned Chinese workforce, he’s ensuring a future for himself with his devoted wife, Michiko (Michiyo Aratama).

The brutal conditions he finds at the isolated work camp, however, prove to be beyond inhumane. As the suffering Chinese prisoners are regularly beaten and pushed to levels of near death, Kaji sooner than not finds his learned patriotism for Imperial Japan at odds with his brewing sense of humanistic outrage. His compassion on behalf of the Chinese only causes tensions to escalate within the camp, resulting in executions with a samurai sword. (Through the whole of The Human Condition, Kobayashi makes repeated points of critically considering and subtly examining Japan’s myth of the noble Samurai). It is Kaji’s inner torment giving way to intensified atrocities that drive the first of the three separate films, No Greater Love.

The second film (each is subsequently broken into two parts), The Road to Eternity, finds Kaji betrayed by the system and forced to serve in the military after all. It is with full confidence that Kobayashi continues his unflinching critique Japan’s past atrocious practices and their abysmal effect on the common people. In this middle entry, Kaji must endure basic training, an arduous and soul-crushing ordeal for all recruits. His reputation as a “red” sympathizer follows him from the labor camp, but so does a certain clout, ensuring him a higher rank and authority once he moves into regular service. In this arduous process Kaji is privy to a situation wherein a weaker private is exploited and ground down by an abusive superior, not at all unlike Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. Clearly, that film was inspired by this one.

Film three, A Soldier's Prayer, opens in the aftermath of a costly and viscous battle. Kaji, at this point the leader of a mostly annihilated platoon, has officially found himself exactly where he was trying to avoid when he took the doomed labor representative job at the beginning of No Greater Love. Abandoned and alone, Kaji denounces the war, the army, all of it. He’s heading home. Word is that the war is probably ending, anyhow.

The journey at follows, however, is no less a horrendous experience than what’s come before. Kaji, hyper-focused on reuniting with his beloved Michiko, finds himself an unlikely Ulysses on a grueling odyssey wrought with death and exhaustion before eventual capture and torture by the Soviet army. Here, Kaji not only finds himself on the opposite side of the situation in which he began The Human Condition, but he is also confronted with the reality that even communism (supposedly so different from the ideology he’s been raised on) is not without gross oppression.

Yet, as famously long as the whole of The Human Condition is, it is never slow or methodical. Every single scene is brisk and tightly cut, leaving no trace of narrative fat or what some may consider pretentious lingering. The Human Condition, in its unending litany of one damned thing after another, never stops moving forward to its inevitable conclusion.

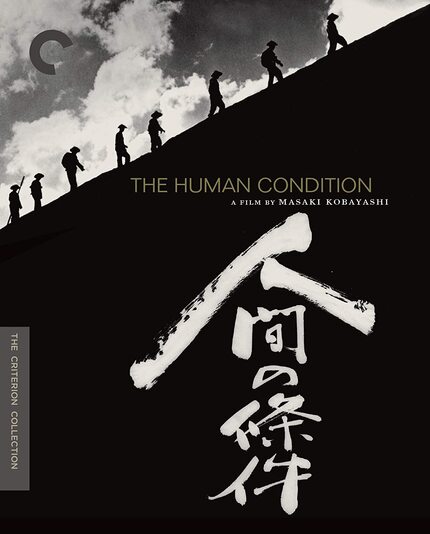

In terms of cover art and bonus features, Criterion’s Blu-ray release of The Human Condition is basically an as-is port of the company’s previous 2009 DVD release. The whole film and the bonus features are spread across three discs, each tidily containing one of the three individual releases. The packaging is now a thinner clamshell rather than a cardboard box set. The handful of bonus features from back then (two 2009 exclusive interviews and a 1993 TV interview segment with Kobayashi) are represented here, making the jump to high definition alongside the movie proper. Kobayashi and Miyajima’s straightforward but haunting black and white widescreen compositions take on a particularly resonant strength and clarity in 1080p. As in the original presentation, all non-Japanese dialogue is burned into right side of the frame in Japanese. The Blu-ray defaults to English subtitles.

Here are the official bulletpoints as far as the Blu-ray’s details:

• On the Blu-ray: High-definition digital restoration, with uncompressed monaural (Parts 1–4) and 4.0 surround DTS-HD Master Audio (Parts 5 and 6) soundtracks

• Excerpt from a 1993 Directors Guild of Japan interview with director Masaki Kobayashi, conducted by filmmaker Masahiro Shinoda

• Interview from 2009 with actor Tatsuya Nakadai

• Appreciation of Kobayashi and The Human Condition from 2009 featuring Shinoda

• Trailers

• PLUS: An essay by critic Philip Kemp

*****

The Human Condition should be of particular interest to students of Japanese history, World War II buffs, and fans of mid-twentieth century Japanese cinema. Criterion’s initial release of Kobayashi’s epic of unrelenting miserabilism turned plenty of heads in 2009. This Blu-ray upgrade is less likely to do so, if only for the fact that it offers nothing new outside of its 1080p upgrade. That presentation, however, is a significant factor in its own right. Just as Kobayashi’s complete film does not let up, nor does the exquisite presentation of Criterion’s Blu-ray edition.

The Human Condition III: A Soldier's Prayer

Director(s)

- Masaki Kobayashi

Writer(s)

- Zenzô Matsuyama (screenplay)

- Kôichi Inagaki (screenplay)

- Masaki Kobayashi (screenplay)

- Jumpei Gomikawa (novel)

Cast

- Tatsuya Nakadai

- Michiyo Aratama

- Tamao Nakamura

- Yûsuke Kawazu