Review: YELLOW ROSE Blooms in Times of Trouble

Diane Paragas' debut feature, with a revelatory central performance by Broadway star Eva Noblezada, offers a unique, finely crafted, and timely take on the issues of immigration and undocumented people.

Over 15 years in development, Diane Paragas' debut feature Yellow Rose is timely in ways equally fortuitous and unfortunate, arriving as it does at a time of heightened emotion and political rhetoric around the issues surrounding undocumented immigrants in the U.S.

Usually, these issues involve people coming from Mexico and other Central and Latin American countries. But what’s often hidden and underreported is that many people from Asian countries are impacted by these issues and suffer the same consequences from the hostile and dangerous political and social climate accompanying them.

Yellow Rose vividly and affectingly dramatizes these issues with a nuanced and smartly written screenplay (by Paragas and Annie J. Howell) that’s refreshingly free of cliché and syrupy melodrama. How this film deftly avoids feeling over-familiar is largely due to its specificity of detail concerning its milieu, which is the Austin, Texas country music scene.

The central character is Rose Garcia (Eva Noblezada), a 17 year-old Filipina who lives with her single mom Priscilla (Princess Punzalan) at a roadside motel on the outskirts of Austin where her mom lives and works cleaning rooms. Rose's mother is undocumented, as is Rose herself, but she doesn’t learn that fact until later.

Despite the looming threat of discovery by the authorities, Rose lives more or less the normal sort of life of young women her age. Her single, overwhelming passion is for country music, having been a fan of this music since she was little. She plays her guitar and pens very personal songs, the subject matter often revealing how out of place she feels where she lives; in one song, she describes herself as a “square peg” in a “round hole,” combining the universal feeling many teenagers have of being something of a misfit amongst their peers with her personal status as being part of a racial minority.

Rose is very shy about her songwriting, not performing these songs in public, only playing them to herself in her room. However, her solitary music practicing does gain the attention of one person: her classmate Elliot (Liam Booth), who works at the guitar store where Rose buys her strings.

There seems to be some sort of potential budding romance, though initially it seems that such interest is almost entirely on his end. Nevertheless, he manages to coax a bit of singing out of her on a car ride, and even gets her to sneak out with him on an trip to a honky-tonk club in downtown Austin (with the cover story of a church outing to assuage Rose’s mother).

It’s when they get back home from the club that the narrative takes a dark turn, when they discover that ICE has raided the hotel where Rose and her mother live, and they watch in horror as Rose’s mother is taken into custody by the authorities. Rose now knows she’s undocumented as well, and subject to the same danger of deportation. With Elliot’s help, Rose goes on the run, seeking shelter at the home of her aunt Gail (Broadway icon Lea Salonga). Unfortunately, this doesn’t work out so well, mostly due to the opposition of Gail’s husband to taking Rose in.

Eventually, Rose finds her way back to the club she went to with Elliot, called the Broken Spoke. The kindly club owner, a woman named Jolene (Libby Villari) – a nod, perhaps, to the famous Dolly Parton tune – takes a liking to Rose, having remembered her from Rose’s first visit. Jolene takes Rose in and gives her a job at the club, and a room upstairs.

Rose is also reintroduced to country musician Dale Watson (playing a fictionalized version of himself), who was performing at the club when Rose was first there. Dale becomes an informal musical mentor, as well as a bit of a father figure.

These somewhat happier days for Rose are contrasted with the nightmarish experiences of Rose’s mother in ICE custody, as she’s stripped of her identity and only known by an inmate number, and is often treated harshly by the guards. Rose, again with Elliot’s help, manages to find the place where her mother is being held, and has brief but very emotional phone calls with her mother, and is eventually able to visit her in person, but again, only briefly.

Rose and Elliot confer with immigration lawyers, who are sympathetic and helpful, but are unable to do much to improve the situation for Rose’s mother or come up with a way that she can stay in the U.S. And Rose herself is far from out of the woods, with the threat of being deported herself still looming on the horizon.

Diane Paragas has created a music-filled (with songs penned by Paragas, Watson, and others), lively, and heartfelt film that’s graced with a wonderful, often revelatory turn by Eva Noblezada, an immensely talented Broadway star (Miss Saigon, Hadestown) making her feature film debut. Her acting and musical chops are equally impressive, and she delivers a winsome, yet quietly powerful performance and screen presence that all by itself elevates the film.

Noblezada’s undeniable talents are matched note for note by the un-showy yet marvelously accomplished work by Paragas and her crew behind the camera. The contributions by cinematographer August Thurmer and production designer George Morrow are key, assisting Paragas in lending her depiction of Austin and its environs both soaring lyricism and down-to-earth realism.

The film’s depiction of its Texas setting is admirably absent of hackneyed, lazy stereotypes of backward, racist Southerners. Though of course such folks exist (Rose reveals late in the film that her childhood nickname “Yellow Rose” was basically an ethnic slur), the film gives itself great credit by not grabbing the low-hanging story fruit of Eva facing cartoonishly drawn racist antagonists. Even though Rose’s Filipina heritage makes her an anomaly in the country music world, she’s seemingly embraced and accepted by everyone around her. (Granted, the film largely takes place in Austin, perhaps the bluest area of Texas.)

Yellow Rose, despite its politically fraught subject matter, is by no means a depressing or despairing work. To the contrary, it finds room for humor and moments of lightheartedness, and finds a rich, remarkable balance between the light and the dark in the lives of its characters in a compelling and beautifully crafted fashion. The film’s final frame finds Rose defiantly staring down the camera after she delivers her big-break musical performance at the Broken Spoke. Rose lets us know that despite the social and political obstacles she must confront, she’s here to stay, and she’s not going anywhere.

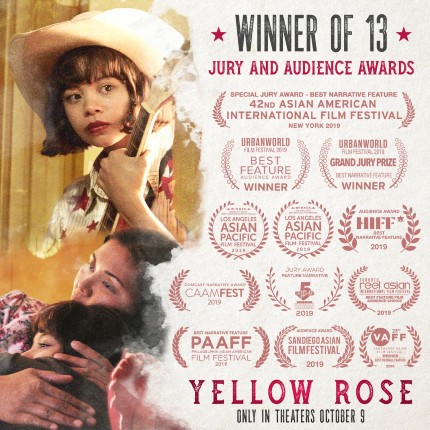

Review originally published when the film at the Asian American International Film Festival in August 2019. Yellow Rose will open in select U.S. theaters on Friday, October 9, 2020. For more information, visit the film’s official site.