Review: SERVANTS, Visually Captivating Artful Period Film About Persecution

The new artistic director of Berlinale, Carlo Chatrian, set up a new competitive sidebar, Encounters, at this year's edition for bold filmmakers with a unique vision and innovative approach to cinematic language. A long-awaited sophomore fiction feature from a Slovakian producer and director, Ivan Ostrochovský, got picked up for the inaugural selection of the new programming section.

Ostrochovský, a documentary producer and director by trade, swerved to fiction filmmaking with a feature-length fiction debut Koza, a semi-biopic docu-fiction where the lead portrays a version of himself. Koza received laurels traveling the international circuit and Ostrochovský suddenly appeared in the spotlight on his new career trajectory prompting high expectations.

Five years in the making, Servants certainly do not lower the bar. On the contrary, the black and white drama, co-produced by Slovakia, Romania, Ireland and the Czech Republic, relieves itself from the shackles of domestic conventions.

While Koza emphasized the Eastern European place of origin also by virtue of the story, Servants have the sophisticated structure and aesthetics possessing all the necessary predispositions for a global arthouse film beyond the former Iron curtain similarly to the success of for example Polish drama Ida.

The story of Servants is set into the times of the Communist rule of the early 1980s in Czechoslovakia. Two high-school friends Juraj and Michal enter a seminary, a not so obvious career choice in socialist regime swarming with secret agents ready to repress any deviation from the official ideology. However, they both soon find out that seminary won´t shield them from the regime as the specter of Communism looms wide in the halls full of priests and future clerics.

Ostrochovský along co-writers Marek Leščák and Rebecca Lenkiewicz (the writer of Ida fame) settle the struggle of young idealists against the backdrop of true events. The veil of illusion regarding the freedom in the last refuge against the regime in the seminary crumbles down as priests are allowed to carry on their clerical duties only if they refrain from commenting and disputing political and civic life.

The tenets of communism have been already thoroughly clasped over seminary as the regime has been undermining the church from within through state-sponsored religious organization Pacem im Terris (a real-life organization operating from 1971 until the Velvet Revolution).

The protagonists are confronted with the limitations of how to act and what to say and think. While one of the friends mostly keeps up the shape his superiors advise him, the other soon joins the resistance in an underground church operating in secrecy as it did in the early days of the Christian Church under the Roman Empire. The constant tension within the halls of seminary mirrors on the relationship of childhood friends, idealism clashing with conformity and the regime taking the psychical and physical toll.

The dramas (and occasionally comedies) of unsung heroes that rebelled against the Communist regime or worked to erode it frequently at the highest price form a separate canon in the Czech and Slovak cinema. However, Ostrochovský avoids the contraptions and conventions of mainstream storytelling. The director adopts the narrative strategy of detached observer following the fates of two protagonists and how they face grappled with the unfolding the situation.

The write-director consciously eludes the straightforward and one-dimensional portrayal of "the good ones" and "the bad ones". Therefore, he foregoes unnecessary simplification of life under the regime, as some films tend to do heavily influenced by the effects of nostalgia, while evading straightforward moralizing. In the director´s own words, he wanted to depict how easy is to appear on the wrong side of history.

The major assets and change-makers of Servants compared to other similarly tuned period dramas of a character pitted against a system is the combination of elliptical narration and starkly artful cinematography in a 4:3 ratio along stage setting. Besides being a prolific producer (Domestique or Nina), Ostrochovský is a docu-maker by vocation. His documentary sensibilities shaped the first fiction feature Koza, most notably the raw cinematography, on-location shooting and working with non-professional actors led by the protagonist on whose life the film is based on.

Even though Koza combines different quasi-genre aspects lifted from road movie, social realism drama, even sports film, the final film did not allude to those conventions explicitly by virtue of the film´s formalism and narrative style.

Elliptical narration and even elliptical composition (in case of sports drama, Ostrochovský never puts the focus on a boxing match or the action, shooting instead seemingly irrelevant details) makes the distinction between Koza and other films, whether those should be social dramas, sports dramas or other arthouse fares.

Koza is in the category of its own as Ostrochovský extricates storytelling from the conventional framework redesigning the story´s narrative and prioritizing odd angles and perspectives (the insertion of eccentric coach portrayed by Ján Franek as supposedly misplaced comic relief).

The director preserves the elliptical narrative design however he changes drastically the approach to composition and cinematography with highly photographic sensibilities for space and meaning contained within it, a major transition in formalistic and aesthetic terms.

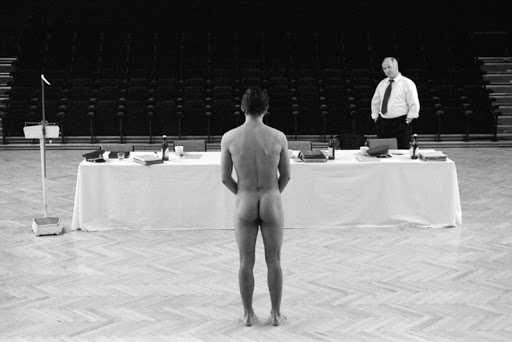

The black and white visuals nourish the noirish atmosphere with most of the scenes set between the four walls of the seminary and create a claustrophobic climate which works as a palpable metaphor for the oppressive system closing in on the dissenting clerics. Meticulous approach to picking up locations, art production (led by the director himself who took up the responsibilities of stage designer) and mise-en-scène result in outstanding imagery eclipsing the actual narrative of dialogue-based scenes.

While Ostrochovský did not shun from the inheritance of documentary filmmaking, mostly in terms of researching the topic and meeting with people who lived through the story of the film´s protagonists, he fully embraces the visual possibilities of the medium. The visual storytelling takes over the verbal narration.

The director retorts to a rather theatrical staging in terms of photography which results into the creation of a film consisting of a series of potent and captivating tableaux. The elliptical approach applies to the cinematography as well resulting into scenes more visually strange, otherworld and surreal than the actual story revolving around clerics oppressed by the state regime would suggest.

The same way Koza defied the codes and customs of genres the film may have been associated with, Servants outdare the bracket of a period film as the cinematography does not conform to the established stylistic approach of historic films.

The film enjoyed its world premiere at the Berlinale.