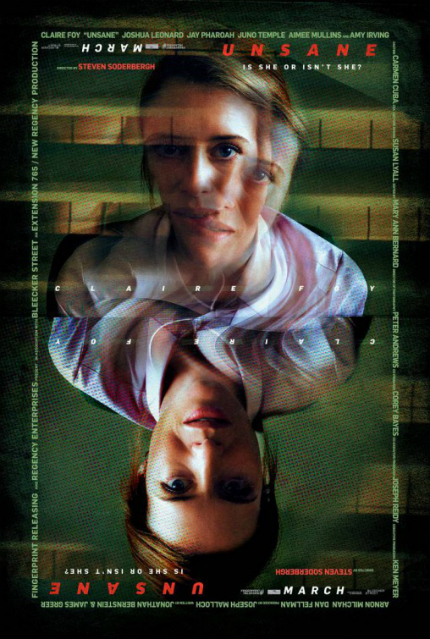

Berlinale 2018 Review: UNSANE, A Stellar Piece of Psycho Fiction

Claire Foy stars in Steven Soderbergh's new, uneasy psychological thriller.

Depending on what your thoughts on Logan Lucky were, it was possible to worry that Steven Soderbergh had hit a bit of a bump in the road last year, but fortunately the director of prized titles like Ocean's Eleven, Magic Mike and Erin Brockovich returns in fine form with 68th Berlinale Main Competition entry Unsane.

Starring The Crown's excellent Claire Foy as the most unusually named Sawyer Valentini, Unsane proves to be an utterly fascinating exploration of sanity that well and truly gets you asking questions. Also shot entirely on an iPhone, the restlessly creative Soderbergh definitely manages to push the boat out cinematically too.

But whatever you do, do not let this movie's underbaked marketing efforts to dress this film up as an easy-selling horror disappoint you. Unsane isn't a horror at all, it's a psychological thriller of the highest order, and should be respected and enjoyed as just that.

Initially, however, it's almost as though this movie opens rather poetically. Somehow (God knows how) Soderbergh draws a striking blue, low light image of a wood at dusk from his Smartphone camera, and Joshua Leonard coos in voice over something about being entranced by a woman in blue from the first time he saw her.

From this eerie, yet romantic opening scene, we slam into an unremarkable office, where Sawyer works in a new job vetting loan applications at a Boston-based bank. Think Mad Men, think oppressive lighting, think everyone confined into their own cramped office cubicle. Here we meet Sawyer officially, as a ballsy woman who isn't afraid to throw her weight around professionally, and is razor sharp in avoiding her manager's inappropriate advances.

Amidst these tense dynamics, the camera behaves in a rather fascinating way. Whilst not necessarily new as a technique, it films from down low when a character is being imposing, and from up high when they are feeling overwhelmed or threatened. At other moments, the camera films dead on, almost as if through a fish eye lens. In the highly compact settings (that have almost no middle ground) and with such a versatile camera, even figures as slight as Foy manage to loom across the screen in menacing and daunting ways.

The whole texture of Unsane is an uneasy, claustrophobic one, and as we see a seemingly friendless Sawyer strike up a one-night stand with absolute cut-throat directness after work, we begin to suspect she has some kind of background condition. Our suspicions only intensify when she then freaks out on the date, and subsequently travels to a clinic to seek counselling for being stalked.

This is a phase in which Unsane most skillfully goads our thoughts. Is Sawyer on the meglomaniac scale given the way we see her behaving with those around her? Is she simply manipulating situations for attention? Is she (and the film itself) hiding a secret which may see her collapse into genuine madness altogether? These are questions which Foy's brilliantly ambiguous and well-judged acting allows us to ask, and it leads us to feel impressively involved when we suddenly find our seemingly relatively sane protagonist being committed to a psychiatric ward.

This in turn ignites one of the core topics of Unsane. As we dance between thinking she is sane and potentially in need of serious medical help, the spectrum of what exactly is mentally healthy seems to expand massively before us. Not only are we driven to question the boundaries of this spectrum, we are also compelled to recognise certain aspects of her behaviour and personality in ourselves.

Onto this concept, however, Soderbergh then brutally hammers two very socially critical nails. The first part of this crucification of American culture lies in the fact that, if Sawyer is sane, is the clinic she's staying at just holding her to profit from her medical insurance? And in the midst of the dismantling of Obamacare, this certainly feels like a potentially very scathing look at what it means to provide medical care for people in America today.

The second hammer blow falls deeply into the wounds of the Weinstein scandal, as Soderbergh sets about exploring whether Sawyer's claims of stalking and male transgressions is really all that crazy. Whilst this soon becomes the main focal point of the film's super charged, electrifying psycho narrative, I do think the dramatic tension between both these questions isn't quite held for long enough in Unsane.

We are soon given fairly indisputable answers to both of these questions, and whilst this is definitely where the heart of this movie lies - I just think that a little bit more doubt on the part of the viewer would have gone a long way. But even once things become clearer, we're definitely still taken on a dizzying cinematic ride into the world of genuine and compelling psychopathy.

Along the course of this journey, moments of fear, desperation and violence by a fiercely physical Foy become incredibly visceral in Unsane. Soderberg drags you kicking and screaming round a dark, neglected, 70s-looking mental health clinic, with lots of cool filmmaking tricks along the way. In fact, there's one particularly neck-breaking scene that I think actually had me bolting out of my seat. Plus, Joshua Leonard's acquiline, beardy face and his large, retro glasses make him the perfect suspect to potentially hate.

Ultimately, Unsane adds up to a very thought provoking look at male-female relationships. But the movie is also a remarkably uncomfortable look at where the line exists between sane and insane. It equally makes you question at what point people do or don't become a threat to themselves and others, and what makes them become dangerous in the first place.

P.S. If you like this film's exploration of sanity, please also put Josephine Decker's Madeline's Madeline on your radar. It's a very different movie, but if that film's not up for an Academy Award this time next year, tables deserve to get flipped.