70s Rewind: EMPEROR OF THE NORTH, How to Ride the Rails

Those eyes; those teeth!

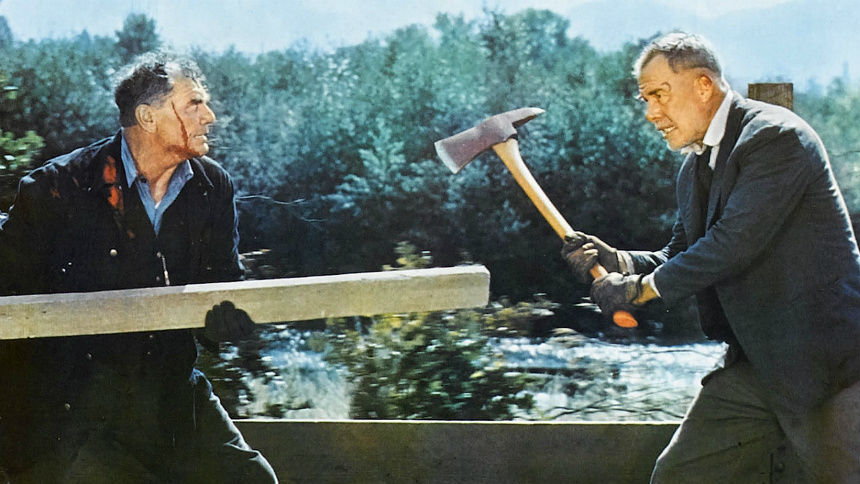

When Ernest Borgnine's face fills the screen in Robert Aldrich's Emperor of the North, it's a terrifying sight. Shack, the character Borgnine embodies, is a conductor on a freight train in the Pacific Northwest in the U.S., and as the brief opening sequence of the film makes frightfully clear, he will stop at nothing to keep hobos from riding his train for free.

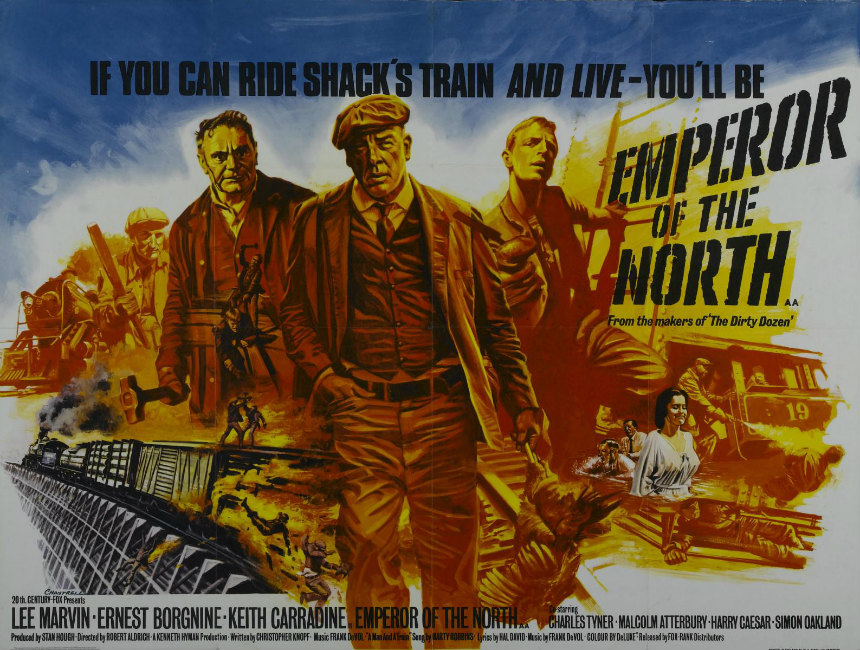

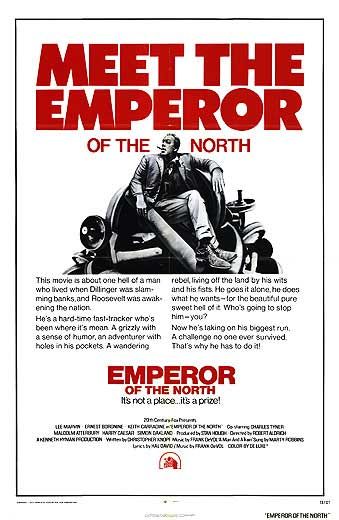

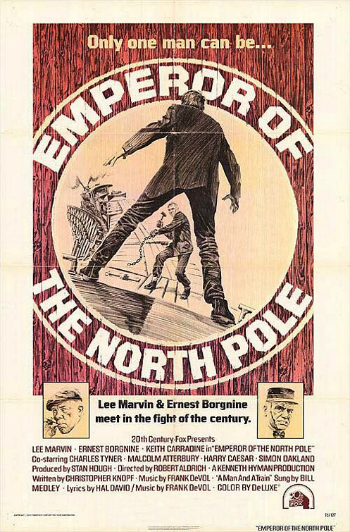

Set in October 1933, the film -- released in 2015 by Twilight Time in a limited edition that is still available on a gloriously beautiful Blu-ray as of this writing -- speaks to the call of the wild, the glory of the open road, and the romanticism of freedom from all possessions and responsibilities. Originally released theatrically in 1973 (first as The Emperor of the North Pole before the title was shortened and the film re-released), it is also a heedlessly nostalgic picture, not unlike other films of its era, such as Peter Bogdanovich's Paper Moon.

Unlike Bogdanovich, however, Robert Aldrich was not a young man; he turned 55 in the year of this film's release. Some 10 years before, he had resurrected his career by directing Joan Crawford and Bette Davis in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? and then tried to repeat that success with Hush...Hush, Sweet Charlotte, as dramatized in the FX limited series Feud. He was recognized as a great director -- see Alain Silver's marvelous, thoroughly researched career consideration at Senses of Cinema -- and enjoyed popular acclaim with films such as The Dirty Dozen in 1967.

But with the subsequent emergence of younger, fresher voices in Hollywood, like Bogdanovich, William Friedkin, Martin Scorsese, Brian DePalma, and Francis Ford Coppola, it's no wonder that an experienced, greying studio hand like Aldrich was pushed back. After all, it had been about two decades since Aldrich made snazzy, dynamic pictures like Kiss Me Deadly and The Big Knife.

But with the subsequent emergence of younger, fresher voices in Hollywood, like Bogdanovich, William Friedkin, Martin Scorsese, Brian DePalma, and Francis Ford Coppola, it's no wonder that an experienced, greying studio hand like Aldrich was pushed back. After all, it had been about two decades since Aldrich made snazzy, dynamic pictures like Kiss Me Deadly and The Big Knife.

Aldrich never lost his gift for staging dramatic and engaging action sequences, though, and that's fully evident in Emperor of the North. It's based on an original screenplay by Christopher Knopf, who was himself in his early 40s at the time; he had broken into feature films in the late 1950s -- including 20 Million Miles to Earth, the Ray Harryhausen vehicle -- and then wrote extensively for television from that period until the 1990s.

Borgnine and the top-billed Lee Marvin had both worked with Aldrich in the past. This was Borgnine's fifth collaboration with the director, beginning with Vera Cruz in 1954. (They would work together once more in 1975's Hustle), while Marvin first worked with Aldrich on 1956's Attack!. Both actors appeared in John Sturges' Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), as well as in Aldrich's The Dirty Dozen.

Aldrich, Borgnine (age 55 during filming), and Marvin (the youngest of the three, just 48), could all relate, no doubt, to the idea of a still vital older generation stubbornly holding on to their respective perches, despite the invasion of a horde of young people who wanted to knock them off. Borgnine and Marvin both won Academy Awards for Best Actor (in 1955's Marty and 1965's Cat Ballou, respectively), but leading roles such as these never came their way again in the years that followed. Borgnine kept busy until his death at age 95 in 2012, always giving more than required in his supporting performances. Marvin also kept acting until he was fully extinguished at age 63 in 1987; as much as I enjoyed him in Death Hunt (1981), he was, sadly, in decline.

Neither Borgnine nor Marvin could have known the future, of course, and, in the moment of filming, Emperor of the North might have seemed like just another picture, and so they spent July 11 through October 5, 1972 filming on location in Oregon and also at the Fox studio lot in Century City, California.

The film is rambunctious, wild-spirited, and very, very masculine; only a couple of women even get lines of dialogue. It's very much a white man's world, a place where a man of color is employed to shovel coal into the steam engine and a few of the many hobos are played by actors of color.

The film is rambunctious, wild-spirited, and very, very masculine; only a couple of women even get lines of dialogue. It's very much a white man's world, a place where a man of color is employed to shovel coal into the steam engine and a few of the many hobos are played by actors of color.

Otherwise, old white men rule the established order of things. Shack (Borgnine) is the conductor of the No. 19 freight train, ruling over his crew -- engineer Hogger (the final feature film appearance by Malcolm Atterbury, whose father, in real life, was president of the Pennsylvania Railroad), fireman Coaly (Harry Caesar), and brakeman Cracker (Charles Tyner) -- with ruthless intensity. Often, he doesn't need to speak; he just glowers or grimaces, and things get done.

A No. 1 (Marvin) is not given to a lot of gab, either. He is a solitary traveler with a mysterious past. We don't know anything about Shack's past, either, but at least he has a job to do. Evidently, A No. 1 has been riding the rails for years; he later makes reference to making a career out of being a hobo and boasts that he's been the rare type who's been able to do so. It's not certain when, exactly, hobos began riding the rails, though it appears to have begun in the late 19th century, with one count putting the number at some 700,000 in 1911, increasing greatly during the Depression Era in the 1930s.

How long has A No. 1 been riding the rails, then? For 10, 20, 30 years? Was he born into poverty and embrace a life of mobility, rather than acquisition? Has he ever had ties to anyone else? Small hints and suggestions leak out as he ends up traveling in the company of Cigaret (Keith Carradine), as a feckless, boasting youth calls himself. Unlike Shack, who has lost whatever empathy he once may have possessed, Shack manifests a degree of fellow feeling toward those he encounters and eventually he begins to feel sorry for the feckless kid.

Having recently soaked in Carradine's carefully measured and masterfully refined role on FX's Fargo, it's a pleasure to revisit him in his youth, when he was defining his own, distinctive screen personality in the shadow of his father John Carradine and his older half-brother David Carradine, who was, nonetheless, instrumental in helping him become an actor. Turning age 23 during production on his second feature, he is certainly the picture of callow youth. Yet he also displays sufficient presence to stand notably and strongly against Marvin and Borgnine. He offers a slice of the "modern generation" that is not very complimentary toward young people in the 1970s. (Later, the actor won an Academy Award for Best Song -- "I'm Easy" -- in Robert Altman's Nashville (1975).)

Really, the film feels like a salute by the older generation to to the older generation, as well as a salty farewell. Shack and A No. 1 may be older gentlemen, but they're not ready for the retirement home. It's as though screenwriter Knopf, director Aldrich, and actors Marvin and Borgman were standing up, shaking their fists, and yelling 'We're not dead yet!'

As I mentioned earlier, Emperor of the North is currently available from Twilight Time on Blu-ray. This 2015 edition includes an isolated score track, featuring music by composer Frank DeVol, who collaborated with Aldrich on his first score, 1954's World for Ransom, and frequently thereafter, right up to Aldrich's final film, ...All the Marbles (1981).

The disc also includes two TV spots, the original theatrical trailer, and an audio commentary by film historian Dana Polan, who approaches the film from a very informed, very decisive, very knowledgeable, very intelligent academic perspective, if that's your thing.

Julie Kirgo wrote the program notes, which point to Twilight Time's Nick Redmon, who says screenwriter Knopf drew inspiration from two memoirs by Jack London, and also notes that Sam Peckinpah rewrote the script and tried to direct the project for several years before dropping out.

I've written about the film for this site in the past, first in 2006 and again in 2011; it remains one of my personal favorites.

70s Rewind is a column in which the writer revisits his favorite film decade.