Interview: Everardo González On His Powerful Documentary DEVIL'S FREEDOM

Everardo González, documentary filmmaker best known for Ladrones viejos and Drought (Cuates de Australia), is visibly enraged when he starts talking about the case of Javier Duarte, a Mexican politician who in early 2017 was detained for a huge corruption case.

We all know the man is absolute dirt and yet the first hearing quickly reminded us that Mexico is the land of impunity. That’s why González is angry, though the very idea that Duarte might beat justice is hardly a surprise in the Narco-state that is our country.

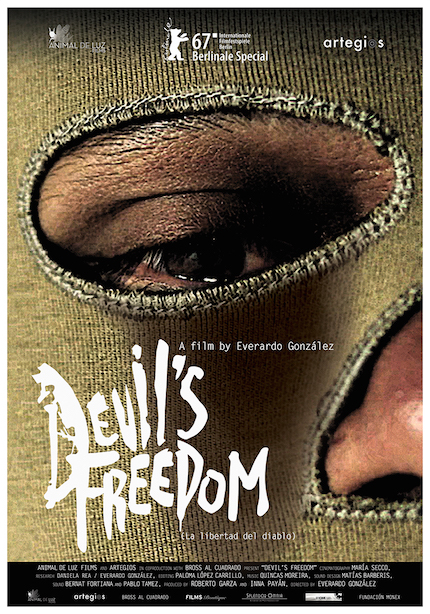

Everardo’s latest documentary, Devil’s Freedom (La libertad del diablo), tackles the consequences of the Mexican Drug War from the personal perspective of several individuals. There are testimonies of victims who lost their familiars or have been kidnapped and tortured, offenders who pulled the trigger for money, policemen who have decided to do justice by their own hand due the impunity, and soldiers who followed orders from organized crime.

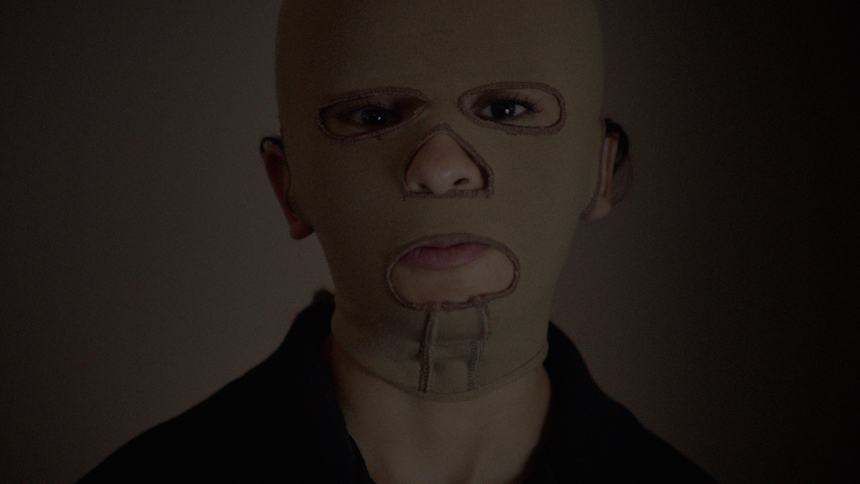

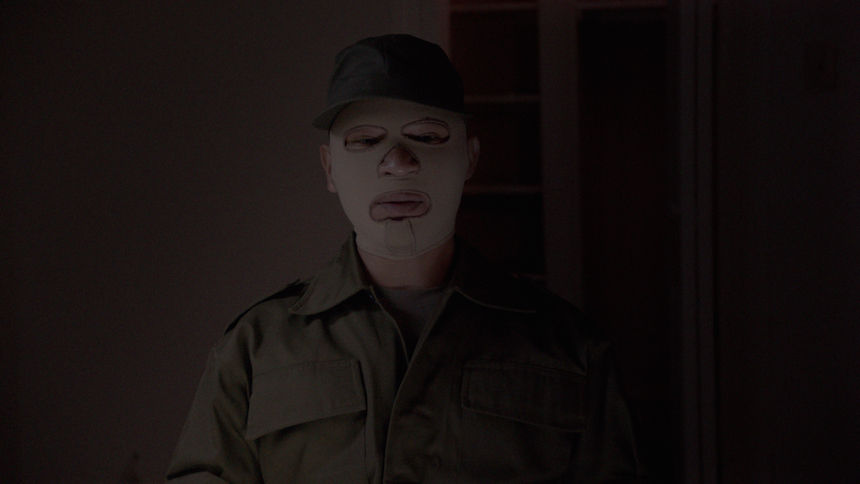

The film is minimalist, as González only shows us the faces of the interviewees covered by a mask, while each shares their reality. There’s no need for more in order to achieve one of the most brutal and powerful Mexican films in recent memory.

Since Devil's Freedom is now playing in Mexico City – as part of Cineteca Nacional’s 37 Foro Internacional - I sat down with Everardo González for the following conversation.

ScreenAnarchy: A couple of months ago I interviewed filmmaker Tatiana Huezo about her documentary TEMPESTAD, just days after the murder of journalist Javier Valdez. She told me her interest in making a film on the drug war and the impunity began when this complex problem practically knocked at her door. In your case, what was the main motivation behind DEVIL’S FREEDOM?

Everardo González: I don’t know what to say. Javier Valdez contributed to this film, but everything is behind now. I don’t think that’s relevant, to compare myself with a victim would be even immoral. I think my job is in some way related to yours, to the people that make narrative journalism, and I think that’s the value of the documentary - beyond its aesthetic, its legitimation in foreign countries, its recognition with the critics and the film unions -, that it leaves a testimony of the times.

We all have a direct bond with the organized crime in one way or another, from the side of the victims or the offenders. We all have some story connected with violence and the idea of living with fear. Though it’s not an obligation that you leave a testimony of this only if bloodshed happened on your side.

The reason why I made this film was related to a moral obligation I had with the documentary. During Felipe Calderón’s term as president, I wondered what kind of movie I could make to capture what was happening, but I felt that a lot was going on and there was little room for reflection. Since the movie was not based on a case in particular, it was more of a philosophical project.

What really detonated the film was when the media began referring to the killings of civilians as collateral damage. A book written by a friend was a motivation as well: Fuego cruzado by Marcela Turati, which is a testimony of the people involved with the theme of death that questioned the media’s way to handle it, just before the pact signed to stop generating news about the organized crime under the argument that the media was turning into the cartels’ spokesperson.

The project started a long time ago but it took a different direction once I filmed El Paso, a documentary that began with the exile of a friend who was the correspondent for the El Norte newspaper in Ciudad Juárez, right when it was announced the Operativo Conjunto Chihuahua.

It was also important the relationship I had for many years with the police source and the connection I have now with people who cover violence, like Marcela Turati, Diego Enrique Osorio, Daniela Rea and Manuel Almazán, all who became part of the media right when the country became what it is now: a common grave.

The conversations with friends, the close people that were murdered, the relationship I have with the Mexicanos en el Exilio organization, talking with people who are in hiding with fear, and the idea that a documentary is relevant for the future and not necessarily for today. That’s why I made this movie.

Other recent documentaries on the drug war explore particular cases, like NARCO CULTURA and its two main characters, or CARTEL LAND, which is about the autodefensas movement. In that sense, how complicated it was to propose a different type of documentary, told from several individual perspectives?

When I started making documentaries I didn’t have the need for reflection, the notion of not depending on the circumstances to make a movie, or the interest in concepts like empathy and the truth. I’m not sure I would have been able to make this film when I started. The producers really only trusted me based on my previous work. But it wasn’t easy. The project went down a couple of times, even before I made El Paso, in fact two stories in El Paso were extracted for this project.

This kind of work is always interesting for me; in fiction I think in something like THE WIRE…

I love The Wire, it’s my favorite TV series, for sure.

It exposes all the sides and it doesn’t give you easy answers. When did you decide that DEVIL’S FREEDOM needed to be told not just from the perspective of one person? We see the victims, the criminals, the soldiers…

I didn’t want to make a film with only one responsible. The social chorus always shouts at the State, but that’s like asking God for rain, it’s an abstraction, the State is many things but it’s also us. So I wanted that the frontier between a victim and an offender faded away. In an extreme situation, we all are capable of committing atrocities.

One case only wouldn’t have worked became I was experimenting with the idea of empathy. It’s practically impossible not to empathize with the victims; I wanted to explore the possibilities of empathizing with those that commit direct atrocities. It’s a complex risk, going across ethical limits, but I didn’t want to make a simple movie.

The victim is always welcomed by the society, but that’s not the case for the offender, though we live in a society that praises and idealizes the criminal. That exposes the double standards of the Mexican, perfectly capitalized by the producers of the narco series.

For me it was important to have a chorus to say to the viewer that we are also direct responsible for what’s going on; either because we ignore it, keep voting for the criminal, lack the capacity for organization, or feel indifferent.

One or two stories wouldn’t have allowed me to do that, because the film is not based on the anecdote but on reflection. It’s maybe closer to an essay than to a narrative movie because it doesn’t rely on character or plot, rather on concepts like fear, obedience, vengeance and forgiveness.

There’s a testimony of a man that was tortured by the police; he says that it’s the very first time he shares the story with someone. How is the process to manage this atmosphere of trust?

The relevant thing is that they feel there’s a genuine interest. I allow them to have moments of silence, for reflection or memory. When they break the silence, complex stuff is coming, because there’s introspection.

The presence of the mask allowed a lot of freedom; the mask was not really an element for anonymity, rather a possibility of having a testimony closer to the truth. There was a mirror and a dark curtain, and who was in front of the camera had the sensation of being alone in front of a mirror.

The process of introspection allowed us, as spectators, to see maybe the very first moment of reflection for many of them, not only of this man that had been incapable of talking about torture and harassment, but also of the guy that reflects on what it meant for him to murder a child. That was one of the questions I had, if they we aware of the damage they were provoking.

It also allowed to have valuable and powerful testimonies to understand this society, like the one of the girl who can think of herself as a torturer due the need for vengeance. That’s extremely important, the continuous acts of vengeance that confirm the State is not responsible for everything; there’s also human nature.

Talking about the testimonies of the sicarios, it’s interesting that you want to know what they felt exactly in the moment when they took someone’s life. But what do you feel when they are sharing with you these striking stories?

Making the film is complicated, emotionally. Every documentary is complex because of the emotional bonds one establishes with the respective reality. In this case, everything was very psychological.

I’m the first filter of what the viewer will later feel. It’s a bomb full of doubts. It’s not just feeling indignation, or erasing the indolence, but also questioning if it’s right to do it, if you have the right to share a confession. The sensation of sharing a secret - though everyone is aware that I’m there with a camera - is complicated and involves the ethical concepts of making a documentary.

Of course it’s difficult to go home and worry about the cereal, paying the bills, because it touches your daily life, and you start losing interest in the simple things like the reunions with friends or just going out to the cinema, at least during the process.

Watching evil to the eyes is complicated because it goes beyond the fear and the judgment. It’s something that you live in solitary, because the close environment can’t understand, and it’s only shared with the people who have been through the same; I talked with Daniela Rea about this, how it affected me, and she talked about her own experiences.

Tackling the esthetic of the documentary, I imagine not everyone asked for the anonymity through the masks…

Not, only two actually, the soldier and the federal policeman asked for anonymity.

Though everyone wear the masks, their feelings are clearly expressed when they tell the stories. The masks sort of indicate everyone is afraid and in the end there’s the testimony of the woman who says she is no longer afraid…

Because she already lost everything. That’s it. The mask is the image of terror, and I thought it was going to be unforgettable. My main concern was in two things: if the mask reduced the possibilities for empathy, as the spectator is not looking the faces, becoming only an exercise in form, not even esthetic. I don’t believe in documentary when everything relies on the form, because for me the important thing is the testimony.

My other concern was in the idea that I was making a film that removed the names and faces of the victims, in a country that demands quite the opposite. It was risky. I spoke with organizations to know their opinion, because that’s the only judgment I think is legit in the ethical sense of erasing the victims’ faces or putting them on the same level with the offenders. When they [the organizations] agreed with me, my ethical concerns ended.

The esthetic can help the narrative because the esthetic was not irresponsible. I think films like this one, made in this country, are a little irresponsible if they don’t think like that, because the things are happening and it’s not the same to make Cartel Land, traveling to Mexico for six months and then returning to another reality, as to live in Mexico being part of the problem.

The mask, which emulates a medic mask, has a lot of meanings and symbols, so the lecture that you make of the film can be even more complex than what I was thinking when I was making it. That’s cinema.

In terms of structure, the documentary starts with the victims and before knowing the outcome of their cases, we see everything that’s going on - with the sicarios, the soldiers, the policemen - to later return to the victims and find out there’s no hope at all. I can’t ask you what’s going to happen, but where do you think the situation is going to?

The present indicates this is going to continue. Justice is corrupted, impunity is the right of the power, everything has an economic value and people’s top aspiration is possession and accumulation. So this will continue.

Like in all wars, because this was a war, I think commissions of the truth will be created. I believe we will have to do that exercise soon, and I just hope victims have a voice and complex subjects like forgiveness and vengeance are discussed.

Justice by own hand is what federal policemen do, as well as the autodefensas, many of the victims and the criminals themselves. The sicarios doesn’t enter to the organized crime just because they’re bad, or maybe not even because of that, they also enter in order to commit an act of vengeance, wanting to avenge the murder of a brother. That’s a never-ending chain.

The ending of the film is distressing, but I don’t see another scenario that’s not hopeless, at least not today. Hundreds of victims without an answer, more than thirty thousand families without finding their bodies, with a direct or indirect participation of the forces of public order, of the authorities… I can’t find a different scenario.

Unlike other films, I can’t find the beauty in this. For me this is atrocious. That’s also why I decided to make a film with few elements, raw, because for me there’s nothing lyrical about what’s happening.

During the screening I attended there was complete silence during the entire duration of the film, something that nowadays is definitely rare.

Each screening of this movie invites the spectator to a requiem. There’s respect and empathy for the person that is giving the testimony. It generates a very particular type of silence, I would say indelible. There’s compassion, even for the sicarios.

That’s relevant, that catharsis that makes us think as a society if we are responsible for the atrocity, the corruption, the impunity, the exercise of power, the classicism… because that’s terrible: you don’t see businessmen talking here.

The victims are mainly people that lived the Operativo Conjunto Chihuahua, the arrival of the army and the federal police there, the construction of international bridges, the forced displacement to exploit the land, and so forth. All the madness that was the so-called war on drugs.