For Lazopoulos, film is a dream. "While I was studying Psychology, I became interested in dreams and that is the main thing that draws me to film because, for me, films are dreams. Film language is a kind of dream language. I want the plot and characters to be real but I want there to be a dream quality. I don't want to make a dream into a film; I want to show life in a dreamy way."

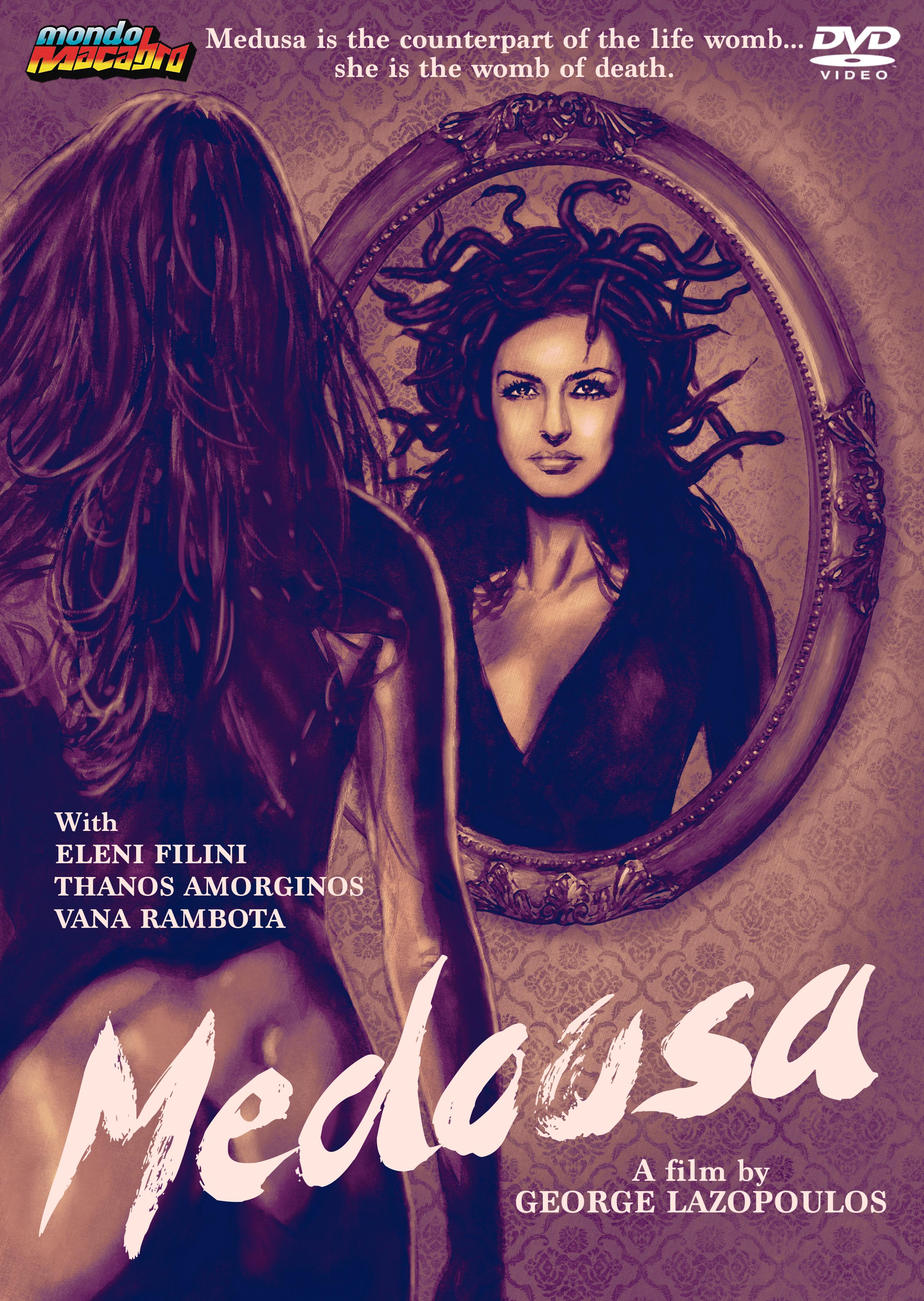

This view is the key to unlocking Lazopoulos' sole film. It's not that Medousa is overly complex; it's that it doesn't present itself in a manner of the typical genre film. While this is the Achilles heel of many films, it serves as Medousa's greatest strength, because, while the film is far from flawless, it emerges as a fascinating composite of styles and ideas, presented in a cohesive and beautiful manner.

Medousa cherry picks from the classic myth, taking the elements that fit a modern context and dispelling those that do not. In the film's prologue, Perseus is taken away from the city by his mother to live with her fiancé and his ghastly sister in rural Greece. He adapts to his newfound life until the day that his mother mysteriously vanishes. Ten years later, Perseus has worked his way up the ladder of the seedy underbelly. When by chance his partners in crime, a group of radical punks/metalheads living a faux-anarchist lifestyle but driven by capitalist desires, target his childhood home for their next robbery, Perseus is faced once again with the mystery of his mother's disappearance.

Like most mythology, fate plays an important role in Medousa. This is the distinction that sets it apart from the typical horror film, where character's actions lead to their outcomes. The characters in Medousa, rather, are driven by a sense of preconceived determination. Lazopoulos' script is tight and most elements introduced come back into play in a crucial way. These fated results work in favor of the film's benefit. One of the most important of these aspects concerns Perseus' evolution to hero. Rather than don a sword as did his literary basis, Perseus is drawn to knives from a young age. His fascination leads him to train under a local knife thrower, and, over time, he masters the art of blind knife throwing. When Perseus finally comes into contact with Medusa in the climax, it is this skill that serves to help him defeat her.

If modernized mythology serves as the basis for an important arc of the story, Lazopoulos complicates the narrative structure by adding a secondary police procedural arc. This secondary plot line deals with a team of detectives who end up on the tail of Medusa when her petrified victims start showing up all around Greece. Medousa's police-procedural element also imbues the film with a neo-noir aspect. A style fitting for the resurgence of interest for the genre in the 1990s, and heightened by Vassilis Kapsouros's colorful and gritty cinematography.

With influences ranging from Dario Argento to German Expressionism, the film has a notably anachronistic feel to it, where it looks as if it could have just as likely been shot in 1970 or 1980 as it was in 1998. This was Lazopoulos' goal, as he felt that the film would gain from not being fixed in either time or place: "I didn't really want to say anything about current times. I wanted Medousa to have an appearance of today but it wasn't really specific; it could be anytime. I never liked to fix things in time or place."