70s Rewind: THE CARS THAT ATE PARIS, Peter Weir's Mysterious, Motorized Movie

With Furious 7 hitting theaters over the weekend and excitement building about the release of Mad Max: Fury Road next month, I was in the mood for an Australian car movie.

Director James Wan, by the way, was schooled in Australia, and cites Mad Max as an influence on Saw. (See Mark Hartley's excellent documentary Not Quite Hollywood.) Director George Miller, in turn, was a product of the Australian exploitation scene in the early 1970s, making his first short film, Violence in the Cinema, Part 1 in 1971 as he was completing his medical studies to become a doctor.

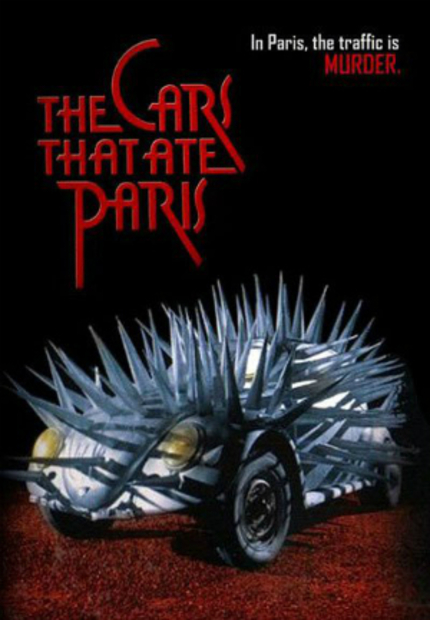

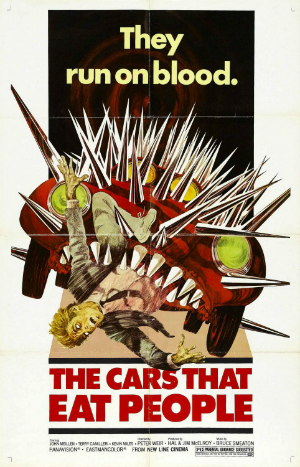

Peter Weir, slightly older than Miller, began directing television shows at the tender age of 24. He made a slew of short films before The Cars That Ate Paris (aka The Cars That Eat People), which played at the Cannes Film Festival and gained international distribution in 1974, though it was his two subsequent features, Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and The Last Wave (1977), that more firmly established his reputation for quiet, atmospheric, and rather mysterious filmmaking.

Those two films frequently played Los Angeles repertory theaters in the late 70s and 80s, which is how I first saw them. (I was thunderstruck.) Finally catching up with The Cars That Ate Paris, however, showed me what I'd been missing all these years. Without spoiling things, it's fair to say that the movie features its fair share of furious car action, and so is satisfying on that level for fans, such as myself, of motorized mayhem.

Yet it also shows that young Weir was already in command of a personal aesthetic that would continue to set him apart from other members of the "Australian New Wave" over the coming years. Cars begins with largely wordless scenes that set up the curious, haunting, and mysterious tone, as two men in a ramshackle car travel through the Australian countryside in search of a new life.

Things do not end well for one of them, and the other is revealed to be his brother, a shy man named Arthur (Terry Camilleri), who wakes up to the tragedy in a small town called Paris. The local citizens are wary of the newcomer, all except for The Mayor (John Meillon), who puts up Arthur in his home while he recovers and appears to be quite welcoming.

The Mayor's apparent warmth, however, is a cover-up for the town's bizarre, evil intentions. For reasons that are never explained, the very isolated town has a habit of causing automobile accidents. The hapless victims who survive with severe brain injuries are hospitalized in a local facility; all others are put to death. The citizens of Paris divide up auto parts and victim's possessions, and wait for the next car to make the mistake of driving by.

It's a strange and mysterious movie, and at the same time a wonderfully compelling story. It's as though everyone in town has been dreaming the same mundane fantasy for years, to the point that their reality has become utterly twisted and deranged. For whatever reason, The Mayor believes that Arthur will fit in quite nicely, and so Arthur makes every attempt to do so, trying on a couple of jobs for size; he's so meek and mild and mortified by his own past sins that he doesn't believe he's worthy of anything else.

It's a strange and mysterious movie, and at the same time a wonderfully compelling story. It's as though everyone in town has been dreaming the same mundane fantasy for years, to the point that their reality has become utterly twisted and deranged. For whatever reason, The Mayor believes that Arthur will fit in quite nicely, and so Arthur makes every attempt to do so, trying on a couple of jobs for size; he's so meek and mild and mortified by his own past sins that he doesn't believe he's worthy of anything else.

Weir walks a tightrope, balancing mundane performances -- cheers to Bruce Spence for bringing life to his joyfully off-balance character -- with the oft-kilter narrative. The pace sometimes drags, but as Weir's subsequent filmography would show, that's also a characteristic of his work, and, I've concluded, an indicator to allow time for the audience to ponder the broader implications of what's happening on-screen. Eventually, things pick up in a manner that's reflective of the narrative, and we even get to see gnarly cars that bear a foregleam of the vehicles that would populate Mad Max 2 (aka The Road Warrior) years later.

Best of all, even in this early film, Weir demonstrates his greater interest in stirring up questions than in supplying answers. The Cars That Ate Paris is a marvelously chaotic picture that asserts its artistic individuality, but not by belting the viewer across the mouth. Instead, it injects a slowly-developing poison directly into the bloodstream, suggesting that all civilization is merely an illusion, waiting to be dissolved.

70s Rewind is an occasional series on the writer's favorite film decade. The Cars That Ate Paris is available to watch in the U.S. on the Hulu Plus streaming service, via its Criterion collection section.