Destroy All Monsters: BOYHOOD And The Experience Of Now

"Suppose your life a folded telescope

Durationless, collapsed in just a flash

As from your mother's womb you, bawling, drop

Into a nursing home. Suppose you crash

Your car, your marriage - toddler laying waste

A field of daisies, schoolkid, zit-faced teen

With lover zipping up your pants in haste

Hearing your parents' tread downstairs - all one." - X.J. Kennedy

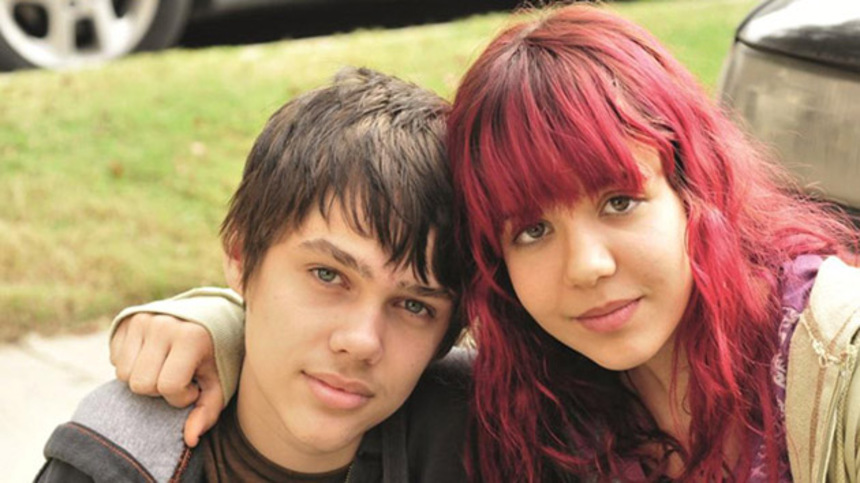

Film is a temporal archive, and Boyhood is the most magnificent ever built. Boyhood coalesces boyhood down to a breathless, 3-hour supercut, and whether you call its core conceit (the filming, over 12 years, of actor Ellar Coltrane in a series of dramatic scenes as he ages from 6 to 18) a creative masterstroke or art-school gimmick, the effect is the same.

That I found the rapid onscreen aging of Ellar/Mason (for the purposes of this consideration, it's fruitless to divide them) enthralling is unsurprising. Series as far-ranging as the Antoine Doinel and 7-Up films have been leveraging this beguiling reality of filmed moments involving young people to greater and lesser effect for, and over, decades. When Harry Potter, Part 8 was on its way to theatres I went to the Cineplex once a week to watch the preceding seven films. Though the dramatic impact of Harry/Daniel, Ron/Rupert and Hermione/Emma's maturation on the weight of the franchise was purely collateral, there was no denying it, either.

Watching kids grow up is one of the great, poignant fascinations of adult life, for every single obvious reason and several that aren't. But film doesn't just watch - it scribes.

Whether you believe that film is truth at 24 frames per second or a lie at 30, one thing remains inescapable: unless there are digital apes involved, each shot is a record of an actual moment that happened. Something stood before the camera as the media wound through the mechanism.

Most filmmaking (including those apes) is the generation of great artifice to surround, support, and recontextualize that something into something like something else, and Boyhood is no exception. It is a nicely-staged, ably-performed drama. Beneath the film's artifice, though, there is still the core, imperturbable reality: Just look at him! He's growing like a time-lapse Venus flytrap, right in front of your face!

This is what Boyhood is built on, not its own dramatic construction: the high-speed visual effect of maturation, like that music video where, in each shot, the singer's pregnant belly is sticking just a little further out of her shirt; or those Vimeo videos where photographers' daughters roar from terrible twoness to equally terrible tweenhood in the span of minutes, set to the beat of an OK Go song.

By dint of the images it chooses to show us vs. the images it leaves out, film does not merely present; it connects. I steered clear of the trailers for Boyhood because I wanted to delight in that process as it was occurring in the film's, not the trailer's, version of fast-forward.

I never dreamed that that kid would turn into that kid, by way of a chunky middle. Ellar/Mason isn't much like me, but I feel weirdly attached to him, as I presume most people will. We've spent a lot of time together, even if it was only three hours; and if our life cycle flyover together wasn't exhaustive, it still feels as though it was representative.

The pressure to be an omnibus representation of a child's lifetime should overwhelm the film, but instead, the opposite is true. Here's how I think it did it: Like a kind of Tree of Life for not-assholes, the movie makes drama out of childhood memory, but does so by breaking those memories down to their mundane, relatable roots, rather than exalting mundane roots with hosannas to the highest.

Boyhood is about families, and it is about them in a very progressive way. This film, which could not be more quintessentially American in its way, systematically obliterates the failed American notion of the nuclear family. The family around Ellar/Mason waxes and wanes, and Boyhood chronicles, and never comments upon, the overlapping spheres of influence that lie upon Ellar/Mason throughout his twelve years with us.

The family always contains the mother (Patricia Arquette) and the sister (Richard Linklater's daughter, Lorelai). It often involves the father (Ethan Hawke, whose library of temporal transformation at Linklater's hand will deserve a special kind of Oscar if and when the actor retires), and through him, the father's second wife and their young baby; by her, we gain a pair of step-grandparents who give Mason his first bible and teach him how to fire a gun. Sometimes, the family expands to include Mom's increasingly-abusive second husband, who is an alcoholic; and through him, there are two step-siblings, who become part the cabal until they are left behind and never heard from again.

These collectives - families within families, rings within rings - are what they are. As bearers of circumstance (homes, cars, siblings, jobs), the family and its participants move Ellar/Mason along through life, in the much same way we all were moved through ours.

But by presenting so much context, Boyhood seems to move away from context as a plot driver; it seems to successfully move away from "plot." Arguably, stepfather #1 is a real asshole - but is his time with Mason "good?" "Bad?" Or merely "context?" Does it push the boy left or right on the path to adulthood? Was there even a fork in the road? It doesn't, ultimately, matter - and Boyhood knows better.

It's a brilliant anti-narrative strategy. There's no traumatic car crash scene with drunken stepfather #1; there isn't even an explanation, later on, for how or why Mason's mother has left stepfather #2. He's just gone. It was years ago. We're here now.

In Boyhood we're always "here now," with no moody dissolves or title cards to dog-ear the pages of the book. This is boyhood, and this, I think, is the point.

There's an idea in meditation that the goal of the process is to practice how to place one's attention, and to do so by placing it on this moment, the one occurring right now, by focusing on the breath, the most "now" thing that any of us is doing at any given time.

Boyhood is a movie about the most "now" things that are happening at various interspersed moments in Ellar/Mason's life. Ellar/Mason helpfully circles this idea for us in the film's final scene, when he sits in the desert of a Texas state park, high on something or other with a pretty girl beside him, and blurts out, "it's like it's always right now."

It's the kind of bullshit-enormous revelation that any number of us probably had in our teens and/or under the influence of psychotropics, and it is so bullshit and so enormous precisely because it is so abjectly true. The pronouncement underlines the point of the whole affair - not just what Boyhood was about, but the way it was about it.

Boyhood, a collection of so many moments, is about this moment. The film is about that experience, the experience of now; if Ellar/Mason arrives at any grace by film's end, it is that he has come to understand (at least temporarily; adulthood tends to rob one of this insight) that the only thing that means anything is what's happening right now.

Ordinarily, a movie like this would seem designed to make me feel old - the experience of watching Ellar/Mason grow up; the monumental artistic achievement by Linklater and his team. But not here. I've spent the time since seeing the film wandering back and forth through its three hours / twelve years, lost halfway through a Waking Life daydream that I can't seem to wake up from. It's good. And Boyhood makes me feel young.

Destroy All Monsters is a weekly column on Hollywood and pop culture. Matt Brown is in Toronto and taking a summer break from twitter.