"We're Doomed. ... Sayonara."

by Peter Martin

As a child, I saw the butchered Americanized version multiple times, the one with Raymond Burr reporting on the devastating damage wrought by a 150-foot prehistoric monster. On a nine-inch television, to a child, it was completely convincing and utterly terrifying.

I'd heard that the original, Japanese-language version was very dark in its tone and quite direct in its linkage of the monster to the horrors of the atomic bombs dropped on the country. Nonetheless, when I finally saw it, I was still surprised by the pitch-black mood created by director/writer Honda Ishira, his co-writer Murata Takeo, and their collaborators. On that viewing, the anger came through strongly, the feeling that innocent Japanese people had suffered greatly through no fault of their own.

On a very recent viewing, I was struck by different emotions. Early sequences depict the mysterious sinking of fishing boats and the reaction of family members desperate to know what has happened to their loved ones. They push back against the authorities: 'Why aren't you doing more? What aren't you telling us? We need to know now!' Naturally, I thought of family members of the passengers and crew of the lost Malaysia Airlines jet, and the even more recent South Korean ferry that sank with hundreds of young people on board. The desperation is now, sadly, familiar, the feeling that the forces of nature are aligned against mankind, even as man himself is falling into an ever-widening abyss of his own making.

It's easy enough to pick the movie apart for its effects, especially on a big screen. But that would be churlish, and misses the point anyway. More than the monster's rampage, I think of the faces, bawling children violently orphaned, scarred for life, or the television announcer, broadcasting until the last moment: "We're doomed ... Sayonara."

Godzilla Is Our Nightmare, and We Are His

By Ben Umstead

Unlike some children I know now, my childhood was neither ruled nor peripherally adorned by the King of the Monsters. Sure, Godzilla was around... in that I was aware of him (I had some cheap plastic toy and remember renting the god awful NES game), but I suppose it was my own snobbishness that kept Godzilla and friends at bay during my play. See, I saw some of the later films from the 60s and 70s dubbed in English. I couldn't stand dubs, so Godzilla became a non-event by my own choosing really. Now that doesn't mean I haven't always been intrigued by the big guy. I have. So when the American Cinematheque announced they'd be screening Honda Ishirō's original I knew now was the time to give "Gojira" a proper hello.

It's easy to grasp the film in a historical perspective, as it's absolutely a defining precursor and influence on our modern blockbusters. Fans will no doubt know Honda's original has some potent, incredibly relevant and disturbing imagery. But I was not ready for how hard it was going to shake me. If Planet Of The Apes is still a key marker for cinematic allegory on race and class, than Godzilla is the touchstone for cautionary tales of the atomic age.

Heck, it's easy to forget that this film came out not even a decade after the bombs were dropped. The sympathy that is shown towards this so called monster is rather astounding, no doubt moving, and a sure sign as to why children love Godzilla. It's not merely because boys, especially, like the idea of destruction, it's because Godzilla is misunderstood, out of time, homeless essentially, disturbed and spurred on and haunted by humans. In turn, children own their nightmares, seeking them out in ways adults rarely do. They find solace in turning their nightmares into powerful allies. Godzilla is our nightmare and we are his. It's a vicious cycle to be sure, and makes for rousing, thoughtful and indeed sometimes cheeky cinema.

How Japan Is Remembering

by Christopher O'Keeffe

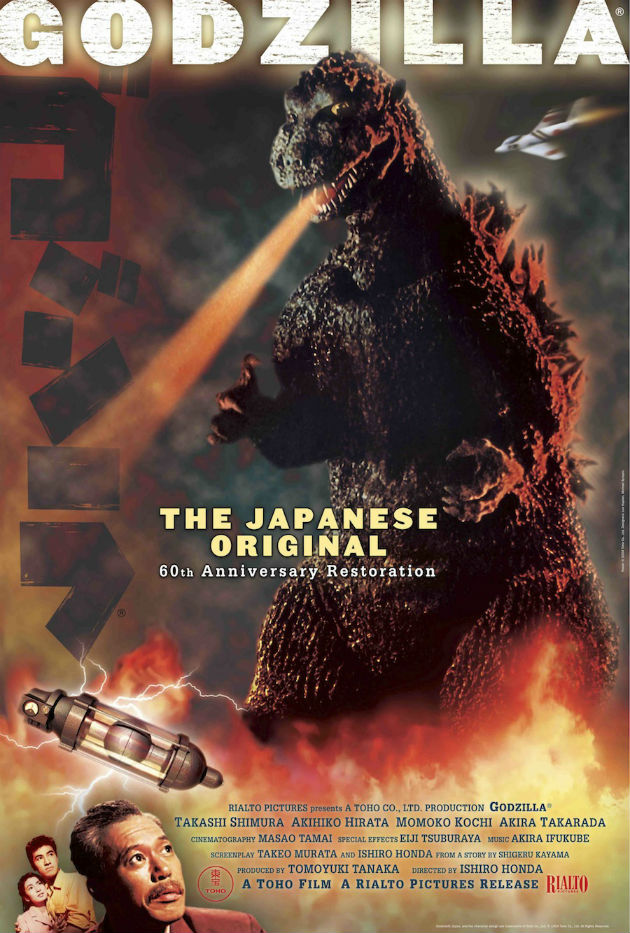

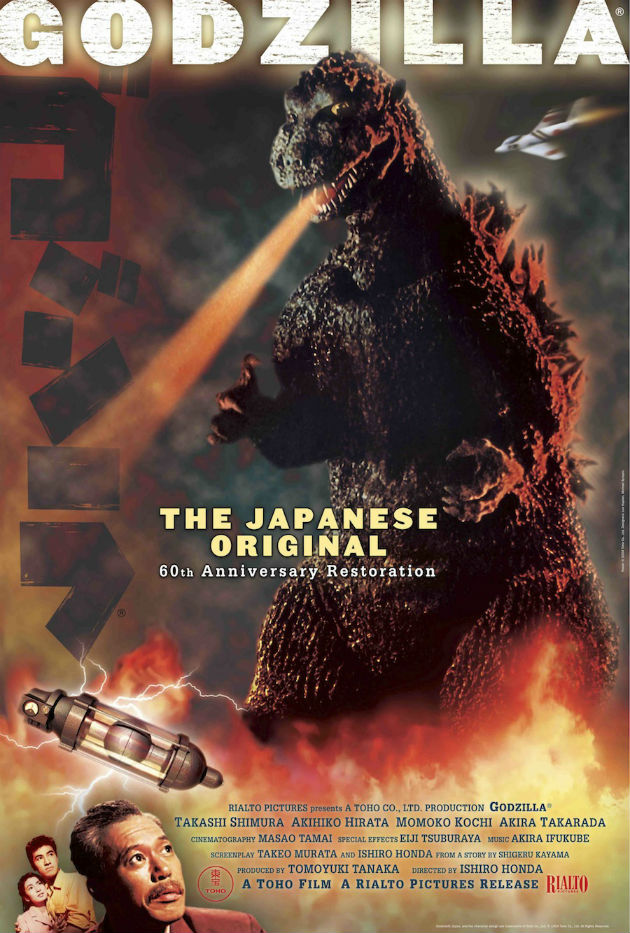

While excitement builds abroad for the arrival of Gareth Edward’s take on Godzilla, it’s only fitting the beast will also be rising from his atomic slumber in the country of his nuclear creation, Japan. It’s 60 years since the birth of Gojira and in a country where Godzilla, and the ‘Kaijyu’ genre of monster movies he inspired, has remained huge, the film will be getting a suitably wide run in cinemas around the country. The film has been digitally restored for this release and will open on June 7.

Any residents of Japan with access to a TV may want to splash out on a subscription to the Nihon Eiga Senmon Channel, where they are showing every film in the Godzilla series, starting with the original and running through to 2004’s Godzilla: Final Wars. The programming started in March but you can still catch the end of the Showa series of films from 1973’s Godzilla vs. Megalon. Check out the site (Japanese only) for a rundown of the films, and also for this cool map showing the spots that Godzilla has destroyed on his run thus far

Map of Destruction.

Digitally remastered original.

Nihon Eiga Senmon Channel.