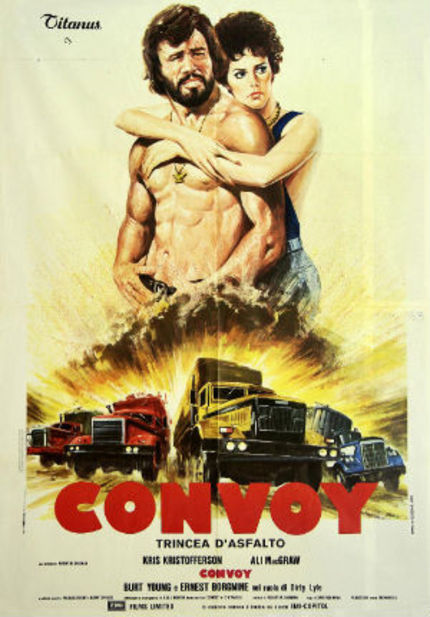

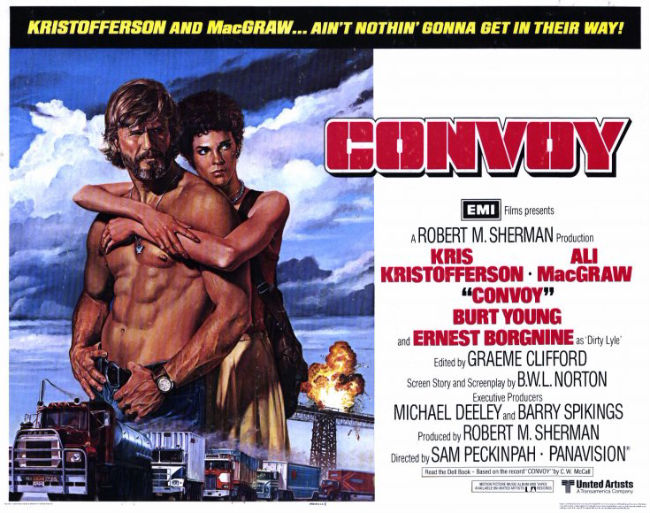

70s Rewind: CONVOY, Sam Peckinpah's Frustrating, Perplexing Trucker Movie

"They're all following you." "No they ain't. I'm just in front."

Convoy looks like something a longtime heavy smoker might cough up on a particularly bad morning. Reportedly, Sam Peckinpah was at a low point, suffering from the effects of alcoholism and drug abuse, and could barely function as a filmmaker. Friends stepped in to help out; James Coburn is credited as one of the second unit directors, and according to David Weddle's 1994 book If They Move...Kill 'Em!, he shot much of the film while Peckinpah remained in his on-location trailer.

Debatably, then, the final product may be viewed more as a pastiche than the singular work of a genuine auteur. Yet, even though Convoy fails to congeal into a satisfying whole, individual sequences peek out from the mess, tantalizing the attentive viewer with lost possibilities ...

... as when a half-dozen trucks detour onto a narrow dirt road, kicking up magnificent, rolling clouds of dust as they pass slowly and majestically up and down through rolling hill country ...

... or when a parade of 18-wheelers sail along blacktop highways at dusk and on into the night, their passage marked only by the tiny colored running lights adorning the muscular beasts ...

... or when an extended fight breaks out in a roadside cafe, as truckers attack police officers and chairs and tables are smashed and the physical violence is choreographed like a saloon brawl from a Sam Peckinpah Western ...

... or when Ali MacGraw (as an ill-defined photographer) refers to a growing convoy of trucks and tells Kris Kristofferson (as an ill-defined anti-heroic truck driver known as Rubber Duck): "They're all following you." And he replies: "No they ain't. I'm just in front."

That about sums up the movie's incidental charms. Whatever fleeting pleasures are to be found, they seem to have been accidental.

America has always been in love with the open road. In the post-World War II era, this eventually led to the Interstate Highway system, which tied together major cities with multi-lane slabs of behemoth concrete -- and also decimated myriads of small businesses and small towns which were bypassed. (For a crash course history lesson, see Pixar's Cars.)

America has always been in love with the open road. In the post-World War II era, this eventually led to the Interstate Highway system, which tied together major cities with multi-lane slabs of behemoth concrete -- and also decimated myriads of small businesses and small towns which were bypassed. (For a crash course history lesson, see Pixar's Cars.)

My family vacations were (almost always) taken on the road, with my father behind the wheel as we drove hundreds, and ultimately thousands, of miles across the country. As I approached driving age, my father taught me about road etiquette, including the need to show respect to the long-hauling truck drivers, who worked long hours and often toiled on little sleep.

In 1973, the oil crisis hit the U.S., and the government imposed a national highway speed limit (55 miles per hour) the following year. That affected truck drivers to a disproportionate level, since they were invariably paid by the mile and so earned less for the same effort. Truckers already used CB (Citizens Band) radio to communicate on the open road; the lower speed limit spurred increase usage as CB radio became a means to alert fellow drivers to the presence of law enforcement.

The credited source material for Convoy is the song of the same name, a novelty tune composed and performed by C.W. McCall (AKA Bill Fries) that ruled American pop radio for long, merciless weeks in 1975. (A different version of the song was recorded for the movie version, to reflect its plot and character names.) But the more direct inspiration was probably Hal Needham's Smokey and the Bandit, released in May 1977, which depicted the battle between Burt Reynolds' renegade Bandit and Jackie Gleason's Sheriff Buford T. Justice as they sped down highways and byways of the American South. (Jerry Reed's truckdriving character Cledus played a supporting role.) The film earned $126 million at the box office -- $450 million in today's money, if adjusted for inflation -- and inspired a string of country-fried imitators.

Bill L. Norton (AKA B.W.L. Norton) is credited with the screen story and screenplay, though Peckinpah reportedly was unhappy with the script and encouraged the actors to re-write dialogue and improvise at will. Kristofferson growls his lines, as is his wont; MacGraw utilizes her usual "deer caught in the headlights" performance style; Burt Young and Franklin Ajaye are present but undistinguished as truck drivers; and Seymour Cassel is thoroughly unconvincing as New Mexico state governor. Ernest Borgnine stands out as an evil sheriff, mostly because he appears to relish the opportunity to chew the scenery and does so without a trace of self-conciousness.

Bill L. Norton (AKA B.W.L. Norton) is credited with the screen story and screenplay, though Peckinpah reportedly was unhappy with the script and encouraged the actors to re-write dialogue and improvise at will. Kristofferson growls his lines, as is his wont; MacGraw utilizes her usual "deer caught in the headlights" performance style; Burt Young and Franklin Ajaye are present but undistinguished as truck drivers; and Seymour Cassel is thoroughly unconvincing as New Mexico state governor. Ernest Borgnine stands out as an evil sheriff, mostly because he appears to relish the opportunity to chew the scenery and does so without a trace of self-conciousness.

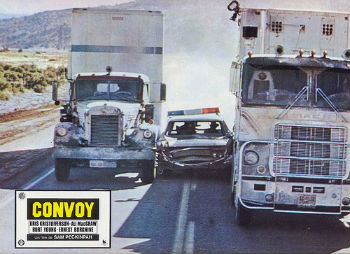

The story, such as it is, follows Rubber Duck as he and his fellow truckers make a run for the state line to escape the wrath of an evil sheriff, who wanted to lock up one of their buddies on a trumped-up charge. Other truckers join the convoy, other law enforcement agencies get involved, the media gets wind of it, politicians insert themselves, 'the people' rally to the side of the truckers ... all for no apparent reason.

Rubber Duck doesn't have a cause, or any kind of social or political statement to make, he's just 'running for his life,' as he says. If other people choose to follow, that's up to them. And within that premise, a kernel of a compelling idea resides, an examination revolving around the absence of true leadership and the seemingly innate need and/or desire for the common man to be led.

Instead, the movie is more interested in watching trucks crash through hard turns and smash through buildings in slow motion. So, yes, Convoy is a mess, but it's a Sam Peckinpah mess, and that makes the movie a fascinating, if perplexing and frustrating, experience.

Convoy is available for U.S. viewers via Netflix Instant until Wed. June 27, 2012. Netflix uses the version issued on Region 1 DVD by CheezyFlicks.com in 2005; the picture quality doesn't look very good. This edition is also missing several minutes of footage that was included in other editions.

The movie has been issued on Region 2 DVD at least twice, once by Optimum Entertainment (UK) and once by Kinowelt Home Entertainment (Germany).

Picture credits: Movie Goods | Greatest Movie Ever! Podcast | Samuel Owen Gallery