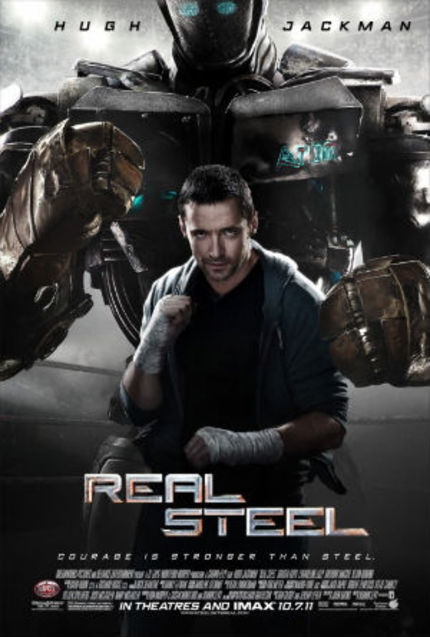

REAL STEEL Review

If I was an 11-year-old boy, I'd love Real Steel. It's strictly a young boy's fantasy, a flight of fancy, a bout of wish fulfillment, in which your mother suddenly dies and you don't care, because you have a big robot toy and you're always the smartest person in the room, and everyone loves you, and maybe you can finally connect with the father who abandoned you.

Like I said, a fantasy for boys; girls not welcome, unless they know their place.

The first ten minutes of the fantasy is entirely warmed-over material from many other films and television shows: a character making static sounds with his voice to pretend that his cell phone has a bad connection; the same character making a bet beyond his means that he is guaranteed to lose; the same character allowing himself to become distracted by a pretty girl he will never see again, solely so he can lose the bet beyond his means; the very same character learning that the ex-wife he hasn't seen in 10 years has suddenly died and that he has now inherited custody of an 11-year-old son he has rarely or ever visited.

Hugh Jackman plays the irresponsible character named Charlie Kenton. The movie is set in the near future, where robots have developed to the point that they have replaced human boxers. (Curiously, the robotics industry has decided to make their advanced systems available only to people involved in the sweet science of boxing.) Charlie, a former boxer himself, has become a robot boxing promoter, traveling around the country with a series of robots in his 18-wheeler. And then one day his latest robot goes kaput, losing to a steer in a bout arranged by rival promoter Ricky (Kevin Durand), and Charlie is reminded that he has a young son who needs him.

Charlie wants nothing to do with the kid, and he can barely get to court quickly enough to sign away his custody rights when he realizes that his ex-wife's sister (Hope Davis), who wants to adopt the kid, has married Marvin, a very rich man (James Rebhorn). That prompts Charlie to negotiate a secret deal with Marvin, in essence selling his custody rights so he can buy a new robot, and agreeing to keep the kid over the summer so Marvin can enjoy a vacation trip with his lovely, much younger wife.

Even then, Charlie tries to dump the kid on his long-suffering girlfriend Bailey (Evangeline Lilly) so he can go back on the road. But the kid, named Max (Dakota Goyo) is a genius in science, technology, public speaking, and emotional manipulation, and he quickly gets his way with Charlie. Eventually, Max finds his own robot to play with, outsmarts everybody, and pushes Atom (as he christens his robot), and Charlie toward championship glory.

Any attempt to discern adult meaning from the story is rebuffed by the film's insistence on catering to the desires of 11-year-old boys the world over. Even though Max has suffered the loss of his mother, the only parental figure he has ever known, he never demonstrates any evidence of grief for her, not even mentioning her passing. He is preternaturally gifted and well-spoken beyond the norm, imbued with incredible self-confidence, yet we must imagine that all these things come naturally to him, that no one helped him or molded him in any way. He is a product of his own imagination.

Charlie is a likable loser who doesn't drink, smoke, gamble, or cheat on his lady. He doesn't care much about material things, and isn't bothered by the lack thereof. His biggest faults seem to be that he is not good about paying back debts, and he has studiously avoided providing for his son. There is no doubt that both issues will be addressed before the movie ends, which contributes to the feeling that this is a movie without anything at stake.

And that makes it very hard to care what happens between Atom the robot and whatever robot opponent he happens to be facing on his slow journey to the top. The visual effects work is truly superb, with the robots integrated seamlessly into the live-action footage. But how can we care what happens to robots without any semblance of personalities? The villains who control the "bad" robots are never more than glaring figures seen from a distance, and nothing that happens to the robots seems to have any effect at all on the relationship between Charlie and Max.

If you fit the target demographic and / or you're desperate to see computer-generated robots beating the crap out of each other in a confined space, help yourself. otherwise, I'm afraid there's very little in Real Steel that will be remembered after the cash registers have stopped ringing.