Hollywood Beat: Michael Clarke Duncan Dies; Wachowskis and CLOUD ATLAS; REVOLUTION on TV

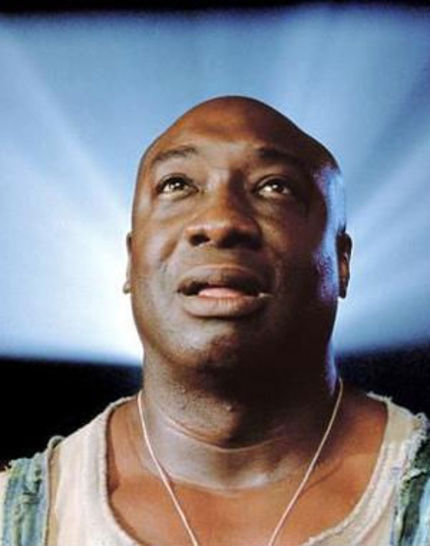

Why Michael Clarke Duncan? When the actor unexpectedly passed away on Monday at the age of 54, messages of grief and support flooded onto social media, beyond what one might expect.

He was a character actor, not a "star," not in the sense of the word that we have come to associate with movies and television. The former bodyguard was consistently busy throughout his too-short career, even before his performance in Michael Bay's Armageddon introduced him to a much wider audience. True, most of those roles were bit parts, the kind that describe the character by profession rather than name: "Security Guard," "Bouncer," "Huge Guard," "Bodyguard," and "Bouncer."

Rising six feet, five inches tall, with an imposing bulk, he could easily have played a prison guard in Frank Darabont's The Green Mile, but as John Coffey, a convicted child murderer, he instead laid bare his heart. For his performance, he was nominated for an Academy Award.

Though his build and his scowl qualified him to play many a villain, his gentle, open-hearted spirit always seemed to peek through, and in many of the tributes that I've read, that seems to be a recurring theme. Years ago, when I lived in Los Angeles, I remember a co-worker talking about an actor she'd met at a party: 'He was a real jerk. That's why he's always playing jerks; when casting agents see a part for a jerk, they think of him first.'

Somehow, I think that whenever directors and casting agents thought of gentle giants who could handle light comedy and dark action with equal aplomb, they thought of Michael Clarke Duncan first. And so did his fans. But none of us ever thought he would be gone so soon.

Months before The Green Mile was released in 1999, The Matrix stormed the box office and made virtual reality, black leather, and "bullet time" hot items among the general moviegoing public. The Wachowskis followed that up with two sequels of diminishing interest before bouncing back, as it were, with Speed Racer, a blitzkreig bop of pop that blew out my cheap Blu-ray player. (Not really, but it's the only one the player couldn't handle without breaking up into a million pixels.)

Months before The Green Mile was released in 1999, The Matrix stormed the box office and made virtual reality, black leather, and "bullet time" hot items among the general moviegoing public. The Wachowskis followed that up with two sequels of diminishing interest before bouncing back, as it were, with Speed Racer, a blitzkreig bop of pop that blew out my cheap Blu-ray player. (Not really, but it's the only one the player couldn't handle without breaking up into a million pixels.)

Now they're back with Cloud Atlas, which they wrote and directed in collaboration with Tom Tykwer. The film has its first public screening at the Toronto International Film Festival on Saturday night (September 8), and we hope to have a review up just as soon as possible.

If, like me, you're waiting for word on the film from afar -- and wondering how on earth anyone could translate David Mitchell's incredibly complex book into a movie -- I can heartily recommend Aleksandar Hemon's profile / "making of" article in this week's issue of The New Yorker, which is available to read free of charge at the magazine's website.

Hemon is a novelist and short-story writer, and also on friendly terms with the siblings from his time working with them on a film project, so this is not a 'warts and all' profile, yet it sounds as though the notoriously press-shy Andy and Lana Wachowski opened up to him in a very sincere manner.

What emerges is a sympathetic account of Lana coming to terms with being a transgender individual, and the extremely close personal and working relationship that Lana and Andy enjoy. We get a peek at the perks of success -- they rent a house in Costa Rica near the ocean so they can work on the script with Tykwer -- but also a look at the practical side of filmmaking, as they break down the novel into colored index cards and try to piece together a narrative structure that would work as a film. And it seems that much of their process may be intuitive:

When I asked why Lana was always the one looking through the viewfinder, while Andy covered the sight lines and the over-all architecture of the shot, they were stumped by the question.

All in all, it's a fascinating read.

Due to work, my movie watching has suffered lately, but I took a break and watched the pilot episode of the TV series Revolution, available in the U.S. via the Hulu streaming service. The show proposes that all electricity in the world has mysteriously vanished, leading to the fall of governments and a general breakdown in society.

Due to work, my movie watching has suffered lately, but I took a break and watched the pilot episode of the TV series Revolution, available in the U.S. via the Hulu streaming service. The show proposes that all electricity in the world has mysteriously vanished, leading to the fall of governments and a general breakdown in society.

Though it's been widely advertised as coming from J.J. Abrams, who serves as one of the executive produers, it was actually created by Eric Kripke, who created Supernatural, another U.S. broadcast TV series, and served as showrunner for five seasons. I've only seen an episode of that show here and there, but I'm aware that Kripke has a base of fans who very much enjoyed what he did.

But I can't imagine they'll be pleased with Revolution, which someone described as 'The Walking Dead Meets The Hunger Games.' Granted, it's only the pilot episode, but I don't trust any show that works so hard to induce sympathy for a character that hasn't been properly introduced. And that's what happens very quickly, as a man with a stern chin is killed thanks to stupidity, leaving behind rebellious teenage children and a plucky girlfriend who also happens to be a doctor.

The show is set up with a giant, underlying question: "Why did all the power go off? Can we get it started again?" Yet I kept asking myself, 'If civilization has gone to hell in a handbasket in 12-15 years, with food scarce, clothes filthy, and buildings overgrown by vines, why do almost all the men bother to shave?'

Giancarlo Esposito's return to TV after his magnificent run on Breaking Bad reminds that actors can only turn in good performances if they have decent material to work with. Jon Favreau directs; his efforts are on par with what he did with Iron Man 2, which is to say they are undistinguished.

It may be that more compelling plot strands may emerge, but the pilot did not effectively sell the premise or the mystery. Instead, it makes me wonder if it was simply the marketability of the premise that sold the series.

Revolution officially premieres Monday, September 17 on NBC.

"Hollywood Beat" is a weekly column on the U.S. film and TV industry.