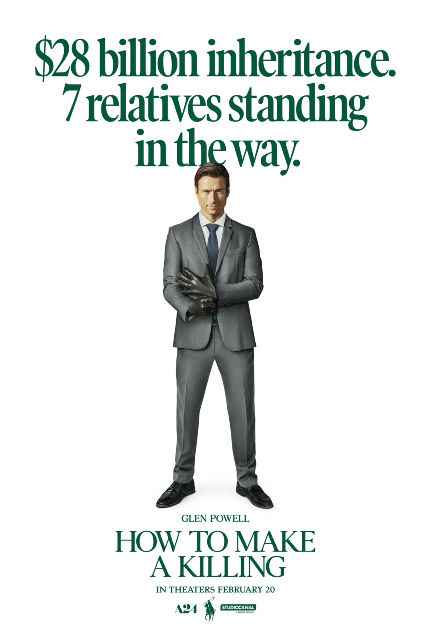

HOW TO MAKE A KILLING Review: Glen Powell Leads Surface-Deep Satire of the Rich And Not So Famous

Glen Powell, Jessica Henwick, and Margaret Qualley star in John Patton Ford's sophomore feature.

Playwright, novelist, and short story writer Roy Horniman left this mortal plane almost a century ago, but one of his novels, Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal, has remained, if not in the public consciousness directly, then indirectly.

First came the 1949 Ealing Studios comedy, Kind Hearts and Coronets. The novel then served as the inspiration for the 2013 musical, A Gentleman's Guide to Love and Murder, and now as the source material for writer-director John Patton Ford’s (Emily the Criminal, Patrol) latest film, How to Make a Killing.

A stone-cold black-comedy classic, Kind Hearts and Coronets is best remembered for its acid-tongued deconstruction of the Edwardian ruling class and Alec Guinness’s tour-de-force performance as eight members of the ill-fated, if ultra-wealthy D’Ascoyne family. Targeted one by one by a disowned heir, Louis D'Ascoyne Mazzini (Dennis Price), they died, if not spectacularly, then predictably.

As an acerbic, achingly hilarious satire on class and its discontents, Kind Hearts and Coronets has yet to be equaled, but that didn’t stop Ford from borrowing and updating the premise to contemporary New York City (actually, Cape Town, South Africa) with actor-producer Glen Powell (The Running Man, Hit Man, Top Gun: Maverick) as Mazzini’s contemporary analog, Becket Redfellow (Glen Powell), disowned before birth by a dictatorial grandfather, Whitelaw (Ed Harris, bizarrely deaged in the opening scenes), eighth in line to the Redfellow fortune, and currently living a life of unquiet desperation as an employee in a high-end menswear store.

Not quite the full-on narcissist or unreconstructed sociopath of the 1949 Price-led film, Becket doesn’t embrace the idea of killing his way to the multi-billion dollar fortune controlled by his grandfather until a long-lost childhood crush, Julia Steinway (Margaret Qualley), appears at the store, engagement ring in hand and a wealthy dude on her arm. When she nonchalantly tells him to call her once he’s murdered a few relatives, the idea awakens Becket’s long-suppressed desire to right perceived wrongs and acquire what he feels the world owes him, the “right life” his disinherited mother mentioned in his ear moments before she passed, poor and forgotten, from this world into the next.

Newly armed with the idea and seven (not eight) blood relatives ahead of him in line, Becket starts with a near-age cousin, Taylor Redfellow (Raff Law), a stockbroker and the son of Becket’s uncle, Warren Redfellow (Bill Camp), the head of a brokerage firm. At first, relying more on luck than planning, an issue bound to annoy at least one audience member out there, Becket barely succeeds, attending his newly expired cousin’s funeral, introducing himself to Warren, and, over a few short weeks or months, replacing the defunct Taylor as Warren’s surrogate son and heir to the brokerage firm.

Not content, of course, Becket targets another cousin, Noah (Zach Woods), a “self-employed” artist and photographer who describes himself as the “white Basquiat.” He’s anything but, of course, making his exit, if not exactly welcomed by the moralists in the audience, then completely predictable. Other targets of Becket’s disaffection include Steven (Topher Grace), a self-serving mega-church pastor, McArthur (Sean Cameron Michael), Becket’s uncle and a Musk-inspired billionaire “entrepreneur,” Cassandra (Bianca Amato), Becket’s aunt, and last, but far from least, Whitelaw, older, craggier, and meaner than ever.

Noah’s schoolteacher girlfriend, Ruth (Jessica Henwick), however, poses an entirely different problem altogether. She represents a level of happiness, of contentment, that Becket never imagined possible, at least not without his family’s billions. The Redfellow body count on Becket’s ledger, though, makes it difficult, if not impossible, to root for Becket to succeed, at least not without some form of comeuppance for his misdeeds.

Julia’s recurring presence in Becket’s life, initially desired, then rejected by Becket, provides How to Make a Killing with both a femme fatale analog and a narrative wild card. For all of his admittedly slipshod planning and execution (a script-based issue, no doubt), Becket repeatedly underestimates Julia, her intelligence, and her cunning. She just might be his amoral equal, and in the Ford’s version of cosmic justice, the instrument for both Becket’s downfall and possibly, his salvation.

Like Kind Hearts and Coronets, How to Make a Killing unfolds as a series of flashbacks, beginning closer to the end of Becket’s story as he sits in a jail cell, sharing the events leading to his incarceration with a befuddled priest. Simultaneously, a clock on the wall conspicuously ticks down to the end. As a framing device, the flashback structure undercuts more than a few narrative-driven surprises, but what it subtracts from audience enjoyment, it re-adds in the final, ironic moments.

With broadly drawn, borderline-caricature characters (especially the Redfellow clan), an anti-rich theme (deserved, if a bit tired), and a sociopath for a protagonist, How to Make a Killing will leave some moviegoers frustrated, if not outright alienated from the eventual outcome. Its larger problem exists on a different level, though: the satire remains obvious, surface-level, and ultimately, too reductive, the humor too obvious and predictable, and its themes shrug-worthy.

Powell’s engaging performance as the charmingly sociopathic Becket, along with a game cast led by Qualley and Henwick delivering noteworthy work, certainly helps elevate How to Make a Killing into watchable territory. After it's all said and done, How to Make a Killing will be remembered, if it's remembered at all, as nothing more than a footnote on Horniman and Kind Hearts and Coronets’ respective Wiki pages.

How to Make a Killing opens Friday, February 16, only in movie theaters, via A24 Films.

How to Make a Killing

Director(s)

- Franck Dubosc

Writer(s)

- Franck Dubosc

- Sarah Kaminsky

Cast

- Franck Dubosc

- Laure Calamy

- Benoît Poelvoorde

Kind Hearts and Coronets

Director(s)

- Robert Hamer

Writer(s)

- Roy Horniman

- Robert Hamer

- John Dighton

Cast

- Dennis Price

- Alec Guinness

- Valerie Hobson

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.