100 NIGHTS OF HERO Review: Storytelling as a Spell of Resistance

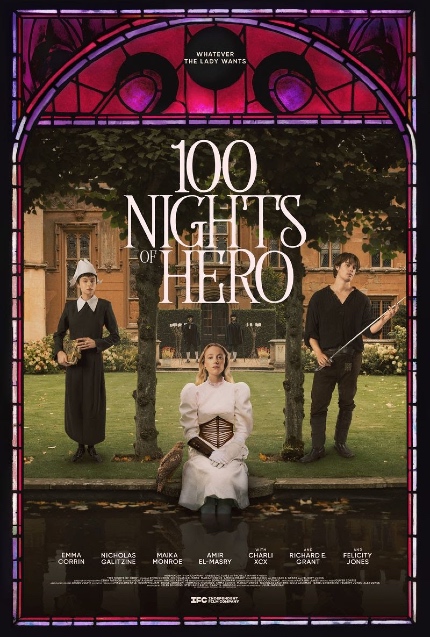

Emma Corrin, Nicholas Galitzine, and Maika Monroe star in Julia Jackman’s romantic, queer fantasy film.

For those who have yet to read One Thousand and One Nights, 100 Nights of Hero is by no means an inaccessible point of entry, as it draws primarily on the spirit and structure of the source material rather than retelling its stories. Serving as the closing film of this year's BFI London Film Festival, the film stages a compelling chemistry within an obscure triangular relationship.

The story unfolds in a medieval-like world ruled by the "Birdman" (Richard E. Grant) and other members of an enigmatic fraternity. Noblewoman Cherry (Maika Monroe) is forced into marriage with Jerome, the owner of the castle. Yet, in a cruel irony, her seemingly impotent husband never touches his bride, leaving the marriage unconsummated. This failure provokes the rulers' displeasure: should Cherry fail to conceive within 100 nights, her life will be in peril.

In the meantime, the arrival of Lord Manfred (Nicholas Galitzine), an unsolicited guest, shears off Jerome's ego and conceit. He secretly strikes a wager with Manfred: if Manfred succeeds in seducing Cherry within 100 nights, he promises to hand the castle over to him. Jerome then makes an excuse to run a business errand away from the hinterland for a few days and asks Manfred to take care of his new wife. In response to Manfred's flirtatious, invasive manner, Cherry and her maid, Hero (Emma Corrin), devise a counterstrategy. Hero will narrate a story to Manfred every time Cherry feels queasy, deliberately derailing his plan.

Corrin, who rose to international prominence for her portrayal of Princess Diana in Netflix's The Crown, occupies a perfectly calibrated mediating role within this web of entangled intimacies. As the storyteller, she carries the burden of narration and sustains the film's narrative structure.

Galitzine, meanwhile, has in recent years gravitated toward roles that explore unconventional forms of intimacy -- from the British prince who falls in love with the son of the U.S. President in Red, White & Royal Blue to the age-gap romance with a divorced single mother in The Idea of You. Here, his performance as a casual stranger attempting to seduce the taken wife is equally alluring and sultry.

Notably, Hero's storytelling is completed with such an interregnum incurred by the brief absence of sovereignty. The fictions she spreads not only delay the time shared with an "unauthorised" presence (namely, Manfred) but also allow tacit desire to proliferate throughout the space of the castle.

Storytelling, as an assertion of discourse power, can function both as an instrument of suppression for the powerful and as a spell of resistance for the powerless. It can be weaponised by Jerome as a pretext for violence, or reclaimed by Cherry as a tool of self-protection. For the latter, it performs as a means by which the oppressed break up with patriarchy and monarchy alike.

Nevertheless, what makes the film remarkable is its playful use of a double entendre. Although Hero is female, the true "hero" is not the heroine, but the story itself -- HERO as narrative force. Jackman deftly weaves together desire and abstinence, temptation and loyalty, within a landscape shaped by power struggles.

It conjures an atmosphere that is at once seductive and perilous: a moment of power vacancy in which rival forces eye the next of skin with tentative scheme. This is embodied, for instance, in Manfred's display of sculpted masculinity after the hunt, and his nightly, solitary howls of sexual frustration, caught between discipline and desire.

As a production made squarely for and by women -- from its director to its casting -- its feminist orientation is unambiguous. When women gain education and thereby slip beyond male control, they are branded as witches to be hunted. Hero, speaking from lived experience, re-narrates the episode of 'Rosa the Cunning' (featuring an impressive cameo by British pop singer Charli XCX). In her version of the tale, the women boxed into a corner do not submit to brute force; instead, under male coercion and abuse, they assert their subjectivity through a final leap into the void.

Within this masculinist contest, Jackman further incorporates a lesbian queer thread. Cherry, an ostensibly pure and virginal figure, comes to understand sexual desire through her intimate contact with Hero, an additional act of resistance against dominant cultural norms in mainstream society. Ultimately, 100 Nights of Hero departs from the tale 'The Dancing Stone' only to return to its narrative origin, creating a self-enfolding structure in which stories within stories interlock.

By bridging fiction and reality, the work not only liberates characters trapped on the page, but permits its feminist ethos to give birth, in turn, to queer subjectivities -- an achievement as elegant as it is exhilarating.

The film is newly available via various Video On Demand platforms, via Independent Film Company.

100 Nights of Hero

Director(s)

- Julia Jackman

Writer(s)

- Isabel Greenberg

- Julia Jackman

Cast

- Emma Corrin

- Nicholas Galitzine

- Richard E. Grant