KILLER OF SHEEP Blu-ray Review: The Future in a Handful of Concrete Dust

When most people think of American cinema of the 1970s, they focus on New Hollywood, the era of brash independent cinema that blew the roof off the old studio system and offered a more grimy, realistic, intimate look across a larger swatch of American life. That life, however, was still mostly white, and there was a small but growing rise of filmmakers who still were looking to make their voices, and the lives of their own people, known.

One such filmmaker is Charles Burnett, and a film that remained elusive but key to understanding that too long forgotten movement, is Killer of Sheep. Made in 1973 as Burnett's UCLA film school final thesis, it had only limited release in 1978 (Burnett had not secured music rights for many of the songs in the film), only finally screening at festivals some years later (wining the Critic's Award at Berlin Film Festival in 1981), it finally received its first general release some 30 years later. And now, one of the great films of American independent cinema, has both a blu-ray and a 4K from Criterion.

Killer of Sheep follows some days in the life of Stan, a slaughterhouse worker; his family; and residents of the Watts neighbourhood of Los Angeles, in the early 1970s. Not too many years after local riots against police brutality, Burnett chronicles the work, the play, the joy, sorrow, the quiet (and not so quiet) desperation and small moments of contentment found among the Black American working class.

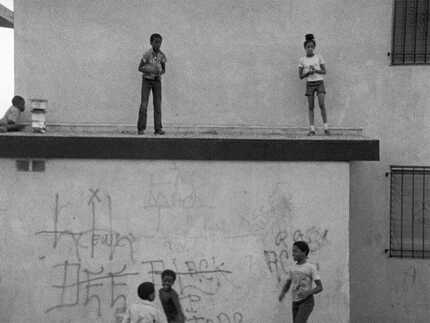

The film begins with children's voices singing a lullaby; but when an image appears, it's the face of another child, sad and perhaps a little scared, as his father is speaking to him sternly about how he needs to be there for his brother. A group of children playing at war with small concrete rocks and slabs of disused wood in some abandoned lot. It's through children that we're first introduced to this world, and the black and white, 16mm, 1:33:1 aspect ratio, all make this world feel intimate and tight, despite its sometimes open spaces. At once protected, yet behaving with reckless abandon within this confinement, the world of children who, far too early, perhaps are forced to keep one eye on adulthood.

And what of that adult world? There is Stan (Henry Gayle Sanders), the titular character: like many working class men of this era, he works long hours at a job he doesn't like, leaving him little time or money to enjoy his life, his wife, his children. The American dream that he (and so many others) were promised, as he's slowly realizing, was a lie, and especially as a Black man in America, there is little chance to get out of this drudgery of life, leaving him to constantly search for more means just to get by into something of a reasonable life. On one side, he's confronted by people in his life who turn to less than legal ways to stay alive; on the other, a scene in which a white store owner makes it very clear that a job she offers would come with some sexual harassment, reminds Stan of the rocks and hard places between which he is squeezed.

The people of Stan's community, such as his friend Bracy (Charles Bracy) and Eugene (Eugene Cherry), finds themselves in similar situations, with varying reactions. Some try to hustle, some try to find joy; some resign themselves to this quiet desperation. One man finds himself injured by a tire iron to the head, sleeping on someone's living room floor. A neighbour announces a pregnancy, to rounds of joy from her women neighbours. An army man, having stepped out on his girlfriend one too many times, finds himself trying to avoid the end of her gun. One scene has Stan and a friend carrying an extremely heavy motor down two flights of stairs, only to have it fall off the back of the truck.

His wife (she's not given a name, played by Kaycee Moore) has her own desperation, but unlike Stan, she is not quiet about it; at least not all the time. She knows what she needs from this life, and speaks with strength and poetry, refusing to back down in the face of the daily defeats, both major and minor. She wants love and safety for her children, the love of her husband, to know and touch the world without fear or reservation, and she brings this possibility with every encounter. In a scene with Stan sitting on his front steps, two men of the 'hood on either side, it's she who interrupts this composition to confront then men's failure to step out of gendered stereotypes, to tell them (with dialogue improvised by Moore) what it truly means to be a man.

His wife (she's not given a name, played by Kaycee Moore) has her own desperation, but unlike Stan, she is not quiet about it; at least not all the time. She knows what she needs from this life, and speaks with strength and poetry, refusing to back down in the face of the daily defeats, both major and minor. She wants love and safety for her children, the love of her husband, to know and touch the world without fear or reservation, and she brings this possibility with every encounter. In a scene with Stan sitting on his front steps, two men of the 'hood on either side, it's she who interrupts this composition to confront then men's failure to step out of gendered stereotypes, to tell them (with dialogue improvised by Moore) what it truly means to be a man.

Another beautiful scene, showing Burnett's unique eye for portrait-like composition with people and in a place not normally afforded such care and beauty, shows Stan and his wife slow-dancing to 'Bitter Earth' sung by Dinah Washington. Stan's hesitation to fully engage, despite what he longs for; his wife's refusal to give up what she needs, results in a moment filled with such love and longing, in the filtered light through the curtain, carries a tremendous weight. One of Burnett's strengths as a filmmaker is giving these seemingly small moments this great weight, moments when we are not flies on the wall, but as much a part of the scene as the characters, showing us that we must proverbially drink from their well.

The near-square aspect brings across the tightness of this world, that the place has some strange unnatural border that prevents people like Stan from truly escaping. Even shots which show more area, like a long streetscape or one of the many vacant lots on which the children play, feel empty. But within this emptiness, there is still possibility, as Stan's wide alludes to. The black-and-white photography, which might have been done out of necessity, ends up emphasizing that the lives of these people are far from this monotone. There might be moments of loss, as Stan feels every day in his job, bringing sheep to slaughter; but he also has a tender moment with his daughter; the children leap over chasms in reverie.

Killer of Sheep is not just a classic of American cinema, but a quietly revolutionary work: one that brought a grassroots realism to cinema, a frank and caring look at the lives of Black Americans that had never been seen in the cinema before. It's a film of pain, laughter, and poetry, and one that encourages multiple viewings.

One of the reasons it took so long to become available for home viewing, was the poor quality of the original negative. Luckily, hard work by the restoration team have made a stunning transfer for both Blu-ray and 4K, as well as work on restoring the audio. It looks just as fine in its grainy black and white as it did when the first audience would have watched it nearly 50 years ago.

The disc includes two of Burnett's first shorts. Several People is something of a prelude or a practice run of Killer of Sheep, with some of the same actors, largely improvising dialogue, but giving Burnett a feel for the camera, the people he wanted to film, and the style by which to film them. The Horse is a beautiful and elegaic story of a white family, waiting for their Black worker to arrive and shoot a horse, who is beloved by the worker's son, William. Burnett is furthering refining his documentary style combined with some improvised dialogue and characters that move within a specific time and place.

Interviews with Burnett and his main actor Sanders, help flesh out the story of the film, how it was created, its inspiration in how Burnett wanted to show the real lives of Black Americans, to counter the on-screen images of the more popular Blaxploitation cinema of the 1970s. Sanders had ended up in Los Angeles because he had hoped to sell a novel, and ending up in acting almost by accident. Filmmaker Barry Jenkins contributes his perspective on the influence of Killer of Sheep on the Black filmmaking community in America for the next several decades, with the focus on a kind of neo-realism influenced by European cinema, and not yet replicated in American, until Burnett's work.

Clips from an interview with Burnett highlight the LA Rebellion Oral History Project, for those (like myself) who might be unfamiliar with the film movement and its importance in film history. But perhaps the highlight of the film extras, besides A Horse, is a documentary in which actor and director Robert Townsend (The Warriors, Hollywood Shuffle) accompanies Burnett on a shooting location tour around Watts, discussing how the neighbourhood has and hasn't changed, how he ended up shooting certain scenes, how the film was embraced at European festivals but Burnett had no offers for further work once he returned to the USA for a long time. Lucky for us, he did go to make more excellent films.

Danielle Amir Jackson's beautiful essay delves a little further into the history of the Watts neighbourhood, discusses Burnett's use of children, the importance of the music, how the film is the blues put to screen. And the place of the film as part of the LA Rebellion, the counter to the New Hollywood that allowed for a wider look at different working classes in America.

Killer of Sheep will be released by The Criterion Collection on May 23rd.

Killer of Sheep

Director(s)

- Charles Burnett

Writer(s)

- Charles Burnett

Cast

- Henry G. Sanders

- Kaycee Moore

- Charles Bracy