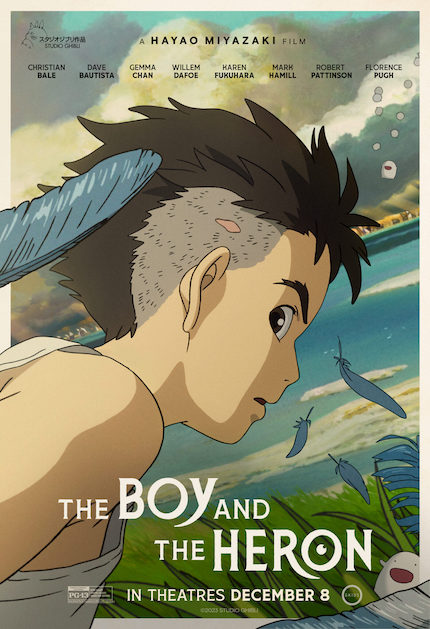

THE BOY AND THE HERON Review: Culmination of a Life's Work

From the opening air raid sirens and fiery infernos of World War II Tokyo bombings to the bucolic countryside house and its magical surroundings, Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli have come full circle in its 40-year history of animated mastery.

Lovers of the studio and its particular blend of high fantasy and domestic adjustment will find The Boy And The Heron delivers in some ways exactly what fans want: a retrospective tour of images and ideas many know and love. The film does not break much in the way of new ground, but gently reminds you of the early duo of My Neighbour Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies, an unlikely pair of masterworks that burst Ghibli into global adoration in the 1980s.

To my initial surprise, The Boy And The Heron feels weirdly rushed and sloppy in its narrative, as if the audience could (and should) fill in the blanks from their enjoyment of Ghibli and Miyazaki (and his late partner Isao Takahata’s) extensive body of work. This in no way diminishes the utmost care, patience and craft of what is realised here on screen.

Is it worth the ten year wait since the maestro’s previous film, The Wind Rises? Absolutely. Is it a boldly original masterpiece? Not quite. Does it serve a purpose in the tradition of Ghibli’s lore and mystique? Resoundingly, yes.

Young Mahito runs desperately through the streets as Tokyo blazes, crimson shimmer and terror. His mother, a nurse, is consumed by the hellfire of war as her hospital block is reduced to ashes. His widowed father, Shoichi, moves them out to the country to a large house. It is styled in a western Victorian design in the back, with a Japanese veranda and entrance in the front.

Shoichi marries his dead wife’s sister who, in alarmingly short order, is pregnant with child. As his father becomes absent, putting in a lot of overtime work to oversee a wartime factory making aircraft hatches (which look a fair bit like the Ohmu shells from Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind) his step-mother suffers in bed through morning sickness, and Mahito is left adrift in strange new circumstances; where he is looked after by the gaggle of house grannies. Miyazaki certainly has a knack for designing elderly women, both sweet and strange.

For nearly the first hour of the film, Mahito is drawn into the household politics of scarcity, where cigarettes or canned beef are luxuries during the war. A certain kind of domestic freedom can be bought by trafficking these goods brought in by his father's position. This privilege does Mahito no favours at his new school, where his classmates are resentful and unwelcoming. The school is more of a co-op labour camp (for the good of the nation in its time of struggle) than a place of reading, writing and arithmetic.

Aggressively bullied in the working fields, one day on the way home, Mahito inflicts a grievous injury to himself to avoid returning. While he is recovering from his own self-harm in this strange old house, he has several encounters with the local heron, first flying onto the porch, then snooping, to full blown pestering Mahito to discover the ancient tower on the edge of the property.

At first the heron serves the story as a belligerent form of Lewis Carroll’s white rabbit from Alice In Wonderland. Much time and care is given to the movement, design, and evolution to the eponymous bird over the course of the film. Just watching how it positions its body to enter a small window is splendid indeed.

At first the heron serves the story as a belligerent form of Lewis Carroll’s white rabbit from Alice In Wonderland. Much time and care is given to the movement, design, and evolution to the eponymous bird over the course of the film. Just watching how it positions its body to enter a small window is splendid indeed.

Eventually Mahito, and one of the feistier of the Grannies, Kiriko, get sucked into a Howl’s Moving Castle-like portal to another world, a place of vast oceans, with endless fields of grass. There is an aggressive army of pelicans who feed on cute marshmallow like Warawara spirits (visual echoes of the infant-like Kodama wood spirits from Princess Mononoke).

Mahito finds an early guide in the form of a seafaring woman, akin to Spirited Away’s bathhouse straight-backed veteran, Lin. She guides him through economic and ecological system of this vast curious underworld.

What other animated film but a Ghibli one would have an extended scene of gutting and carving an gigantic hideous fish with professional efficiency and care? The buyers of the fish are also a pleasure, translucent men of colour and shadow with straw hats and casual posture. One can get (and will) lost in the design of such details, which are the true pleasure of The Boy And The Heron. Rewatches will be rewarded by detail over plotting.

Mahito is also aided in his journey by Himi, a powerful maiden of fire and avatar for his deceased mother. At one point, she sets a fine table of bread and jam (echoes of domestic comforts of The Secret World of Arrietty), but she mostly ushers him through the complex energies of this land of the dead, a magical construct of a mysterious ancestor of theirs, where souls come and go to be reincarnated. It is home to an army of buff and militant parakeets.

One can barely begin to note or highlight all the visual elements in the film: the care of crafting an arrow by cutting and gluing a feather fletching with sticky rice-paste, to make an arrow fly true; pulling a sail to harness the endless and powerful wind on the sea; the gentle fall of curtains, an exquisite show in and of itself, as a character slips into a taboo chamber; the grannies represented as carved wooden dolls in the alternate world; a stoney Castle In The Sky that crackles with neural energy, a master architect holding the construct together with children’s blocks.

Miyazaki demonstrates how our imagination builds coping mechanisms. Even if they are transient and confusing, we can later emerge from the cocoon to (hopefully) find our place in the world. To embed ourselves into a what feels like a ‘proper’ place is not surrender, but rather a graceful sacrifice towards the mechanisms of nature.

The more I watch Ghibli films (The Boy And The Heron both tickled and cemented this feeling), the more I come to understand Ghibli tells stories of people, either young or old —sometimes both— who attempt to understand complex and strange human and environmental ecosystems. The stories are less about an antagonist to be bested, and more about internal and external integration, finding a glimmer of understanding that leads towards the satisfaction of knowing where you fit.

To that end, I feel that I may possibly understand what is being done with this film. It is likely the last (but hopefully not) from Miyazaki. Knowing what he does and how he does it, The Boy And The Heron is both a validation of the studio’s traditions and personal ancestries, and a culmination of a life’s work, realized and positioned in the exactly the right place.

Review originally published during the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2023. The film opens Friday, November 8, in movie theatres nationwide via GKIDS Films. Visit the official site for more information.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.