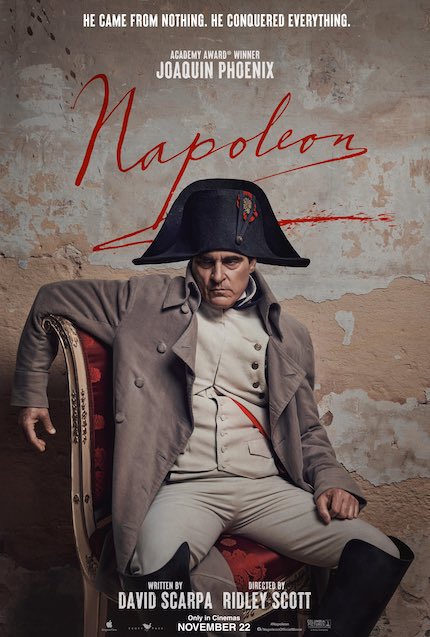

NAPOLEON Review: Ridley Scott's Engrossing, Enthralling Anti-Epic

Joaquin Phoenix, Vanessa Kirby and director Ridley Scott star.

At an age when most filmmakers have long since exited the scene or shuffled off this mortal coil, the 85-year-old Ridley Scott (The Last Duel, Kingdom of Heaven, Gladiator) shows little sign of slowing down, let alone retiring to peaceful quietude in rural France, where he owns and operates vineyards.

He’s completed roughly one-half of his long-mooted Gladiator sequel, aptly titled Gladiator 2, while a vaguely described Western tantalizingly awaits as his next project once he completes work on the Gladiator sequel. Other, still unspecified projects are more than likely in the planning or development stage.

Until then, self-described cineastes, fans of historical epics, and general audiences will have to content themselves with Scott’s latest film, Napoleon, an epic biography of the ex-military leader turned emperor — and tyrant — who ruled France and significant parts of Europe at the beginning of the 19th century. A figure of obsessive fascination for academic scholars, pop-culture critics, and filmmakers alike (Stanley Kubrick spent the better part of a decade on a Napoleon project of his own) since he died in exile on St. Helena, Napoleon, played by Oscar winner Joaquin Phoenix, remains a frustratingly perplexing, contradictory figure.

A military strategist without equal, gifted with the ability to lead hundreds of thousands of soldiers into battle (and almost certain death), but also a psychologically astute politician capable of bending, twisting, and manipulating the ever-shifting, chaotic politics of post-revolutionary France, he was, at least in Scott’s uneven telling, a socially awkward, petulant man-child almost fatally obsessed with Joséphine de Beauharnais (Vanessa Kirby), his future wife (and ex-wife) and onetime empress. Nothing, not even war-making and expanding France’s empire into territories colonized by the other so-called Great Powers, can stop Napoleon, learning of his wife’s public infidelity, from leaving his command in Egypt and returning to France.

Scott continually contrasts Napoleon’s unhealthy fixation with Joséphine to the title character’s rapid ascent from a relatively unknown captain in the French Army to emperor of the French Empire, with stops along the way for intermediate commands and accompanying levels of power. When Napoleon isn’t obsessing over Joséphine and later, providing an heir to continue his bloodline, he’s planning and leading one military campaign after another.

Scott deliberately skips explaining the various European alliances that repeatedly put Napoleon into conflict with the British Empire, the Russian monarchy, and among others, the Austro-Hungarian Empire over the better part of two decades, though he does give what audiences explicitly expect from a film about Napoleon, the terrible spectacle of war, of soldiers, cavalry, and artillery thrown into conflict on battlefields across Europe.

While Scott has already talked about releasing a longer, four-hour cut of Napoleon, the two-and-a-half-hour theatrical version doesn’t shortchange audiences spectacle-wise. Scott highlights three battles, Toulon, where a fresh-faced captain by the name of Napoleon Bonaparte, won a life-changing battle; Austerlitz, where Napoleon’s tactical and strategic genius reached its apotheosis; and Waterloo, Napoleon’s last battle and his most crushing defeat.

Waterloo sent Napoleon into a second and final exile. Scott often takes a god-eye-view of the battles as thousands of soldiers clash while Napoleon, ensconced high above the battles on high terrain, directs different segments of his army like a modern-day gamemaster with head nods and shoulder shrugs.

Scott’s fascination lies not just in the grand set pieces a film like Napoleon affords a filmmaker of his skill, talent, and experience, but perhaps as a form of autobiography. As leaders of vast, often unwieldy productions, marshaling hundreds, sometimes thousands, filmmakers and military-generals-turned-emperors might have more in common than at first appears, especially for directors of Scott's age who’ve worked across decades and changing working conditions (Blade Runner, for example, was notorious for its long hours and unhappy crew).

Of course, a simpler explanation also presents itself. For a filmmaker like Scott, who toiled in commercials before making his feature-length debut in 1977 with The Duellists, the inherent power of the image, of translating what he sees in his mind into the spectacle onscreen, has compelled him to make one film after another.

Whatever the underlying reason, there was never any doubt a master craftsman on Scott's level would deliver on the epic scale and scope a subject like Napoleon demands. Scott’s decision to counter-balance Napoleon’s rise and fall as a military and political leader with Napoleon’s relationship with Joséphine, however, certainly creates, if not outright doubt, then at least some confusion as to the "why" behind the decision, especially given Phoenix’s idiosyncratic performance as Napoleon.

Sometimes painfully shy and clumsy, often speaking as if history’s always taking note offscreen, occasionally terrifying (especially once he becomes France’s de facto king), Phoenix’s eccentric performance crosses — deliberately or not — into cringe-comedy and even camp.

Even as Joséphine’s motives for remaining at Napoleon’s side remain murky, sometimes driven by malleable situational ethics, sometimes by emotional need, and often by the wealth, power, and prestige of her privileged position as Napoleon’s wife, Kirby gives a more relatable, less alienating performance. Her Joséphine, buffeted by political forces she can’t control, let alone fully understand, emerges as a nuanced, three-dimensional character.

Scott’s decision to depict Joséphine’s foundational life experiences (imprisonment during the Reign of Terror, survival by any means necessary, up to and including sex work, after her release) makes her if not entirely sympathetic, then far more than the emperor who divorced her because she couldn’t bear him an heir.

Napoleon opens Wednesday, November 22, only in movie theaters, via Sony Pictures.