MICHAEL HANEKE: TRILOGY Review: Cooly Unsettling

Criterion collects Michael Haneke's first features, which form a rewardingly challenging triptych.

To what degree Michael Haneke is out to impact/affect his viewers as opposed to straight-up emotionally scarring them will forever be a point of debate.

Or perhaps it won’t, thanks in part to this three-film run of the controversial and highly regarded Austrian auteur’s earliest feature films.

By the time one’s experienced even just a portion of the films and features contained in Criterion’s Michael Haneke: Trilogy set, certain hardline assumptions may well be challenged. The titles -- The Seventh Continent (1989), Benny’s Video (1992), and 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994) -- show that while Haneke’s been uncompromising and blunt since his filmmaking beginnings (and this is a collection of his narrative feature beginnings), it’s all been in the service of bolstering a baseline humanist sympathy.

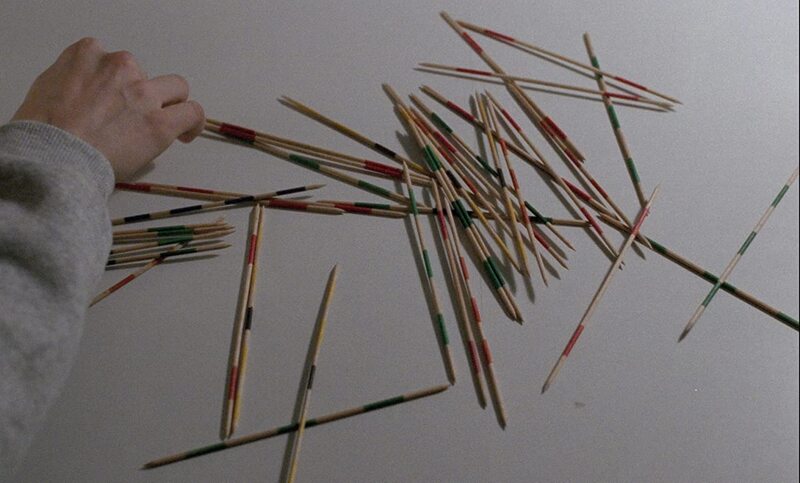

“The best way to go about this is systematically.” That close approximation of dialogue spoken by one of Michael Haneke’s main characters in 1989’s The Seventh Continent is nothing if not apropos to the film itself. Haneke, for his theatrical film debut, finds his way inside the detached and fragmented mind behind tragic actions taken.

Of course, we don’t know where all these quiet shots of riding complacently through an automatic car wash, vast breakfast table spreads, and kid artwork in the making are headed, but their shared austerity tells us plenty. This much is clear: Their seventh continent can’t be a good place.

The Seventh Continent, while remaining laser focused on the three family members (played by Dieter Berner, Birgit Doll, and Leni Tanzer), is broken up into many seperate chunks by abrupt cuts to black. These cuts seem to get a little longer every time, presumably preparing us for whichever will turn out to be the last one, the end, the permanent fade out.

The film’s title, referencing a plotted move to Australia from the family’s hometown of Linz, is an elusive monicker that somehow works for the material, regardless of anyone’s actual travel plans. The family members are cagey with the world and with one another, though in the case of the latter, there is a thorough unspoken understanding. Fatalism abounds through every moment of The Seventh Continent’s 104 minutes.

Already, I feel as though I’ve said too much about The Seventh Continent’s story. What more can and should safely be said is that the three leads are excellent, particularly young Leni Tanzer, who plays the dejected couple’s doom-addled daughter. When she fakes going blind at school, her internalized reaction to it almost convinces us that she’s being honest. Her mother, in quizzing her about it, assures her she won’t hurt her. The very next inquiry results in the mom slapping her daughter across the face, followed by a hard cut to black.

Then there is the increasingly unsettling Benny’s Video, from 1992. Benny, played by Arno Frisch, who expertly walks the line of being both sympathetic and scary, is presented as a seemingly ordinary 15-year-old boy, though one with a myriad of video recording, editing, and playback equipment in his room. It’s his hobby, and one that his disconnected upper-middle class parents are happy to facilitate.

With this video equipment, he can run videotapes backwards and forwards at varying speeds, allowing Benny to freeze-frame the exact moment he’s fixated on. Unbeknownst to mom and dad (Angela Winkler and Ulrich Mühe), it is moments of killing. His current fascination lies with footage of a pig’s demise, carried out in part by his parents on a farm they have a stake in. The footage of the pig getting a captive bolt pistol to the noggin (all real, beware) is the very first thing we see in Benny’s Video.

When the madness momentarily kicks in, we see it on a screen. But then, isn’t that true of any movie depicting madness or anything else? Technically speaking, then, it’s a screen -- Benny’s monitor, displaying the live recording -- on our screen. Such a connection is quite likely intentional on Haneke’s behalf as he probes the persuasive power of the recorded image in a most uncomfortable way.

Before long, Benny’s Video is evoking both Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin and Haneke’s own later Funny Games films. This precursor to both doesn’t quite land in their realms of capital-D Disturbing, though it absolutely has its moments. Later in the story, the captive bolt pistol makes a comeback. Before there was Anton Chigurh, there was young Benny.

Then, murder. As an anemic stream of blood is disposed of down a bathroom drain, one can’t help but think about Hitchcock’s Psycho, and how it had to be restrained when it came to its depictions of the aftermath of its central murder. Haneke, however, isn’t having it. He makes his point (one of many) by then immediately going to the victim in the other room: lifeless, shattered, and involuntarily spilling of saccharine sinew and pulp.

As upsetting as the (probably) impromptu murder itself is, it’s the subsequent combination of Benny’s extreme sociopathic disconnect and the complicit willingness of others to cover for him that really makes Benny’s Video stick. With its confluence of disaffected youth, then-emerging video technology, class entitlement, and even a touch of unappetizing anti-meat signaling in the wake of the pig slaughter, Haneke’s deliberately distancing movie leaves its mark.

The third and final Haneke feature of Criterion’s Trilogy set is also the most experimental. Fragmentary to its core with raw formality overriding conventional characterization is 1994’s 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance.

Grimy grout and unmopped grease and food remnants adorn the many workaday kitchen surfaces and living quarters that reoccur throughout. Common clutter is everywhere, easily selling the intended observational “reality” of this piecemeal drama. The characters are unmade-up, almost always bundled in unglamorous knit clothes and winter coats. The moments are broken up by intrusive cuts to black.

Somewhere amid the continuous presentations of the ultra-mundanities of contemporary life in Vienna lurks a stark look at the death impulse that exists in all of humanity. On TV, air strikes threaten helpless populations of strife-ridden cities and nations. Sometimes, the TVs are just on in the background, blaring whatever concocted content the broadcasters are pumping into homes.

In a prolonged single-shot scene, an old man’s at-home telephone conversation with his loved one feels tonally led by the content on the ignored tube. As the blaring shows seamlessly shift from images of niceties to wartime unrest, the man’s chat veers from encouragement to hurtful criticism. Haneke, by burying the TV in the frame and obscuring much of its screen, leaves such details for the viewer to either notice or not.

The intermittent news clips, filmed by Haneke straight off a TV monitor -- adjusted to 24 frames per second to avoid the flicker that would’ve otherwise occurred circa 1994 -- of civil and political unrests punctuate the numerous more controversial sequences of the aptly if overly literally titled 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance.

One harrowing TV report of a baby rushed to a hospital because of shrapnel gives way to a story about whether Michael Jackson, then on trial, was lying or not. The shift from the dire to the tabloidy is not only jarring, it’s revolting. And then later, it’s repeated in a permutated form. The many news segments of horrendous Israeli-Palestinian conflict are all too reflective of today’s headlines, cementing that Haneke, back in the day, was indeed onto something.

Throughout the film’s overall harsh documentary-style observational aesthetic, the film does have reoccurring characters played by actors, each moving through their own stories. One is an unhoused kid (Gabriel Cosmin Urdes) who’s illegally crossed into the country and proceeds to steal image-based things like comic books and a camera.

Another is an irritable young man (Lukas Miko) who’s gun-running side hustle eats into his mechanical ping pong playing and computer game development. Sebastian Stan, of all people, makes his brief film debut as a kid goofing around on the underground train platform. He claims he hated every minute of making the movie.

*****

If there’s a unifying thematic shared by this icy triptych, Haneke himself claims it to be the complex notions of guilt that his characters internalize. He speaks of this at greater length in the 2005 interview excerpt found on the Blu-ray disc devoted to Benny’s Video.

That disc also has some narrated deleted scenes as well as a 2018 interview with the now-grown lead Arno Frisch, who happily reflects on the big break that this part brought him as an actor. For someone who was prominent in both Benny’s Video and the original Funny Games, Frisch seems terrifically good natured and well adjusted!

I kid about that, but the fact of the matter is that same sentiment also seems to apply to Haneke himself, who’s jovial chattiness and openness in his ‘05 interviews is genuinely surprising in the best way. In his third of the three 2005 interview supplements (one grouped with each title), Haneke states: “In film, we often pretend that we know everything. ‘The character is this.’ A character is never just this. It’s also that. And all these contradictory ‘alsos’ are often contradictory. That’s what makes life so rich and also irritating.”

He goes on to say that imbuing his films with such contradictions is all in the interest of creating an illusion of the richness of life. He considers his films -- all his films, not just these three -- to be expressions of a desire for a better world.

In keeping with Criterion’s recent turn towards simpler and more compact packaging, the three discs comprising Michael Haneke: Trilogy come in a single-disc-sized package. While this helps in terms of many collectors’ problems with lack of shelf space, it also utilizes a half-stacked method of making the discs fit inside. There is simply no outward grandiosity apparent with this type of packaging for a set such as this. Undeniably, something has been lost.

The packaging artwork by Eric Skillman succeeds. It almost couldn’t be more minimalist: a small grid of stills from each title in a field of light grey. Yet, this is wholly appropriate for the contents within.

The dominant shade of grey reads as detatched, cool to the touch, remote, even depressive. It’s deceptively simple, but fully apropos. Interestingly, the printed essay in the included booklet is by novelist John Wray, whose novels often deal with displaced characters in strife-ridden real-world areas.

Besides an insightful new video interview with film historian Alexander Horwath, the set also contains Michael H. Profession: Director, a feature-length documentary by Yves Montmayeur about Haneke’s career featuring interviews with the filmmaker as well as actors Juliette Binoche, Isabelle Huppert, and Jean-Louis Trintignant. Mostly though, it’s Haneke himself pontificating at the interviewer’s behest.

The 2013 profile goes behind the scenes of many of his films, including Amour, The White Ribbon, Code Unknown, The Piano Teacher, and finally, the original Funny Games. It’s a terrific look at the very unique director, though newcomers beware: spoilers for all of those films and others abound throughout.

It’s very important to Haneke that his work not merely reflect the violence of the world; mainstream cinema, he says, ordinarily does so but renders it “consumable,” imbuing insidious actions with acceptability as to be entertaining, but in so doing, drive viewers to want the opposite in life. And whatever his methods, he can get away with it, because as he says, “In cinema, the viewer is the director’s victim.”

Here’s Criterion’s official listing of special features found in the Michael Haneke: Trilogy set:

• High-definition digital masters, supervised by director Michael Haneke, with uncompressed monaural soundtracks

• New interview with actor Arno Frisch

• New interview with film historian Alexander Horwath

• Interviews from 2005 with Haneke

• Documentary about Haneke’s career featuring interviews with Haneke and actors Juliette Binoche, Isabelle Huppert, and Jean-Louis Trintignant

• Deleted scenes from Benny’s Video

• Trailers

• New English subtitle translations

• PLUS: An essay by novelist John Wray

The Seventh Continent

Director(s)

- Michael Haneke

Writer(s)

- Michael Haneke

- Johanna Teicht

Cast

- Birgit Doll

- Dieter Berner

- Leni Tanzer

Benny's Video

Director(s)

- Michael Haneke

Writer(s)

- Michael Haneke

Cast

- Arno Frisch

- Angela Winkler

- Ulrich Mühe