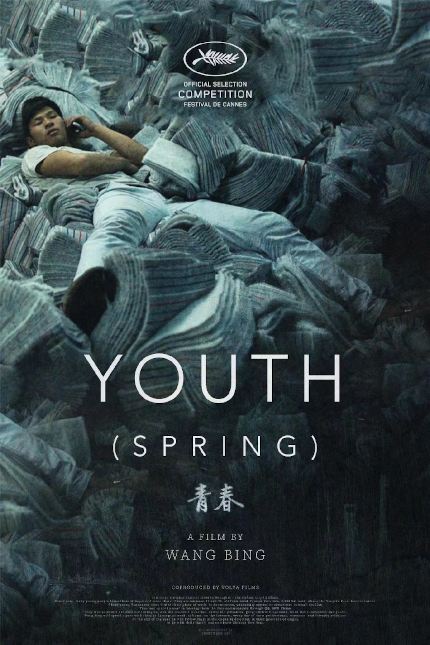

Cannes 2023 Review: YOUTH (SPRING), Chronicle of China's Working Class Youth

Chinese director Wang Bing makes his Cannes Competition debut with a stunning, expansive work about China's youth working in the country's garment industry.

Chinese director Wang Bing is one of the biggest names today in the world of documentary filmmaking.

His monumental nine-hour film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2002) is regarded as one of the greatest films of the 21st century, non-fiction or otherwise. Since its release, his profile has only increased in prestige.

It is then no surprise that he finds himself in Competition at Cannes this year with Youth (Spring), only the third documentary given this honor after 2004’s Fahrenheit 9/11 and 2008’s Waltz with Bashir. Given that the reigning champions of the other two major European film festivals are docs -- All the Beauty and the Bloodshed won Venice in September 2022 and On the Adamant won Berlin in February 2023 -- perhaps Cannes realized it needed to pick up the slack when it came to non-fiction programming.

Youth was filmed for over five years, pre-COVID, from 2014 to 2019, 150 km from Shanghai in Zhili, the heart of the Chinese garment industry. Here, every year, seasonal workers, typically aged late teens to late 20s, come from other rural areas of China for demanding work, operating sewing machines for the mass production of clothes, children’s clothes in the case of Youth (Spring).

The work is back-breaking. The average day ranges from 8 AM to 11 PM, the conditions are dingy, and the pay is below what we might consider minimum wages in North America. These young people typically work here from July to January, staying in dormitories right above their sweatshop, and produce anywhere from 3,000 to 5,000 pieces of clothing per worker every month. Youth is the chronicle of their life and times and Spring represents only the first part of an intended trilogy or 3-part part project, the totality of which will span over nine hours.

In terms of filmmaking, Wang Bing’s aesthetic is perhaps closest to American documentary legend Fredrick Wiseman. There is no voiceover employed, nor is there any use of archival footage or pictures, or graphics of any kind on the screen. Youth only consists of completely unvarnished footage of these young people doing their work and living their lives.

Structurally, the film consists of about nine segments spread over its length of three and a half hours, with each segment roughly 20 minutes in length. Each segment is based in a different sweatshop, and we meet a different cast of young people in each.

What Wang Bing has managed to capture here with his observational style is stunning and remarkable. There is hard work in these images but also so much life and desire and just plain teeming youth.

We see the young workers, male and female, competing about who can sow the fastest, and who can produce the maximum number of pieces. We see scenes of their life outside of work too, in their dormitory, fooling around, hanging out with friends, getting take-out and food, throwing a surprise birthday party, going to a cafe, and so forth.

These are not lives of abject misery, as one might be led to believe, despite the working and living conditions, which would surely violate regulations in North America. But China is a different culture and operates on its own terms. What’s reassuring and relatable is that here too the young people dream and desire, flirt, fall in love and hook up, and look for means to have perhaps a better life than currently available.

The format of the filming pushes the documentary medium. Almost all the footage included here is filmed in extremely long, unbroken takes running multiple minutes on end on average. It truly gives a spontaneous, life-like feel to the entire film.

We can only guess regarding the filming methods employed but clearly, the participants, once they agreed to be filmed, were so comfortable in front of the camera that they could be their uninhibited, unfiltered, candid, unguarded selves. Maybe it is a feat of extraordinary curation, but the scenes included are teeming with such life that, given their long-take nature, the audience might wonder if these are staged by actors. The participants are all very disciplined, and only on a couple of occasions does someone look at the camera or seem aware of it or break the proverbial fourth wall.

Of all the scenes included, the most stirring are the ones where the young people get together and discuss means of securing higher wages by raising the average for everyone. You can see the seeds of activism or unionization blooming naturally in a subjugated population of young, able-bodied workers who are not getting their due from the management.

These scenes result in lengthy negotiations and collective bargaining with the managers, which are almost thrilling in the sense of the very real conflict and stakes they present. It is thus a bummer to see the young workers often come in on the losing side of these arguments, as they are gaslit and manipulated by the managers into accepting lower wages because they realize the one truth: in a country of 1.4 billion people, they are all ultimately expendable and replaceable. Even so, there is tremendous vitality in the scenes selected and presented to the audience and it is very easy to get engrossed in the lives of these real people.

If there is one downside to Wang Bing’s approach, it is that Youth (Spring) overstays its welcome due to its repetition. As mentioned previously, we move from sweatshop to sweatshop, spending about 20 minutes at each, before going over to a different cast of characters. To a large degree, this is an assembly-line business, so the adage 'you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all,' holds true.

The scenes shown to us at different sweatshops differ in minor details but the overall experience is the same, the insight gleaned is identical and by the sixth or seventh time, tedium begins to set in. It is a fair question to ask: wouldn’t five or six segments have been sufficient rather than eight or nine? Sure, Wang Bing filmed 2600 hours of footage, but isn’t the fundamental point of documentary filmmaking, exercising discretion and judgement in what to include?

Even so, Youth (Spring) is a remarkably involving and revealing look at the youth of China, making of their lives what they can, grappling with their prospects, and trying their hand at adulting. It is never not poignant seeing young people be carefree and careless before the rest of their life has caught up with them.

Youth (Spring) premiered in Competetion at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.