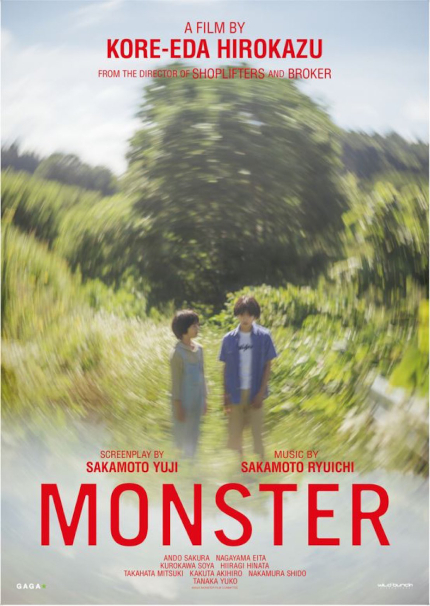

Cannes 2023 Review: MONSTER, Complex Chronology, Brave Message

Kore-eda Hirokazu directed a impactful drama with genre trappings.

Given the title of Japanese master Kore-eda Hirokazu’s latest film, Monster, and the sinister, gripping first 40 minutes, you might be forgiven for thinking you are watching a high-brow possessed zombie-child movie. After all, isn’t this how most Hollywood horror films unfold, with a relatively placid but increasingly discomforting first act where the tension builds in anticipation of the crazy shenanigans to come?

Monster begins much the same way. Saori (Sakura Ando), a widowed young single mother, is raising her 11-year-old son Minato (Soya Kurokawa) with wholesome joy and loving care. Out of the blue he starts behaving in a bizarre manner.

His shoe goes missing, he has mud in his water bottle, he has a gas lighter in his possession, he comes home with a bloody ear and filthy clothes, and roams the marshes alone at night. He has appalling mood swings and claims that he has a pig’s brain instead of a human one. At one point he jumps out of his mother’s moving car.

Is he possessed? Has something happened? It turns out a young teacher at school, Mr. Hori (Eita Nagayama), is mentally and physically assaulting him, leading to some of his erratic behavior. Saori, primed with a parent's outrage, barges in at his school and raises a firestorm, demanding answers and threatening consequences for her son’s poor treatment. But is everything as it seems? At the 40-minute mark, just as an American horror film would bring its horror elements to the forefront, Monster fades to black.

What follows isn’t any forward descent into genre conventions but a backward lurch in time as we revisit the entire first 40 minutes, this time from the accused teacher's perspective. And after that has played out, we double back once again, this time seeing the events from the accusing child’s perspective. As you can imagine, each time an entirely different reality emerges about what has transpired.

Atonement publicized itself with the tagline "The truth can only be imagined". It would suitably serve Monster as well. Through this Rashomon-like structural gambit of conflicting perspectives, Kore-eda shows us how a fresh vantage point can result in diametrically opposite conclusions about similar sets of events.

Rather than repeating itself, the film actually expands outwards with each re-telling, adding new characters, new incidents, and new layers of detail and meaning than we have previously seen before. Everyone has an angle. Everyone has their reasons. Everyone is the hero of their own life story. All this is doubly true, as the questions about what's going on with Minato multiply rather than subside and the situation becomes murkier by the minute until the final act sheds some light on what’s actually up.

We'll treat this revelation as a secret, though other critics have notably chosen to disclose what's going on in a cavalier, nonchalant manner. It isn't necessarily hard to guess but the film is clearly constructed to hide that fact from the viewers and the characters in the story and have it gradually emerge as a cathartic epiphany that contextualizes everything we’ve seen. It gives Monster its weight and gravitas. We wouldn’t want viewers to be robbed of that process of discovery.

Kore-eda hit the big time with his last Japanese film Shoplifters after it won him the Palme D’or in 2018 and got him an Academy Award nomination for Best International film. Monster should continue that trajectory, very much in line for a big prize (maybe even the biggest prize again) and certain to be a strong awards contender in the International Film category when it opens stateside later this year.

Kore-eda is directing for the first time since 1995 from a screenplay he did not write. The screenplay is credited to veteran Korean TV writer Yuji Sakamoto and to a degree is both the film’s greatest strength and weakness. The script allows Kore-eda to arrive at a still controversial subject (at least in the US) obliquely -- from a somewhat genre-based approach -- that might make it more palatable to audiences. It’s definitely an unusual way of narrating a story of this kind and contextualizes the disastrous consequences of trying to put singular kids into square pegs.

But the script also proves to be too much of a good thing. It is definitely over-written and over-wrought, to the extent that every last thing that happens on screen, even the most incidental or minor detail or chance word uttered, serves a purpose and is explained twice or thrice over. Conservation of detail is to be appreciated but when you see a story this thoroughly worked out, you begin to see its design and start noticing its construction and precision and intricacy rather than getting lost in the characters. Monster is too over-engineered by half.

Even so, Kore-eda’s direction is typically strong and he does his best to present this rather complicated story as naturalistically as possible on the screen. He is known for his work with actors and the performances across the board are typically strong.

Sakura Ando as the steely single mom is absolutely tremendous, building upon her lauded work in Shoplifters. She carries the first act of the film and her fury at the poor treatment of her child is stirring. Child actor Soya Kurokawa is in some ways the de facto lead of the film and pulls off a remarkably complicated part.

Eita Nagayama as the embattled teacher Mr. Hori is good but tends towards overacting in some of his pivotal breakdown moments. Hinata Hiiragi as Yori, the other young boy tied up in the entire affair, and Akihiro Tsunoda as the principal of Minato’s school, are also excellent. Together with the central trio, they form the quintet of leading characters.

Technically, the film is well-assembled. Considerable editing dexterity is needed to assemble a complex storyline with several scenes being staged several times from different angles to represent different perspectives. Besides the staging complexity, Kore-eda also impresses with two mini action-setpieces. One is a blaze at a brothel which opens the film. The second is the climatic thunderstorm which leaves the fate of key characters in doubt.

Oscar-winning composer Ryuichi Sakamoto’s (The Last Emperor) original score is sparse but impactful in its haunting melancholy. He passed away after completing work on this film. Monster is dedicated to his memory.

Monster is a worthy film that arthouse audiences should enjoy. It might even find favor with a broader audience because of its genre trappings, tricky structural dynamics, and the impactful message at the heart of the story.

Monster premiered In Competetion at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.